BBV behavioural programme ‘Safe at heart’

Safety is at the heart of everything the High Speed Two (HS2) programme does. This paper describes the behaviour safety programme that was developed by Balfour Beatty VINCI (BBV) – the Main Works Civil Contractor for the northern section of HS2 Phase One – to drive a safety culture for all staff, contractors, and the supply chain across the contract.

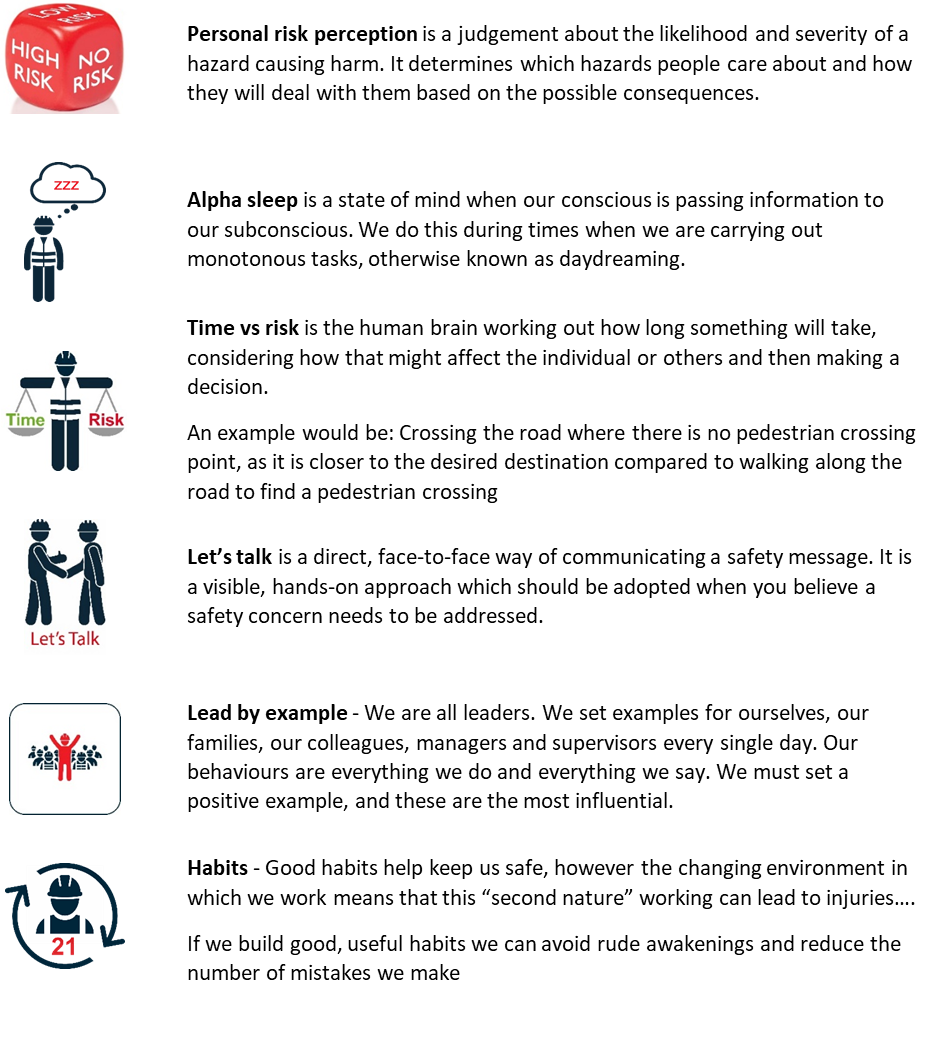

The programme was developed around six behavioural currencies (building on that originally created by Network Rail) which relate to effective behaviour management and the skills needed to explain the importance of managing workplace risks and their consequences: a) Time v Risk, b) Lead by example, c) Daydreaming, d) Personal risk perception, e) Habit, and f) Let’s Talk. It was built for the project by the workforce and delivered by BBV peer trainers including trainers from the supply chain.

