Collaborative Strategies for Resource Optimisation in HS2 – Supply Chain Collaboration Hub and SCM+

In 2019 HS2 Ltd, as the client organisation and delivery body for High Speed Two (HS2), faced the challenge of launching major construction activities across its four main civil engineering works contractors. It was imperative to ensure value-for-money in subcontract procurement while avoiding market overheating. To address this, a formal mechanism was created to encourage collaboration between contractors, helping them work together to optimise resource use and mitigate risks for the benefit of the whole project.

The initiative aimed to prevent excessive contractor demand from straining supply chains, while also considering external factors like inflation, supply constraints and carbon costs. This collaborative approach led to several benefits such as early identification of supply risks, including the availability of critical materials, smoothing demand to improve overall outcomes, and leveraging the project’s scale to achieve coordinated procurement, securing the best value-for-money.

Key lessons learned included the critical importance of establishing such collaboration early, particularly when contractors would otherwise compete for similar resources. Early client leadership was also vital in setting clear objectives for the collaborative forum and maintaining focus on programme delivery. Additionally, improving supply chain visibility and enabling data sharing across contractors was essential for informed decision-making, particularly in managing supply chain risks.

This learning legacy will be of interest to project managers, procurement, supply chain and commercial professionals working on large-scale infrastructure projects.

Background and industry context

HS2 is the largest infrastructure project the UK has undertaken for decades. Between London and the West Midlands, the construction of the railway comprises 64 miles of tunnel, 500 bridges, 70 cuttings and 50 viaducts, alongside four new stations and one depot. Although HS2 is an enormous programme of works requiring the mobilisation of huge amounts of resources, HS2 Ltd as a client body generally procured very few, very high value construction related contracts. These included:

- Three joint venture enabling works contractors (delivering demolition, ecology, archaeology and utilities works).

- Four multi-billion joint venture civil engineering contractors (delivering the construction of the route including all earthworks, viaducts, bridges and tunnels).

- Four separate contractors to build each station.