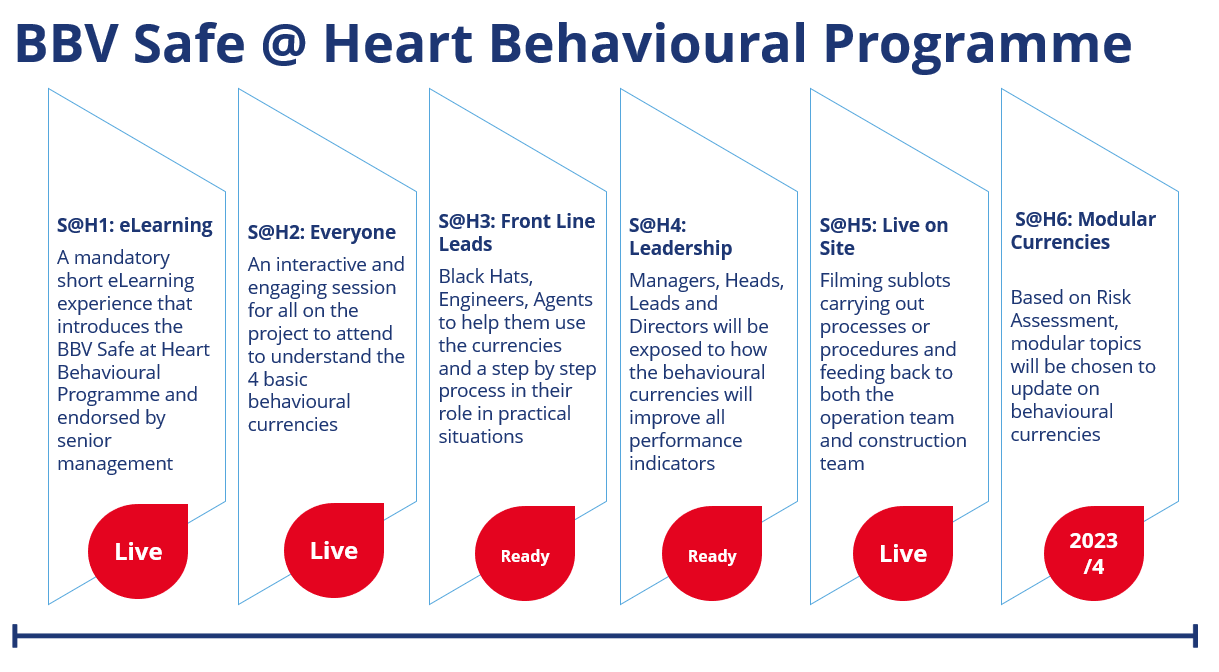

The programme consists of six modules: a) eLearning, b) everyone, c) front line leads, d) leadership, e) Live on site (which involves filming on site and feedback to the team), and finally f) a project specific module based on significant risk of a sub-lot.

75% of the 4500 strong workforce have been trained on the BBV behaviour programme Safe at Heart in 8 months and will be ramping up to 10,000 over the next 12 months. In the first six months BBV has found significant improvement across all five leading indicators (observations, site team inspections, SHE inspections & audit, health screening, and employee consultation) and the Accident Frequency Rate.

This paper shares best practice on establishing a lasting behavioural safety programme and will be of interest to future projects developing a behavioural safety programme.

Introduction

The Integrated Project Team for the northern section of High Speed Two (HS2) Phase One – Balfour Beatty VINCI (BBV) – developed and launched an employee and supply chain led behavioural programme called “Safe at Heart” in April 2022. A previous behavioural programme had not been effective and was not tailored to the unique requirements of BBV. This was corroborated by a health and safety survey conducted in February 2022 which identified that the operatives believed there was no behavioural programme on BBV and that one was needed.

This paper describes the behaviour safety programme that was developed by BBV to drive a safety culture for all staff, contractors and the supply chain across the contract. BBV at its peak will have a workforce of 10,000 people.

Background and Industry Context

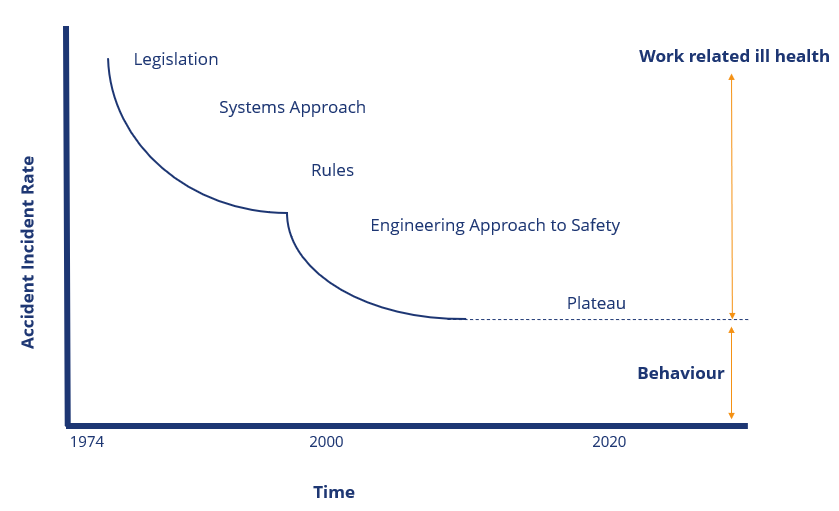

There were 30 fatal injuries to construction workers in 2021/22 and an estimated 78,000 work-related ill health where 53% were musculoskeletal disorders[1]. An important point is the word ‘estimated’ as the long latency of many work-related diseases makes it difficult to link a serious illness to an individual that is diagnosed, treated, and then potentially dies from their condition relating to work being one of them.

From the same report above[1] it is clear that for every one safety related fatality, there are many more construction workers lose their lives from a disease incurred because of their work. Work-related ill health does not need to be fatal and by demonstrating the right behaviours and correct choices will reduce work related ill health significantly. Behaviour is the only way the gap between safety and health related deaths will get smaller. Abandoning current working practices, looking again at the levels of risk, changes to processes and use of technological advancements will bring change. At BBV Ill-health due to work, in whatever form that it may occur, is not acceptable.

The illustration 1 shows the theory behind leadership by example and engagement.

Safety behaviour at work is a critical part of the management of health and safety because behaviour turns systems and procedures into reality. Systems on their own do not ensure successful health and safety management, as the level of success is determined by how organisations use their systems. Donald and Young[2] suggest that little remains to improve on in terms of physical conditions and considering that approximately 80-90% of accidents are caused by unsafe acts, further construction safety improvement is hardly expected to improve without more concentration on the reduction or elimination of unsafe acts.

As outlined in research by Mearns & Yul (2009), different cultural backgrounds may influence behaviours on site and could potentially cause cultural clashes leading to unsafe systems and acts, although management itself has been considered a more important determinate of behaviour at work than national culture[3].

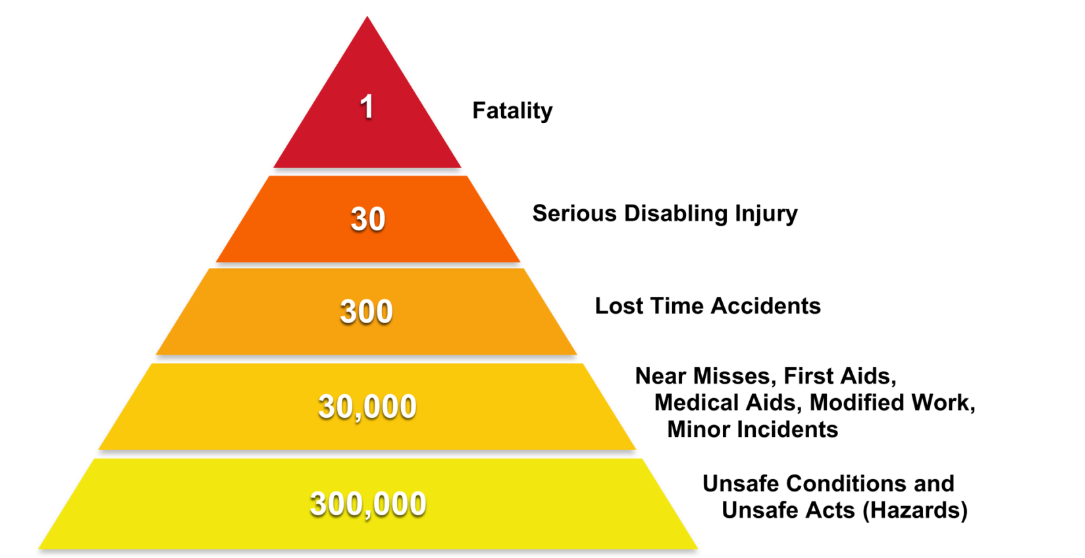

Behavioural training has become popular in the safety field as there is evidence that a significant proportion of accidents and incidents are caused by unsafe behaviours.[4], Employees can often behave unsafely because they have never been injured before while doing their job in an unsafe way: “I’ve done this job for 30 years and never had an accident” being a familiar comment. This may well be true, but the potential for an accident is never far away and is illustrated in the accident triangle in Figure 1.

Figure 2 represents the ratio between at-risk behaviours, near-miss events, and injuries by severity. Heinrich’s[5] and Bird’s[6] findings about the relation between different categories of accidents are widely accepted in safety-related domains, although the ratio may vary between sectors

Carter & Smith[7] state that general hazard/risk perception of construction workers has been found to be far from ideal. They analysed method statements from construction projects and found only 6.7% managed to identify all of the hazards that should have been identified based on current knowledge. Some of the barriers identified included subjective risk perception, operatives’ and management behaviour, and their decision-making. This was taken into consideration when developing the BBV behaviour programme Safe at Heart, to rely on the importance of human factors, the currencies and the reduction of unsafe acts in the construction population. Fleming and Lardner[8] concluded that human behaviour is a contributing factor in approximately 80% of work-related accidents and injuries sustained. Behavioural based safety is a process which in turn reduces unsafe behaviours that can lead to incidents occurring in the workplace. Fang et al[9] and Jiang et al[10] state that an effective strategy to enhance the safety management and the safe performance of construction projects is to prevent and control unsafe behaviours of workers.

The behaviour related approach to dealing with occupational health and safety (OHS) has been shown to be valuable and as a result many construction organisations employ this method to achieve robust safety management systems. In reducing error and influencing behaviour, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) states that an estimated 80% of workplace injuries can be attributed, either wholly or in part, to the actions of people. Behavioural safety aims to limit the kind of employee actions or omissions that add to this statistic. Lagging indicators such as accident rate and fatalities have been used to measure safety performance[11]. These indicators have been widely criticised for their reactive nature and inability to provide advanced warning for accidents[12]. Therefore, leading indicators such as safety behaviours have been developed and utilised to measure safety performance more effectively[13]. As a result, construction organisations typically give their behaviour-based safety programmes different names and pride themselves for achieving high safety standards because of the aspects of behavioural safety that they focus on. However, it is unclear as to which specific aspects of such programmes are the keys to success and which are of secondary importance to improving OHS. Griffin and Neal[14] proposed safety compliance and safety participation as subdimensions of safety behaviour. Safety compliance is defined as following rules and is the core of safety activities. Safety participation is conceptualised as behaviours that may not directly contribute to workplace safety but help develop an environment that promotes safety.

Behavioural currency techniques are widely used on construction safety programmes and were first published in Network Rail’s ‘Making a Difference’ behavioural programme. They are intended to empower anyone and everyone in any department to discuss, support, and offer advice on matters affecting their occupational health and safety. It is recognised that operations vary widely on HS2, requiring a variety of methods of discussion and suitable involvement of the workforce. Everyone from the supply chain, contractors, employees, workforce, and external companies are stimulated to support, cooperate, and engage, fostering a culture of continuous improvement, where behaviour improvements and safe behaviours are encouraged, rewarded, recognised and successful improvements are celebrated. Hence the behavioural currencies were used as the basis for the BBV programme.

Approach

The BBV behaviour programme on HS2 is based on the concept, ‘You can’t change behaviour until you know the behaviour you need to change’. BBV has found this is secured through respect and cooperation of everyone involved. First-hand involvement in the actual conditions of work at every level means those managers and employees build and encourage working environments that are open and honest, identifies potential problems and can proactively manage the risks associated with their work and provide appropriate solutions. Lingard & Rowlinson[15] states that unsafe behaviours are in the individual’s control and within the scope of supervisors and management to control effectively. Langford et al.[4] states, that supervisors knowingly ignore unsafe acts due to time pressure set by agreed programs. These references informed the development of the story boards and the focus that BBV needed to encourage participants when building the BBV Safe at Heart behaviour modules 3 and