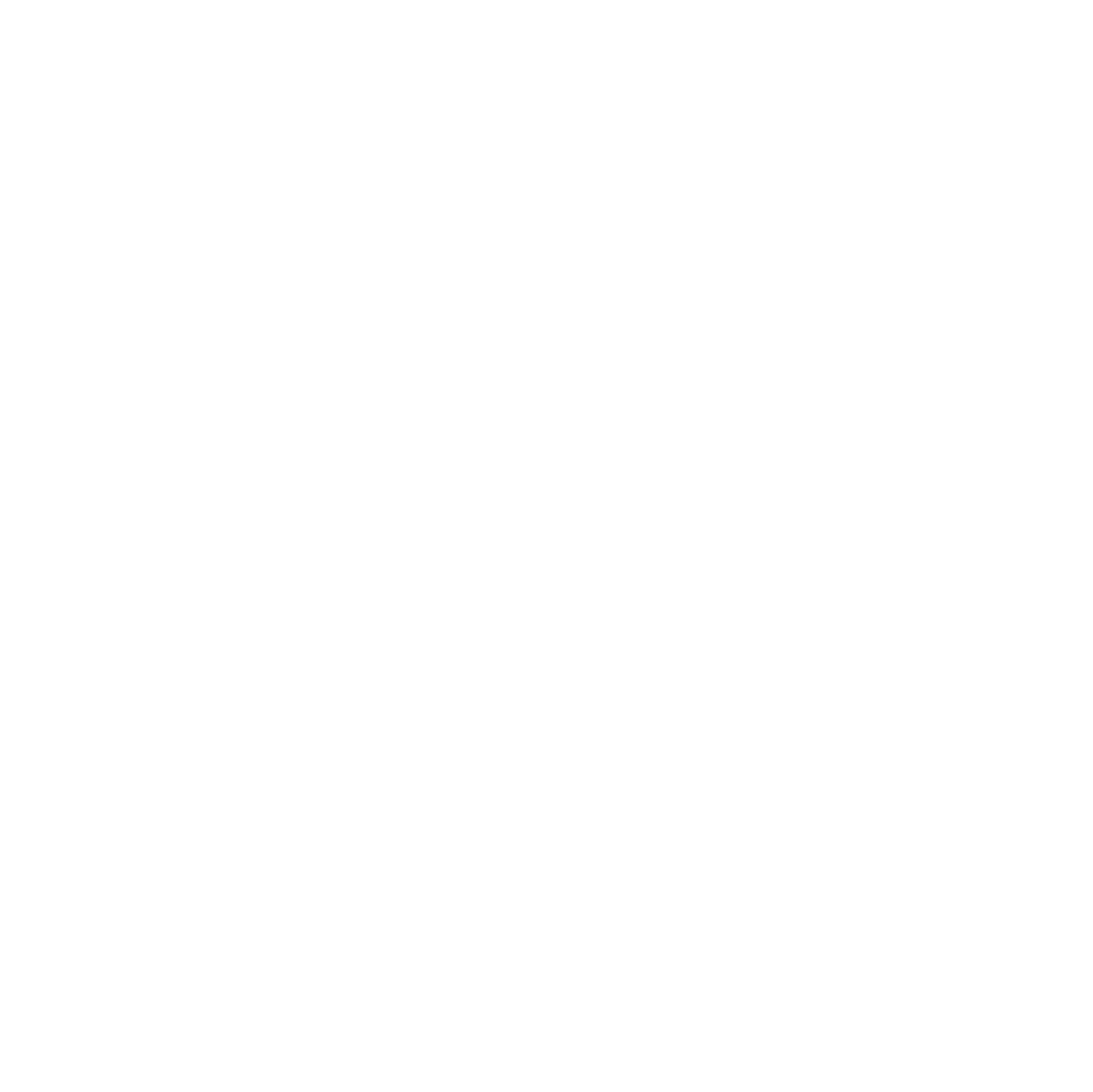

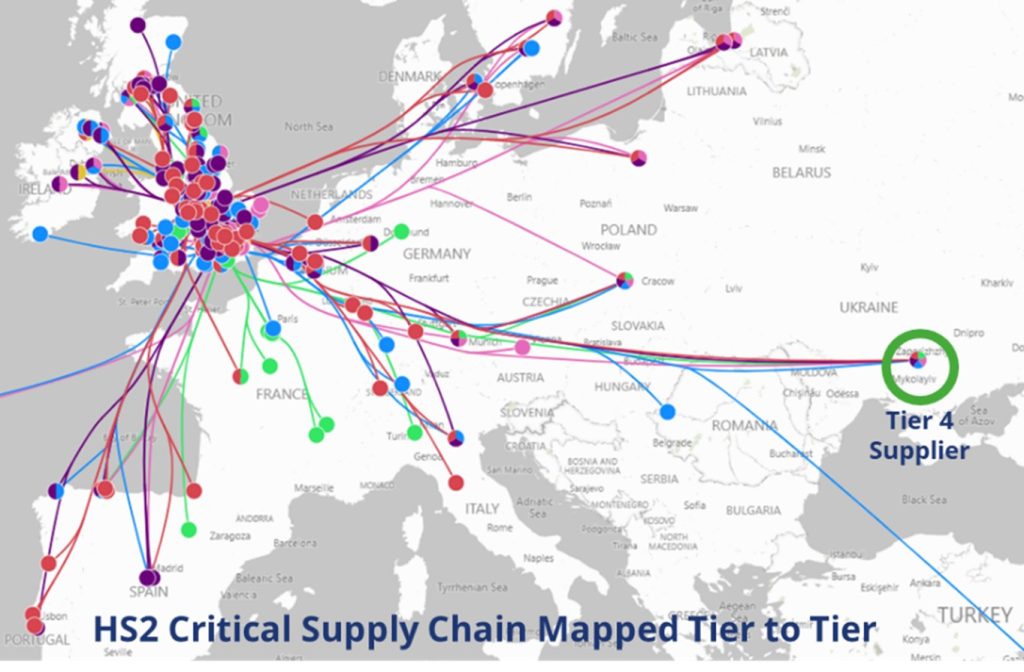

Construction in the UK is typically an industry with opaque, very deep and complex supply chains. Developing collaborative relationships and understanding visibility is challenging as the industry is fragmented and much of the work on a project like HS2 is broken into stand-alone projects made up of unique combinations of contractors and suppliers. “Tier 1” contractors (directly contracted to the client) typically oversee the procurement, mobilisation, management and delivery of the works via this extended supply chain (indirectly contracted to the client), through multiple tiers (see Figure 1).

This is often without full visibility of the suppliers who are delivering resources, especially as they become further removed from the client and tier 1 contractor (e.g. tier 3 and below). Tier 1 contractors procure their subcontractors (tier 2s) who in turn procure their suppliers at tier 3 and so on down through the layers of the supply chain.

As the supply chain extends, the visibility of the source of certain resource supply is often lost and with this comes the risk of a loss of management information and control. Suppliers at all tiers require a mixture of plant, labour and materials to operate, which draws upon further third-party resources. In major UK construction, it is typically the suppliers at tier 2 and below within the supply chain that produce the bulk of labour, plant, products and materials required to deliver the works on site. The tier 1 contractors typically coordinate this resource from a design, engineering, management, logistics and integration perspective to ensure delivery and the sequencing of activities is conducted efficiently, safely and meets the client’s requirements.

The extremely complex nature of such large-scale infrastructure projects, where multiple tier 1s are mobilised with their multiple supply chains, is further compounded when these multiple tier 1s are delivering similar activities using comparable resources in a parallel timeframe, as is the case on HS2. Given the commercial confidentialities and geographic interfaces between each contractor and their contractual boundaries, having visibility and understanding of the whole supply chain is key to managing construction efficiently and responding to risks or opportunities in a coordinated and collaborative way.