Identifying the need

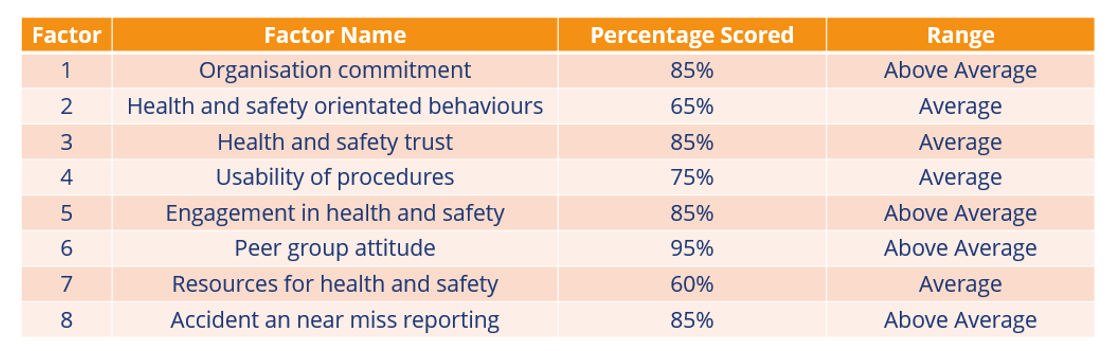

BBV administered two main surveys – the first a Human Resources employee survey December 2021 and the second the HSE safety climate survey in February 2022. Both surveys measured health and safety climate against compliance and participation, the results of which are shown in Figure 3. Figure 4 is an amalgamation of the 2022 HS2 HSE Climate survey results. The survey was undertaken prior to the BBV Safe at Heart behaviour programme conception. Factor 2 – health and safety-oriented behaviours was one of the lowest scores and identified the need for a behavioural programme to be created.

Based on the outcome of the surveys and the feedback from other sources e.g., accident, incident and observation requests, the Director of SSWHE wanted a behaviour programme that could meet several requirements for the BBV Joint Venture. The challenges included, “What was the behaviour BBV needed to change, why and how?”

Developing the programme

At the time of starting in April 2022 the BBV population was 1,000 personnel moving to 4,500 personnel by the end of 2022, and a forecasted 10,000 personnel by the end of 2023. Of this population a number were in transit or short bursts spending only 5 to 6 months on the project. This is important because a transient workforce will bring their own culture and behaviour and as an organisation, there is not enough time to coach and embed a positive behaviour change before they move on.

The behavioural strategy objective was to teach the six behavioural currencies which relate to effective behaviour management and the skills needed to explain the importance of managing workplace risks and their consequences. By providing workplace environments to allow employees to feel comfortable to make the right choice, take their time and speak up.

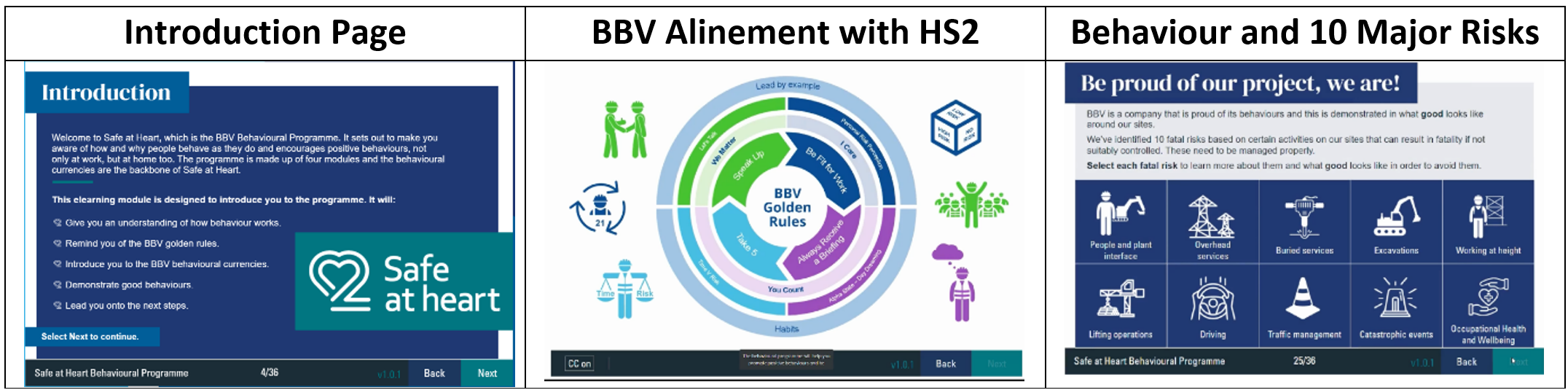

These six behavioural currencies (originally created by Network Rail) are commonly used by construction companies: a) Time v Risk, b) Lead by example, c) Daydreaming, d) Personal risk perception, e) Habit, and f) Let’s Talk. Figure 4 shows the six BBV behavioural currencies.

The BBV Safe at Heart behavioural programme is aimed to support, promote, and develop a clear and practical understanding of how to achieve a positive health and safety culture through an effective behaviour programme. The early success of the programme is measured through feedback of participants and reviewing leading and lagging indicators twice a year. Measures include Observations, Site team inspections, SHE inspections & audit, Health screening, and Employee consultation, and one lagging indicator, Accident Frequency Rate.

The BBV Safe at Heart behaviour programme’s philosophy is to work collaboratively with managers, employees, contractors, and supply chain, to ensure we promote the best behaviour on the project. Exploring people’s habits, attuites, and actions to help improve, coach, and support daily behaviour and reduce unsafe acts on site.

To develop the BBV behaviour programme Safe at Heart several discussions took place with the workforce at all levels and a common list of improvements emerged including:

- Keep it simple and interactive

- Avoid one behaviour program fits all

- Delivered by peer trainers

- Involve all departments

- Use the experience of the workforce

- Bite-size and interactive learning

- Target behaviours to site risk

BBV brainstormed the challenges and developed a presentation for the first modules and outline the programme. These were presented to the director of SSWHE and Senior Leaders who supported the programme and added an extra e-learning module to be developed for new starters so three modules became four. Later two additional modules were added and hence six modules form the current programme as shown in figure 5. These modules (5 & 6) were added to give the programme longevity. Module 5 consists of ongoing filming of sites carrying out processes or procedures and feeding back behaviours demonstrated to both the operation team and construction team. Module 6 consists of 100 topics based on risk assessment; modular topics are chosen to update behavioural currencies on all types of media.

BBV behaviour programme Safe at Heart modules 1 to 6 underwent several stages of research and development that included:

- Development of the 6 modules

- Review of the Balfour Beatty “Making safety personal”.