The approach developed by HS2 Ltd built upon the learnings from the London 2012 Olympic Games and Crossrail (now the Elizabeth Line), two major construction programmes which pioneered the implementation of deeper supply chain visibility for the purposes of supplier risk monitoring. HS2 Ltd adopted these principles and took the approach to the next level by implementing collaborative contract clauses and working arrangements with its contractors to proactively manage these risks and respond to market changes.

Recognising the need for collaboration across such mega-contracts and given HS2’s scale and geographic reach, in 2016 HS2 Ltd included a ‘Collaboration Agreement’ within its NEC3 Engineering and Construction Contracts (New Engineering Contracts, Version 3) to facilitate and require the tier 1 Joint Ventures (JV) to work together with “cooperation, coordination and collaboration to ensure ‘best for project’ outcomes”. The approach to collaboration set out the general principles, expected behaviours and tone for the relationships. It also ensured access to information across parties, upon the reasonable request of the employer, and established an integrated collaborative team environment. Adequate adoption during the long, often challenging phase of delivery requires client commitment, alignment, active monitoring and benchmarking to ensure client-contractor relationships remain honest, open and with healthy commercial and performance tension.

In turn, the JVs were required to share best practice, coordinate work schedules, provide progress reports and health and safety updates at a Collaboration Board, at which senior leaders from client and contractors were represented and ‘best for project’ decision making undertaken (each party had one vote). The Board was designed to be a forum where parties could raise issues relating to the interfaces between contracts, review and modify the collaboration objectives and enable open discussions relating to project delivery. It was to meet within a month of the agreement (and at least every two months thereafter), with each party to appoint a representative. It was nonetheless important to ensure alignment with commercial and delivery teams to implement ‘best for project’ recommendations presented at Collaboration Board, which itself was not a formal decision-making authority. An appropriate mechanism to review, consider and decide upon cross-cutting risks and opportunities at a holistic level with budget accountability is needed.

Through a contractual requirement for submission of monthly contractor procurement schedules and subcontract data, the HS2 Supply Chain Management (SCM) team had developed a strategic view of the JVs’ procurement of critical subcontracts and supply chains, since the main civil engineering contracts had been awarded in 2017. An opportunity to gain strategic value from across the civil engineering contractors was identified and the HS2 SCM team established a Supply Chain Collaboration Hub (“Hub”) in 2019.

Approach

To establish the Hub, the HS2 SCM team identified suitable counterparts within each civils contractor to invite them to join. This was typically the Heads of Procurement or Supply Chain Management or nominated representative as they deemed appropriate. At the first meeting the rough ground rules were determined, including an agreement to meet on a weekly basis, alongside a nominated ‘client lead’ from HS2 Ltd.

The Hub drew up an agreed Terms of Reference which was developed and refined over time, retaining the core principles. A governance model for the group was established to provide accountability at a senior level in both the JVs and HS2 Ltd, by reporting to the Collaboration Board as set out in the Collaboration Agreement within the contracts.

Initially, the Hub identified some barriers to collaboration, not least the Competition Act, which prevents the abuse of a dominant position in the market and any market manipulation or distortion. The scale of demand from HS2 was such that these issues needed to be navigated and legal advice was taken in relation to the Competition Act. This determined that a coordinated and collaborative approach specific to HS2 subcontract procurement was allowable. HS2 Ltd, as client coordinator of the Hub, would work to ensure competition was not restricted, that transparency was maintained and confidential procurement or contractual information was kept secure and not shared between JVs. This ensured that individual parties’ commercial sensitivities were protected and the market was not distorted.

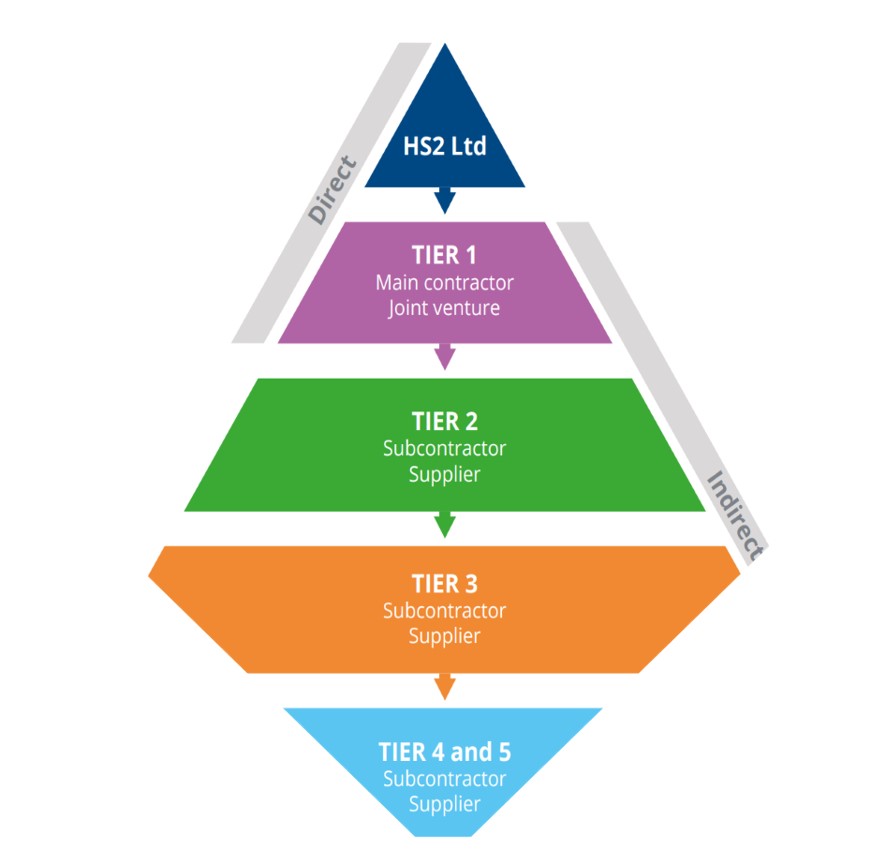

All work undertaken within the Hub is framed under the 5-pillar model described in Figure 2, below. Each pillar has a volunteer ‘lead’ representing one of the contractors, who then work collaboratively across the group to progress their pillar. A weekly joint meeting focuses on one-two pillars each week (rotated each month), with a separate monthly leadership meeting including senior HS2 stakeholders and the Department for Transport’s Project Representative. This structure provides a focus for the Hub’s activities, typically centred on cost efficiency, market intelligence and sustainability. It is worth noting that since the inception of the Hub, initially with the four civil engineering contractors, HS2 stations contractors voluntarily joined the Hub in around 2020.

The approach to collaboration was designed to focus on achieving greater value and avoiding market over-heating, while remaining inside the rules of the Competition Act and navigating global demand and supply pressures for the benefit of the programme. The external impacts that the macro-economic environment has on supply, while beyond the control of the HS2 supply chain, can impact its ability to deliver. As a result, the analysis completed constantly had a ‘weather eye’ on these emerging and changing factors.

Taking a strategic and integrated approach to issues relating to procurement, supply chains, carbon, materials, inflation, resourcing and much more, the Hub has focussed on a wide range of activities including:

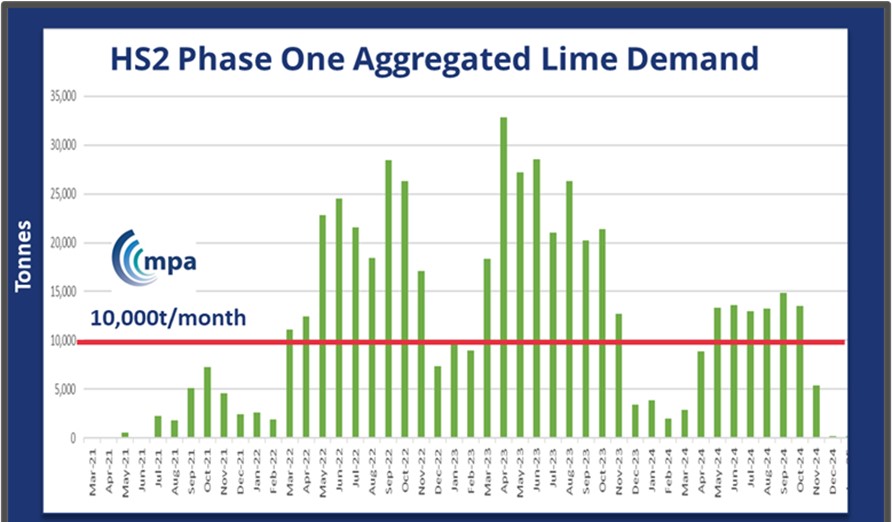

- Identifying opportunities and threats in relation to common procurement and contract categories across HS2’s main contractors (for example steel, concrete, cement, lime, timber, mechanical & electrical, labour etc), with the objective of making “best for project” procurement and efficiency decisions. For example, once it was identified that aggregated HS2 demand was at risk of exceeding UK lime supply (a key ingredient in soil stabilisation, water treatment and concrete production), the Hub worked closely with the UK lime industry, through trade bodies and directly with producers, to communicate demand and develop the industry’s capacity.

- Ensuring capacity constraints were appropriately identified and mitigated within and across HS2 supply chains. For example, the supply of steel reinforcement bar (rebar) used for concrete structures was severely constrained in 2021-22 as industry emerged from the COVID-19 pandemic. This necessitated close working with UK Steel and the British Association for Reinforcement, to ensure proactive communication and coordination of demand at an industry level, in order to help secure supply. While delays were incurred, the impacts to the project would likely have been greater without the strategic working of the Hub.

- Share macro and micro market intelligence. For example, HS2 SCM developed a live commodity dashboard showing price movements for 38 commodities and 32 macro-economic indicators, to provide contractors with the latest intelligence to inform buying decisions (see Figure 4).

- Supply chain development programme. It was essential to upskill suppliers to a common standard across the project in key areas including health, safety and wellbeing, sustainability, carbon reduction, community engagement, skills, education and employment, etc. The Hub partnered with the Supply Chain Sustainability School to develop and deliver this through a bespoke, interactive learning platform and series of events. Over 300 businesses accessed the platform within the first year, which provided 6,000 free training hours and 2,000 e-learning resources.