- Review of feedback from the project teams and supply chain workforce via employee and HSE surveys

- Workshops at all levels and final review

- Unveiled to the operational Heads of safety and the wider H&S Team.

- Senior Management approval and eLearning

Developing the modules

It is important during the development of a safety behavioural programme that the target audience is taken into consideration. For example, if the audience is young or old the trainer’s approach must be capable of retaining their interest and their illustrative examples used must be within their experience. The trainer must be aware of external influences such as levels of literacy and numeracy peer pressures and preconception of safety issues and use them to their advantage. Presentations using videos, PowerPoint, experience discussions, breakout groups and questions need to be related to the material to be covered and the experience of the candidates. Use of handouts or websites and any additional reading can offer further support. The course environment in terms of size, layout, lighting, ambiance, heating, and lunch is all part of the overall training experience.

The author developed the storybooks for each of the modules and these were further developed with the BBV Engagement Manager together with additional BBV working teams. When developing the storybooks, the lessons from the two surveys and the interviews with the operatives were always kept in mind. At this point a workshop was set up with the subcontractors who form part of the BBV integrated project team construction family, to gain their expertise and buy in to the behavioural programme. All members of the working groups contributed to the final development of the modules and the pilot date and time was set to deliver module 2.

Developing Safe at Heart 1: When taking into consideration the BBV Safe at Heart 1 behaviour eLearning, workforce learning behaviours also play a role in the overall success of any e-learning implementation. Therefore, the introduction had to provide the purpose and the context for workers to deal with the content and information. The activities had to be active and engaging and provide opportunities for reflection and articulation. Figure 6 includes extracts of the eLearning module.

Something that is stressed at the start of all the 2-hour modules is that this is a safe environment. Experience tells us that people are more likely to speak up, share examples and scenarios if they are not going to be embarrassed, penalised, or chastised. A success of the programme is offering of a safe environment for people to share. Each example, story or scenario that is raised by the audience, or in some case the facilitators, is used to further explain, emphasis and embedded the meaning of 6 currencies and how they work in their lives.

The course content works with this basic process:

- Ask the question

- Gain examples from the room

- Discuss the theory

- Play the game

- Watch the video then Summarise.

Each section, although subliminal in its existence, provides opportunity for audience interaction and engagement, and to learn from each other’s experience, and the facilitator can link the course material to the examples provided by the audience.

Developing Safe at Heart 2: The Safe at Heart 2 module really works when encouraging an open and honest discussion and providing that safe environment. When asked, ‘What is personal risk perception, and can you provide examples inside or outside of work?’, the audience are usually very quick to share their story about themselves or others.

The facilitator stimulates conversation about how and why people behaved the way they did in the scenario raised and then look at it through the Safe at heart lens. This method of sharing has several benefits, it encourages others to speak up and share their stories, (leading by example) and it makes the session unique, bespoke, and personal. This is much likelier to be remembered by the participants and will be spoken about long after the session has finished. Behaviour coaches and peer trainers who work on site confirmed this when discussing the currencies and training on their sublot.

Rolling out the programme

After several iterations, the eLearning for module 1 was ready to be launched in September 2022. The storybook for module 3 and module 4 was being prepared by December 2022 for delivery in March 2023.

After listening to BBV employees feedback a plan on a page was developed. This looked at a short, medium, and long-term plan developing early resources and requirements to achieve some early goals. See Table 1.

| Stage | Start Date | Period | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research & development time | December 2021 & Feb 2022 | 2 Months | Feedback & Surveys analysed, and relevant improvements incorporated into presentations |

| Sat Launch module 2 | April 2022 | 1 Month | Commence delivery of 2 module to 8 sublots 4000 employees and supported by project Senior Managers |

| Safe at Heart Modules | Module 2 May 2022

Module 1 eLearning Sep 2022 Module 3 Dec 2022 Module 4 Dec 2022 Module 5 Dec 2022 Module 6 Jan 2023 | 80% by end Dec 2022

Start Sept 2022 Start Module 3 Jan 2023 Start Module 4 March 2023 Start Module 5 Dec 2022 To start end of 2023 | Identify and train Peer Trainers on.

|

| Supervision and Management modules | Supervisors 80% by August 2023

Managers 90% by December 2023 |

1 Year 2023 | Commence delivery of Safe at Heart 3 & 4 Supervision and Management modules by the Engagement Manager with support and assistance of supply chain and engagement team. |

| Safe at Heart 5 Module | At Lease 1 visit to each sublot | Programme for each sublot | Modules to ensure consistent standard of delivery across all Sublots |

| Safe at Heart 6 Module Additional modules | November 2023 | Develop Modules 2 Month | Delivered by Peer Trainers and measured as part of sublots KPI’s. Develop presentation template for further modules |

It became apparent that peer trainers were going to be required to be able to deliver Safe at Heart module 2 to 4,120 people and in May 2022 the process of training peer trainers started. By September the BBV Engagement team had trained over 110 peer trainers, 11 for each sublot with an aim to reach 70% of the population by December 2022.

Continuous Improvement

BBV aims over time with the behaviour programme to affect real and lasting change in behaviour avoiding the safety plateau and driving accident and incident statistics down. Along with peer trainers BBV will deliver continuous improvements and develop the behavioural program further equipping participants with tools and techniques that they can use as soon as they get back to their sites. The programme through the behavioural currencies promotes respect and trust for one another, improves working as a team and planning together. Focuses on effective communication, ensures accessible and approachable management who can create the environment for the currencies to work. BBV’s experience means that we understand the real needs for behavioural training and what our participants want. The training is customised to the modules, and materials are developed in house to ensure quality and flexibility; written situations are brought to life through enjoyable practical exercises.

The following activities were identified for continued progression of the Safe at Heart 1 programme:

- Identify targeted campaigns/briefings by trending of project feedback, inspections, audits (internal & external) and VLT comments.

- Identify Safe at Heart Champions from project workforce and staff (Role: To support and underpin key messages as exemplars of behaviour. Assist Peer trainers in organisation / admin of training sessions etc)

- Sublots visits by Peer trainers (cross fertilisation)

- Peer Trainer Forum / support network to be set up to identify.

- opportunities for improvement of the programme/training

- review visual standards & share across the BBV sublots

- review specific high-risk issues

- Communication via; all types of media

- Surveys

Outcomes

BBV has identified five leading indicators, these include, Observations, Site team inspections, SHE inspections & audit, Health screening, and Employee consultation, and one lagging indicator – Accident Frequency Rate. To give early indicators of success halfway through the behaviour programme. See Table 2 below showing improvements in all measurements over the first six months.

| February 2022 (before the BBV behaviour programme) | Monthly Total | October 2022 (6 months after the BBV behaviour programme) | Monthly Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observations | 4410 | Observations | 8431 |

| Site Team Inspections | 69 | Site team Inspections | 189 |

| SHE Inspections & Audit | 92 | SHE Inspections & Audit | 195 |

| Health Screening | 44 | Health Screening | 74 |

| Employee consultation | 0 | Employee Consultation | 40 |

| Accident Frequency Rate | 0.11 | Accident Frequency Rate | 0.06 |

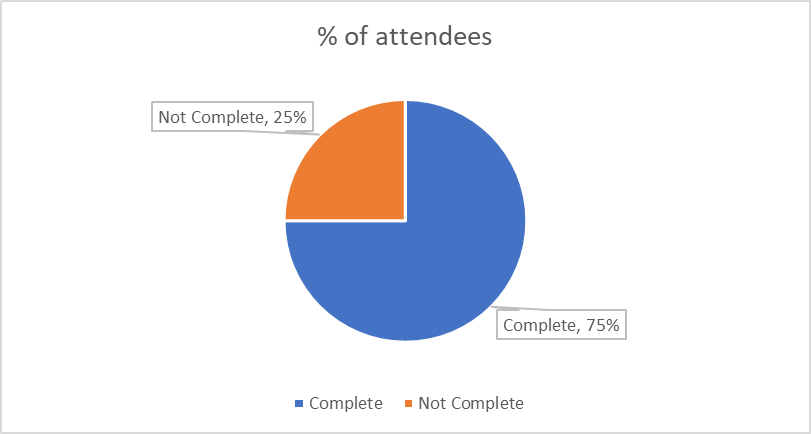

The programme is open to anyone and by the end of 2022 there were 4,120 people working on the project. In just 8 months 3,216 have attended BBV Safe at Heart module 2. This was made up of 343 BBV employees, 12 HS2 employees 2,861 Contactors, and Subcontractors (see figure 7)

After each BBV module 2, attendees are asked to populate a Microsoft attendance form via scanning a QR code. This method of digitally capturing information was adopted given the geographical nature of the project and the many sublots that BBV work across. Interested parties can quickly look at live data to see who has attended. At the bottom of the form is a series of feedback questions that the attendees are asked to populate. This feedback is used monitor the success of the module and provides people a way to suggest improvement ideas. Below is information taken from the feedback from.

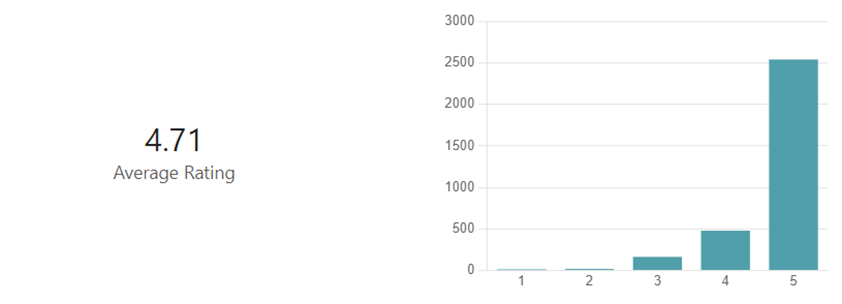

When asked to rate the course on a scale of 1 to 5, 1 not so good – 5 very good, 2,539 rated the course very good, and a further 479 rated it good. This equates to 93% of all attendees. (See figure 8)

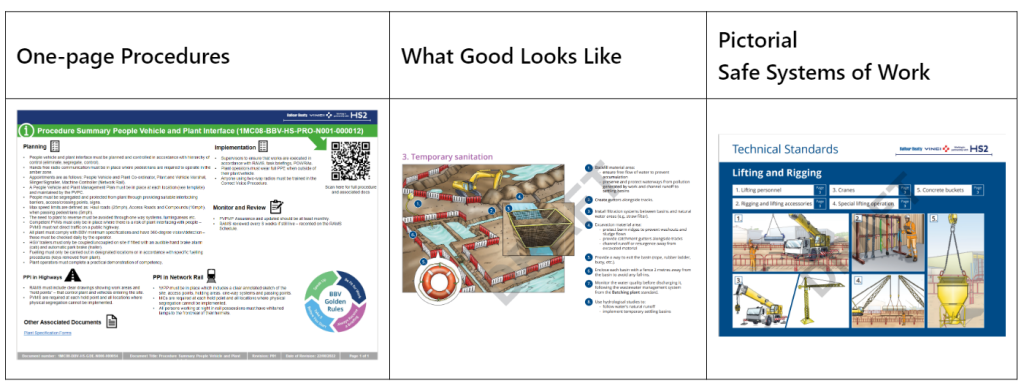

There is an opportunity for attendees to manually enter feedback in their own words as well as the scoring above. Completing this question is not mandatory however 1,242 attendees provided further feedback with the word ‘Good’ appearing in 504 of those entries, (see figure 9). The feedback is a reflection of the aspirations of the trainer and the interactive and engaging manner the modules are constructed and conducted.