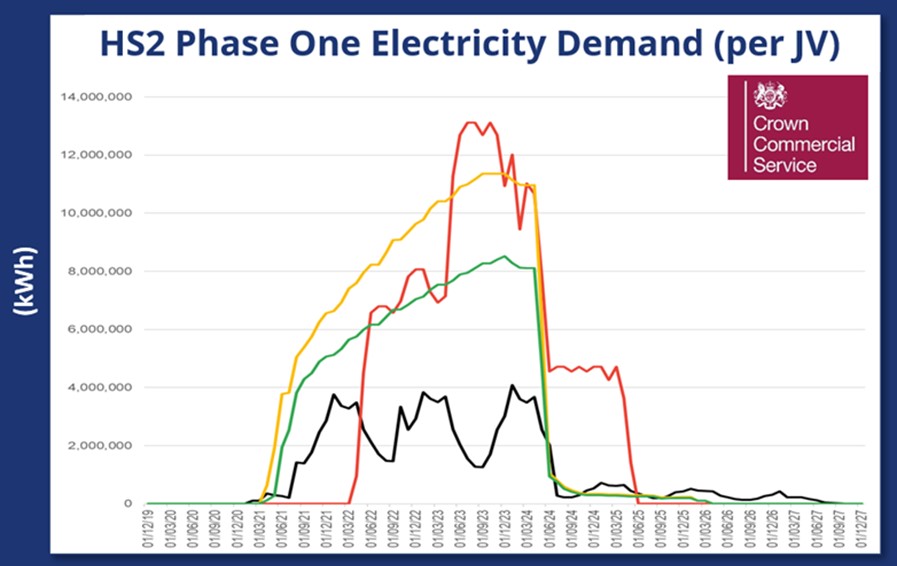

- Pursue opportunities for strategic procurement either through collaborative or coordinated activities to achieve greater value for HS2. For example, HS2 and the Hub worked with Crown Commercial Services to secure centralised renewable electricity supply for all contractors, a market saving worth in excess of £10m.

- Work collaboratively in the interests of the project to pursue other areas of mutual benefit and efficiency (e.g. logistics, interfaces, innovation, programme schedule etc.). An example of this came through adjusting the schedule across two separate contractors for tunnel slip-forming walkways, a highly specialist construction activity with a limited supply market. By smoothing demand, this removed the need for a subcontractor to purchase additional plant which would have incurred additional cost to the project.

Market Risk Analysis

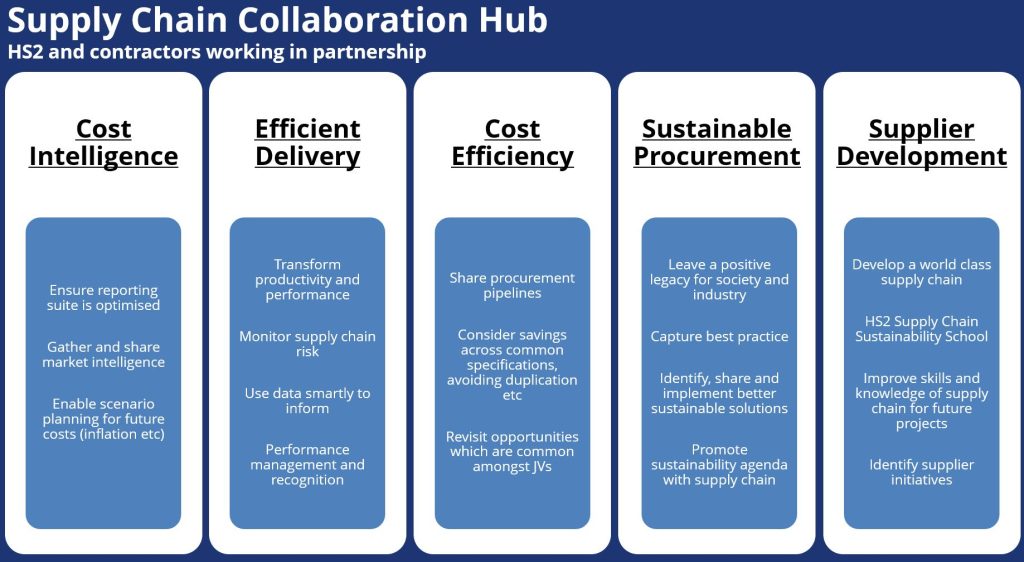

A key tool developed by the Hub and managed by HS2 SCM was the Market Risk Analysis Tracker (MRAT) shown in Figure 3 below. This dashboard was made up of key commodities assessed to be of importance to the ongoing delivery of HS2. With commercially sensitive data redacted, this tracker was used as a single source of truth for tracking historic price fluctuations and trends across ten strategically important commodities.

Meeting weekly, the Hub used the MRAT to assist the JVs’ view of market movements and inform procurement decision making, e.g. on whether to hedge, apply ‘cap and collar’ approaches, spot-buy short-term demand or defer large orders, to avoid over-heating or over-committing during a heightened market. It also aided understanding of the key drivers for positive and negative price changes and market influences. Subjective predictions of future price movements, based on past data and the Hub’s market knowledge, was added to help users make more strategic decisions on future buying options.

For the ten priority commodities, the MRAT displayed the latest Building Cost Information Service (BCIS) monthly commodity data (columns 1-3), against a December 2019 baseline. It then analysed the potential cost impact of that inflation on the basis of total HS2 forecast demand for that commodity (columns 4-5). It also subjectively assessed the degree of overall risk, future supply vulnerability and expected forward cost pressures (columns 8-10), using a simple Red/Amber/Green/Black status. The sparkline showed the trend in price movements since December 2019, with the impact of the Ukraine conflict in 2022 clearly displayed. At the height of the crisis, prices for critical commodities including steel and concrete jumped by 30-40% in a short period of time. This coincided with when HS2 needed to buy significant volumes of material, significantly impacting the cost base for the project. While the price of some commodities moderated in the years following, others – most notably concrete products – continued to rise albeit at a slower rate. A more detailed Commodity Dashboard, including data on 38 different commodities, was developed using Power BI. This drew upon a range of data from third-party sources (including Building Cost Information Service[1], Office for National Statistics[2], World Bank[3], etc) and was updated on an almost ‘real time’ basis once the source data refreshed at different intervals. Figure 4 shows the month-on-month percentage movements of different commodities, as a summary example. As the tracker resided in a Microsoft Teams channel, it enabled a self-service function for both HS2 and contractor teams to access.

As a result of analysis tools like the Commodity Dashboard and MRAT, HS2 contractors were able to share intelligence and make more informed purchasing decisions. However, the nature and structure of markets like steel and concrete meant that offering long-term demand in exchange for price security was rarely feasible. This was due in part to the business models of producers but also because of the extreme market volatility at the time. Energy-intensive industries such as steel were highly exposed to volatile input costs such as energy, as well as changes to regulatory regimes, for example the price of carbon credits, which were often higher in the UK relative to overseas competitors. This is an example of how the assumed economies of scale benefits of major infrastructure projects can be limited beyond a certain point, or indeed be counterproductive, due to the sheer scale and nature of risk management down the supply chain in response to an uncertain world.

Supply Chain Management +

As an additional workstream to support the Hub, Gardiner & Theobald LLP were commissioned in 2021 to mobilise a “Supply Chain Management Plus” (SCM+) team to undertake targeted deep dives of critical categories, products and supply chains that were common across all JVs. These deep dives mapped the end-to-end HS2 supply chain for piling, rebar, timber, precast concrete, structural steel and earthworks, drilling down to tier 4-5 in the supply chain. This reached the source of raw materials which, while predominantly UK-based, often stretched across Europe.

One example of the benefits this workstream delivered was the piling deep dive. Piling is a critical activity which bores foundations deep into the ground, up to 30m on HS2. Through direct conversations with different suppliers at each tier, followed by data capture, the supply chain was mapped down to tier 4 (see Figure 5) and identified that all four of the civils JVs were sourcing rebar from the same Ukrainian manufacturing facility in Mariupol. Given the Russian invasion of Ukraine had just occurred, this work became extremely important and timely in helping HS2 Ltd and its JVs identify six contracts worth more than £40m which impacted over £0.5bn of contracts at tier 2. This intelligence of the specific exposure to unfolding global events enabled the JVs to make alternative sourcing arrangements. The ability to make this decision expediently removed the risk to supply and the potential negative impact on cost, schedule and delivery.

This enhanced supply chain visibility, at a category level, provided a critical understanding of the complex flow of raw materials through the tiers of the supply chain. In meeting with individual critical suppliers on a 1:1 basis, the team were able to collate quantitative and qualitative feedback on live operational and logistics issues, for example issues with UK port and rail freight capacity, which SCM could feed back to relevant tier 1 contractors to improve performance and unblock issues. It is worth noting that not all suppliers engaged were even aware they featured in the HS2 supply chain, such is the upstream and downstream opacity of construction supply chains where individual orders would be made by distributors, fabricators etc., in response to the demand placed by their portfolio of clients.

A key learning legacy of this work is that while this visibility was valuable, the ability of HS2 and contractor teams to quickly implement changes, in response to the risks and issues identified, was hampered by the fact these issues were occurring deeper into the supply chain, beyond direct contractual relationships. There was also a reluctance from a client level to intervene directly in the operations of the supply chain, which would have bypassed contractual relationships and potentially imported additional risks which HS2 Ltd was not set up to manage.