Further analysis can be taken from the final feedback question. Would you recommend the session to others? This data is valuable in checking that the sessions is having the desired effects of engagement, interaction, and enjoyment. Of those who attended a Safe at heart 2, 99% would recommend the course to others, (see figure 10).

There is of course no immediate return on the changes that we make today. Today’s changes will only be realised in the decades to come and that is when we will learn how effective we have been. However, in this paper BBV has identified short term improvement measures (leading and lagging indicators) to ensure the programme is on the right track. BBV in collaboration with HS2 has a medium-term measure in the form of The Health and Safety climate survey tool. This is a tool to help BBV and the other joint ventures improve health and safety performance through employee involvement, sharing information, and measuring alongside other HS2’s joint venture companies.

To reduce accidents, incidents, and ill health creating working environments where the behaviour currencies are part of what BBV do is key. Using this programme we look after each other and speak up about our concerns, at all levels to deliver safer working environments knowing BBV will listen.

Learning and Recommendations

Involving contractors and the supply chain particularly helped improve small medium enterprises (SME) safety – And was embraced by the workforce, supply chain, and contractors. A small working group was set up to review the story board for the behaviour modules. It was represented by nine SME’s, one client, two BBV management and several of the BBV workforce. The group discussed the format and delivery of the modules and ensured the success of the programme. During this time several of the SME’s requested to adopt the BBV programme as they either did not have a behaviour programme, or the behavioural programme they were currently using had lost traction. . This was an important characteristic as research has shown that the small medium enterprises have less adequate control and arrangements for health and safety (13). The way this behavioural program worked is the involvement of the contractors and supply chain. Establishing the workshops and allocating responsibilities sharing resources and establishing a wide communication with all interested parties. This had to rely on trust between all parties a closer working relationship to share information. This was shown in the early part of peer training when a particular sublot was not performing in delivering the BBV Safe at Heart behaviour programme so one of the working group subcontractors offered their support and help. Setting a date and presented module 2, to 45 people in two days and to date that particular sublot is now one of the best performing.

More resources would have allowed quicker adoption – With more resources the program could’ve gone slightly better by starting all the modules at the same time focusing on management and supervisor’s modules first then the everybody module and then the e-learning as an annual refresher. This would have improved the working environment quicker to allow the adoption of the programme sooner.

Retention of Peer Trainers – Although 110 volunteered to become trainers to deliver module 2 only circa 50 trainers have found the time in their diaries to deliver sessions. Despite being advised before attending a train the trainer session the expectations and time needed to support in its roll out. A more robust explanation and easily understood forecast of the time required from each trainer to devote to module 2 may have given them the opportunity to decline the role. This would have allowed others across the sublots an opportunity to become trainers and may have led to a higher number of attendees attending the sessions in 2022.

Audit would support continuous improvement – BBV would have benefitted from an audit schedule to observe sublot-run module 2 sessions. This would have provided feedback both positive and opportunities for improvement, on how the session was delivered. The audit would also have identified those trainers that were unable to deliver session due to other commitments and an action plan could have been devised to mitigate.

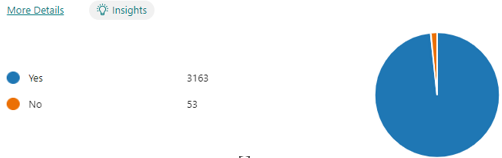

Engaging the supply chain has led to programme-wide safety improvements – The supply chain workshops have developed and managed several improvements in creating safe working environments on many of the sublots (See figure 11). Providing feedback on what they could support and help with and identifying improvements of how BBV could Improve has led to several general improvements and involvement in several wider workshops that include people plant interface, lifting, and working at height. Communication and feedback have vastly improved with 4,120 employees reporting 68000 safety observations in 2022 compared to 3,800 employees reporting 30,492 in 2021. The feedback on the observations focused on positive safety interventions and personal risk perception and a few of the other currencies.

Examples of the Improvements

Alignment of behavioural programme through the supply chain – One of BBV main supply chain partners used an alternative behavioural programme. After presenting BBV Safe at Heart to their Senior Health and Safety Manager in September of 2022 they were quick to recognise the simplicity of the BBV Safe at Heart programme and chose to adopt the roll out of it to further support the BBV ambitions. This ensured that the same messaging was being delivered and demonstrated the importance of BBV and its supply chain being aligned in the behaviour programme approach. All the top twenty HS2 contractors have adopted the BBV Safe at Heart behaviour programme, putting the eLearning on their training platforms and in some cases (Labour Only) delivering the training before operatives starting with BBV. The feedback from just a few who attended as you can see in Figure 12 below was positive.

Feedback from Attendees Safe at Heart

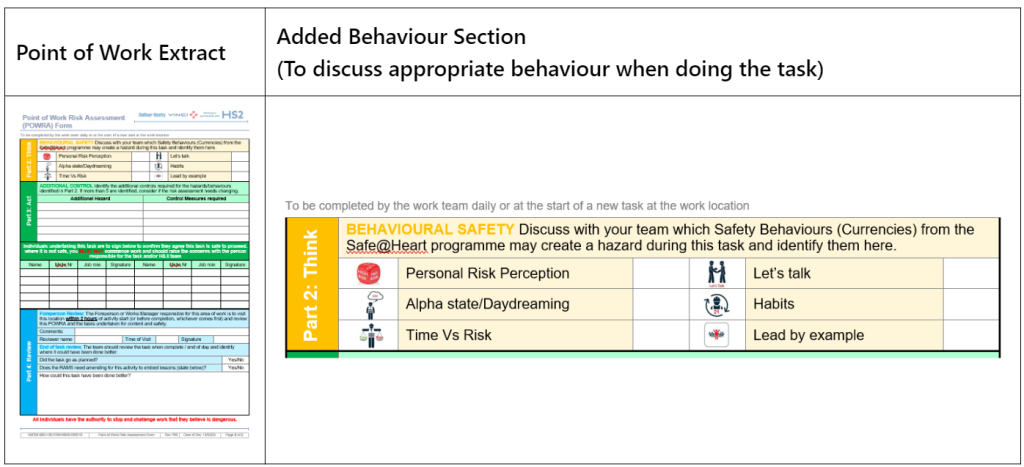

The Point of Work Risk Assessment Template has been reviewed and amended to now include a section where the end user assesses not only the working environment but considers what human factors could cause an issue for the activity being undertaken. The template is intuitive and prompts the user to think about the behavioural currencies and consider how to mitigate unwanted behaviours as figure 13 shows.

Point of Work Risk Assessment

Conclusion

The BBV Safe at Heart behaviour programme is about understanding the behaviour you need to change, this is achieved by giving more involvement to the individual, improving communication, participation, coaching, and engaging. The programme aims to encourage employees to make the right choices, improve their decision’s, and achieve the best outcomes by using the safety currencies.

It enables and coaches each person who can pass on the behavioural currencies and bring along others with them. Creating an environment that makes people feel, their values, attitudes, and perceptions with regards to safety matter to BBV and their views are appreciated in the workplace. By doing this more of the workforce will engage more frequently in safer behaviours and as a result fewer accidents, incidents and issues will occur.

Implementing a behaviour program in a construction environment is normally expensive and time consuming. Cost can easily escalate when you buy in consultants in and ask them to train your entire work force, the continuing cost of additional training or train the trainer and the development cost if you want to add additional modules or training. The programme is normally off-the-shelf and not tailored to your project therefore changes are always needed at additional costs. At a time when most clients encourage reducing costs and reducing completion times, BBV Safe at Heart behaviour programme, apart from the time training, is inexpensive and in its first eight months shows real results in supporting and developing, one page procedure guidance, picture procedures and improved communication. As the programme moves forward with BBV Safe at Heart modules 3, 4, and 5, the working environment will be set by its leaders, peer-to-peer feedback in real-time will be encouraged and real understanding of the behaviour BBV need to change will happen by communicating with the people demonstrating that behaviour. Individuals willing to challenge unsafe acts are the mentors of a healthy and enduring safety culture.

This behaviour programme is for all people on the project, who work alongside one another which poses significant challenges regarding worker safety, silo mentality, competitiveness, and scepticism leading to unsafe behaviour. However, by taking responsibility, ownership, and accountability for colleagues, giving clear active communication, and a coaching style of leadership that the BBV behaviour programme offers it’s a clear winner.

This paper shares BBV best practice and learning from implementing its behavioural safety programme on the HS2 project. It will be of interest to other projects considering developing their own behavioural safety programmes.

Acknowledgements

Support of the BBV Directors, Heads of Safety, HS2 Directors, Head of Learning & Development and the wider parent companies of Balfour Beatty and Vinci.

A special thank you to the Director of SSHEWE Martin Brock and to Neil Johnson the new SHE Director for continuing to champion and supporting the BBV Safe at Heart behavioural programme.

All those who made the Safe at Heart behavioural programme possible, the peer trainers, the subcontract working party, especially Tim Jackson

Lee Griffiths (Health & Safety Engagement Manager) for his personal support in this paper, presenting training all the peer trainers, and leading the supply chain workshops.

Natalie Griffiths (Enabling Specialist) who has worked tirelessly in promoting the BBV behavioural programme and supporting contractors.

Robert Gillespie for the support on the health aspects of this ensuring health is as important as safety.

All the BBV workforce and the supply chain for making the BBV Safe at Heart behaviour programme a success this far and making BBV a safe, collaborative, and proud project to work on.

References

- HSE (2022) Construction statistics in Great Britain, 2022. Accessed 21 October 2023.

- Donald and Young (1996) Managing safety: an attitudinal-based approach to improving safety in organisations. Leadership & Organisational Development Journal 17 (4), 13-20

- Mearns, K & Yule, S (2009) The role of national culture in determining safety performance: Challenges for the global oil and gas industry, Safety Science, Vol 47:6, pp 777-785

- Langford, D., Rowlinson, S., & Sawacha, E. (2000) Safety behaviour and safety management: Its influence on the attitudes of workers in the UK construction industry. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, Vol. 7: 2, pp.133 – 140.

- Heinrich, Herbert William. 1931. Industrial accident prevention: A scientific approach. New York. McGraw-Hill.

- Bird jr., F.E. & Germain, G.L. (1966) Damage Control: A New Horizon in Accident Prevention and Cost Improvement

- Carter, G., & Smith, S. D. (2006). Safety Hazard Identification on Construction Projects. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 132(February), 197–205.

- Fleming, M & Lardner R (2002). Strategies to promote safe behaviour as part of a health and safety management system, health and safety executive contracted research report. pp 38.

- Fang, L., Zhong, M., Hou, Y., and Chen, X. (2019). Research on the influence of group safety behaviour of agricultural enterprises on production safety performance. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2019, 137–144.

- Jiang, X. L., Mao, C. J., and He, H. (2020). Summary of research on unsafe behaviours of construction workers. Constr. Saf. 35, 70–74.

- Martínez-Córcoles, M.; Gracia, F.; Tomás, I.; Peiró, J.M. Leadership and employees’ perceived safety behaviours in a nuclear power plant: A structural equation model. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 1118–1129.

- Guo, B.H.W.; Yiu, T.W. Developing Leading Indicators to Monitor the Safety Conditions of Construction Projects. J. Manag. Eng. 2016, 32, 04015016.

- Tong, R.; Yang, X.; Parker, T.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Q. Exploration of relationships between safety performance and unsafe behaviour in the Chinese oil industry. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2020, 66, 104167.

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A. Perceptions of safety at work: A framework for linking safety climate to safety performance, knowledge, and motivation. J. Occupational. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 347–358.

- Lingard, H, Rowlinson, S (2005) Occupational health and safety in construction project management, Spon Press.