In addition, this work was relatively resource intensive, requiring personal approaches to individuals within individual suppliers, tier on tier, to obtain the data and insight through specific meetings, sometimes face-to-face. A systematic challenge of the UK construction sector is the highly fragmented and opaque nature of supply chains. Therefore, ensuring clients have maximum visibility of the end-to-end supply chain is a critical enabler to managing risk. Developing a systematic approach to acquiring this data, perhaps via a centralised digital platform, which mandates suppliers at all tiers to provide their data in return for improving their own visibility of the whole ecosystem, would be a great step forward for future infrastructure programmes. However, ensuring supplier compliance and data accuracy during complex and fluid construction programmes may continue to be a challenge.

Outcomes

Across the programme there were countless examples of the benefits that derived from adopting a collaborative approach. As referenced earlier in the paper, the HS2 SCM team identified that the HS2 demand for lime exceeded available UK capacity (see Figure 6, with the red line being estimated UK supply capacity). When non-UK production was investigated it was realised that on top of additional logistics cost the import tariff would add more than £60/tonne to the product cost. To mitigate overheating domestic supply, UK supply was secured via early engagement with UK lime producers, facilitated by the Minerals Products Association. This resulted in one domestic supplier increasing their output by opening additional kilns and storage silos. The collaboration created a 100% increase in future UK lime production and over 100 new jobs as well as identifying an additional source of lime from the by-product of steel production. These additional value elements were on top of a cost saving of over £100/tonne and illustrate the value of strategic industry engagement at a programme-level.

A further example of strategic thinking relates to electricity supply. The Hub identified an existing public sector framework established by Crown Commercial Services that provided renewable supply. HS2’s contractors had extremely high peak demand for electricity (see Figure 7), not least due to the 24-hour running of up to ten Tunnel Boring Machines (TBMs). It was identified by the Hub that there was a lack of competition in the energy market which was driving up energy costs, compounded further due to global events such as the Ukraine crisis. To mitigate these risks, it was established that by providing the JVs with ‘Agent’ status, they could purchase electricity via this procurement route. Therefore, working with HS2’s legal team, ‘Agent’ status letters were provided to enable access to the framework for each JV. This provided cost savings against the market rates of between 9% and 12% and ensured that 100% of the energy was from either recycled or renewable sources, presenting a significant carbon saving.

Collaboration Awards

The approach delivered by HS2 in collaboration with its tier 1 contractors was recognised by the Institute for Collaborative Working at its 2022 annual awards ceremony. The team won the Industry Collaboration Award, for its work to gain visibility of the sub-tier supply chain to drive open dialogue, facilitate risk mitigations, share information, pursue innovation opportunities and even resource share across contractors. The collaboration workstream, while driven by HS2 Ltd and its contractors, also empowered all tiers of the supply chain to work towards shared HS2 goals as opposed to focusing on individual benefits. Opportunities for novel or beneficial procurement techniques were identified and shared across the Hub, resulting in cost avoidance, reduced costs, and alignment to sustainability goals, such as the creation of apprenticeships, low-carbon solutions, access to training and community benefits through a “balanced scorecard” approach to procurement.

In 2023, the team was commended at the British Construction Industry Awards for ‘Partnership of the Year’. Judges commented that “HS2 is an incredibly impressive project at a different scale to most construction projects. The team gave a compelling presentation, showing an integrated approach at national level to managing the supply chain. The partnership ethos was evident in their novel approach to sharing information across the supply chain to drive ‘right for programme’ as well as ‘right for partner’ decisions. This is evidently a partnership that demonstrates mutual respect across the supply chain.”

Learnings and Recommendations

The HS2 Supply Chain Collaboration Hub has been an evolving model that has grown to achieve success. There have been some challenges to realising this success but at its heart the spirit of collaboration meant that ultimately these challenges were navigated. The challenges faced, while ultimately not insurmountable did make progress slow to begin with. As obstacles were overcome, trust and relationships were built across the stakeholder groups.

Contractors generally appreciated the fact that collaboration was driven by HS2 Ltd from the outset, with clear, consistent messaging and mechanisms (e.g. forums) established, supported by contract clauses. The Collaboration Hub has been greatly valued by the JVs – the shared view is that HS2 Ltd has invested in and facilitated an industry-leading process, underpinned by proper governance. Consistency of Hub membership, over many years, has developed strong personal relationships and trust, with a willingness to openly share (non-commercially sensitive) information, develop opportunities and proactively manage holistic risks during highly challenging market conditions.

However, feedback also suggested that the agenda for collaboration could have been more operational and integrated from the outset, with HS2 Ltd taking more of a lead role to align the Hub’s activities with project objectives, mandate the use of common data and reporting platforms and pursue opportunities to standardise processes, design approaches and commodity procurement (for instance by nominating one JV to procure materials on behalf of the others through ‘buying clubs’). Perhaps greater programme-level incentives would have driven the JVs to engage in a higher number of collaborative procurements. Or HS2 Ltd could itself have taken ownership for the procurement of key commodities and free issued to the supply chain. The fact that each JV was operating to a different schedule, strategy and at different levels of maturity made collaborative procurement challenging.

Standardisation and alignment opportunities at scale were missed as separate subcontract designers were engaged to carry out detailed design for different sections of the route, creating resource inefficiencies. Comparing schedules when it came to commodities or procurement activities was not done to the extent that it could have been, which could have prevented unnecessary competition in the market – this needed continual programme evolution and recalibration, as well as a more prominent leadership role for the client.

The key learnings and recommendations for any organisation looking to bring collaboration across multiple complex contracts and their supply chains, to achieve value and best for project decisions, can be summarised as follows:

- Establish the Terms of Reference collaboratively and ensure that the governance model for collaborative decisions is in place early and clearly understood. Ensure senior (Director/Executive-level) sponsorship is in place throughout and refresh accordingly, to drive outcomes.

- Ensure the right people and professional experts are engaged and have suitable skills for the point of the commercial cycle being discussed (e.g. procurement people when discussing subcontractor engagement, selection and mobilisation; commercial, project management and supply chain management people during contract and wider supply chain delivery). A balance must be struck between needing to ensure continuity of relationships and obtaining appropriate representation at different phases and across different disciplines of work.

- Identify and prioritise the categories of mutual criticality for review, investigation, monitoring and targeting for efficiency gains. The nature of a major construction programme means there will be no shortage of opportunities, but the nature of markets and different contractor strategies and schedules may introduce constraints. Efforts must be directed at the most viable opportunities.

- Establish the right client-level capability for oversight to ensure confidentialities are preserved, to act as an ‘honest broker’, shape the framework and mechanics of the group, areas of focus and to drive outcomes. This should be driven by a programme-wide Supply Chain Management function who should appoint people with the right collaborative behaviours and strategic, entrepreneurial mindset. Early identification of client priorities for collaboration, connected to project outcomes, milestones or commercial models, may assist in creating incentives to drive collective action.

- Ensure that all parties have the right datasets (e.g. procurement pipeline data, data on commodity demand volumes linked to schedules, specification or technical data, live subcontract data, supplier contact details etc), to enable analysis across the programme. This can be included in the Works Information (for NEC contracts) to ensure up-to-date subcontract procurement and contracting data is always available to the client.

- Do not make data gathering onerous and make data requirements aligned to the data which any project or contractor should hold as part of their own oversight and management. Integrate this from the outset and mandate centralised, consistent digital platforms for reporting (contract data, carbon, etc) which is made available to the whole supply chain. While HS2 Ltd had systematic visibility of tier 2 subcontract data from the JVs (shared on a monthly basis), there was no mechanism in place for gathering subcontract data beyond this.

- For the SCM+ supply chain deep dives, develop a systematic approach to client-side data gathering and analysis to preserve confidential data while navigating the requirements of regulation and public policy (e.g. Procurement Policy Notices which require data on steel supply chains for public projects). Embed into contractual requirements which are flowed down into the supply chain; ensure this is regularly monitored and engage directly with suppliers as required so they understand the reasons for the data capture and can receive some benefit in exchange (e.g. intelligence on how they are positioned within the whole supply chain, which they may not be aware of).

- Establish a regular meeting and reporting regime to ensure the approach to collaboration is regularly reviewed and progress is both maintained and monitored. The HS2 approach of weekly Collaboration Hub meetings split by theme/pillar, with a monthly leadership review meeting, was considered the right frequency for the programme, however reporting and sponsorship linked to formal HS2 processes, internal functional leads and decision panels could have been strengthened.

- Ensure the right client-side structures and governance are in place to facilitate timely and efficient decision-making in response to live risks or opportunities. This may require clients to take on a degree of risk, so understanding the client’s risk appetite and the degree to which it wishes to intervene in its supply chain is a key enabler. Ensure these structures are regularly refreshed and continue to operate as intended with the right level of sponsorship – be alive to any scope ‘drift’ and hold decision makers to account.

- Create an environment for shared learning and open and honest conversation, based on trusted relationships. Open dialogue can be a valuable source of intelligence and knowledge-share and help to differentiate between fact and hear-say. Peer pressure and reputational leverage, as well as personal and professional pride, can be a powerful motivator for all parties to perform to their potential.

Conclusion

This learning legacy sets out the key findings from the HS2 Supply Chain Collaboration Hub, a partnership working group across the procurement and supply chain leads of HS2’s main contractors, from 2019-2024. Given the fluid and dynamic nature of construction markets, the complexity of major programmes and their vulnerability to external trends and influences, procurement and supply chain professionals should prioritise the establishment of collaborative working structures with key supply chain partners, at an early stage. This can help to realise efficiency opportunities, build visibility of supply chains, avoid risk and respond to unforeseen events, helping to safeguard the sustainability of supply chains and ensure value for money.

Acknowledgements

Gardiner & Theobald LLP

References

[1] Building Cost Information Service. BCIS | Building Cost Information Service Construction Data [Internet]. Coventry: BCIS; 2024 [cited 2024 Nov 1]. Available from: https://bcis.co.uk/

[2] Office for National Statistics. Inflation and price indices [Internet]. Newport: Office for National Statistics; 2024 [cited 2024 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices

[3] World Bank. Commodity markets outlook [Internet]. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2024 [cited 2024 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/research