Designing and assuring the UK’s largest ever human remains reburial programme

The reburial programme on HS2 Phase One is unprecedented: never has an engineering project been faced with the challenge of such numbers of buried human remains to remove, look after and rebury – over 30,000 people. The legal framework is also new – while the requirements of the High Speed Rail Act mirror those of other projects, an additional legal Undertaking with the Archbishops’ Council of the Church of England, along with HS2’s values of integrity and respect mean that for the first time religious and public scrutiny have truly provided the parameters for programme design for a task of this nature. This has helped HS2 to deliver a result that can stand up to ethical and public challenge as a unique case study for future projects – for later phases of HS2, and other largescale infrastructure programmes. This paper describes how the technical, legal, commercial and ethical requirements of the project have been translated into the process of selecting and negotiating with appropriate sites for reburial. It highlights key challenges presented by the project’s circumstances and the impact of contemporary issues and commercial considerations on the programme. The results of the programme for this stage of the work are presented in conclusion.

Project Context

The burial grounds on HS2 Phase One

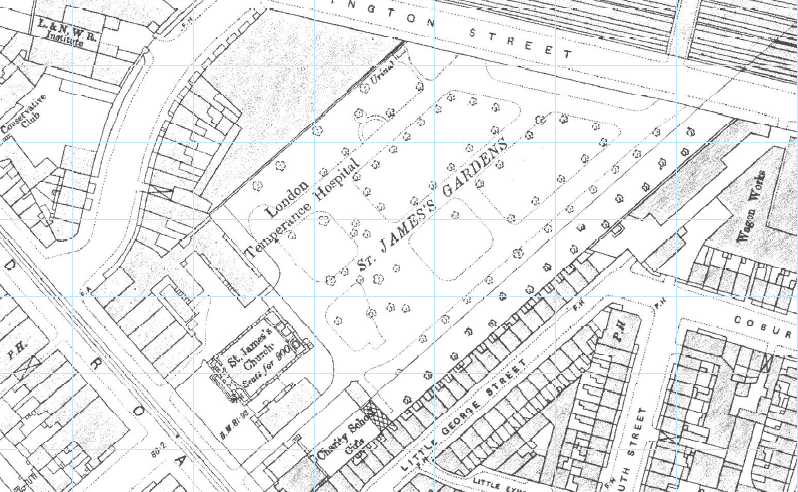

High Speed Two (HS2) work on burial grounds began before 2012 with desk-based investigations for the HS2 Phase One Environmental Statement (ES) [1]. Early studies were commissioned from consultants who in the archives, map rooms and record offices along the line of route between London and Birmingham identified the surprising existence and possible scale of burial grounds that could be affected. These lost places were often unrecognisable in their 20th century guises as city parks, in scrub land and beneath rural fields. Investigation to determine the more precise extent, survival and significance of these burial grounds continued in increasing detail leading up to the start of the Enabling Works Contracts between London and Birmingham in 2017. Burial Grounds will continue to be discovered as Phase One progresses and are also a consideration for Phase Two, where known and as-yet undiscovered burial grounds lie along the route.

HS2 has now part-exhumed three Church of England (CofE) burial grounds on Phase One, as well as over 20 individual burial sites containing human remains dating from the Bronze Age onwards – all of these people buried over 100 years ago (see Table 1). The location for reburial of the majority of these remains has been decided, and several thousand people have already been reburied.

| Burial Ground | Type | Date | Numbers removed before August 2020 (future total estimated in brackets) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

St James’s Gardens, Euston, London (figure 1) |

C of E, overflow cemetery for St James’s Church Piccadilly |

18th -19th century |

15,400 (c.20,000) |

|

Park Street Gardens, Birmingham |

C of E, overflow cemetery for St Martin’s Church, Birmingham |

19th century |

9,900 (c.10,500) |

|

St Mary’s Churchyard, Stoke Mandeville |

C of E, local parish churchyard |

11th-20th century |

100 (c.3,000) |

|

Freeman Street Baptist burial ground, Birmingham |

Local Baptist Meeting House burial ground |

19th century |

Partial remains, fewer than 10 individuals in total |

|

Non-Christian burial grounds between London and Birmingham |

Cremation cemeteries and burial grounds containing varying numbers of individuals each |

Bronze Age to Medieval |

Over 45 individuals at time of writing, total number not possible to estimate |

The sections of this paper describe:

- the project context, including comparisons of the HS2 situation to other examples;

- the project requirements – legal, ethical, technical and commercial commitments;

- the reburial programme design risks and challenges;

- the design response to those challenges; and

- the outcomes of the work (the results are in Table 2), with emphasis on structures established for future stages.

Understanding and respecting burial traditions

To embark on the reburial programme, important questions first needed to be answered. Who were the people whose remains HS2 is responsible for, and would their families, histories or beliefs have implications for the work? How many had survived over a century of railway and station development at St James’s Gardens near Euston Station, and Park Street Gardens near Curzon Street, Birmingham, and in what condition? What is the significance of a cemetery of over 30 people discovered at Ellesborough, Buckinghamshire or a Roman period lead coffin burial at Wellwick Farm nearby (figure 2)?

The populations of the large urban burial grounds reflect the breadth of 18th and 19th century society – from the richest to the poorest, the famous and infamous, criminals and captains, people from the neighbourhood, from beyond the city, from Europe and the world – at the time of the British Empire. At St Mary’s Stoke Mandeville they were mainly those who lived and/or worked in the parish, many of whose descendants still live nearby. The smaller burial sites contain the remains of individuals who lived and worked in England more than 1500 years ago, who shaped our landscape and were for some of us, our ancestors.

All of these people were buried within their own belief systems and in the traditions of their time – their stories the subject of ongoing analysis and future publication by the historic environment team (through the Historic Environment Research and Delivery Strategy [2]). While more ancient beliefs can be harder to decipher, Christians believe that the finality of Christian burial should be respected[3]. This is what the 20,000 Christian, people buried in St James’s burial Ground, Park Street Burial Ground and St Mary’s Church believed, and what their families believed when they buried them.

Removing human remains from burial grounds, and reburying

The CofE are committed to protecting those buried in consecrated ground, making sure they are not disturbed. But we live in a fast-changing, multi-cultural and multi-faith community in modern Britain, and a challenge for the planning system is to balance the varying needs of today’s society. Public attitudes to the treatment of human remains are generally accepting of the need to exhume historically buried remains (over 100 years old) for development, and for scientific study[3]. For this reason, with the Church’s agreement, UK Government can allow remains buried over a century ago to be exhumed in accordance with strict licensing requirements, under Section 25 of the Burial Act 1857[4].

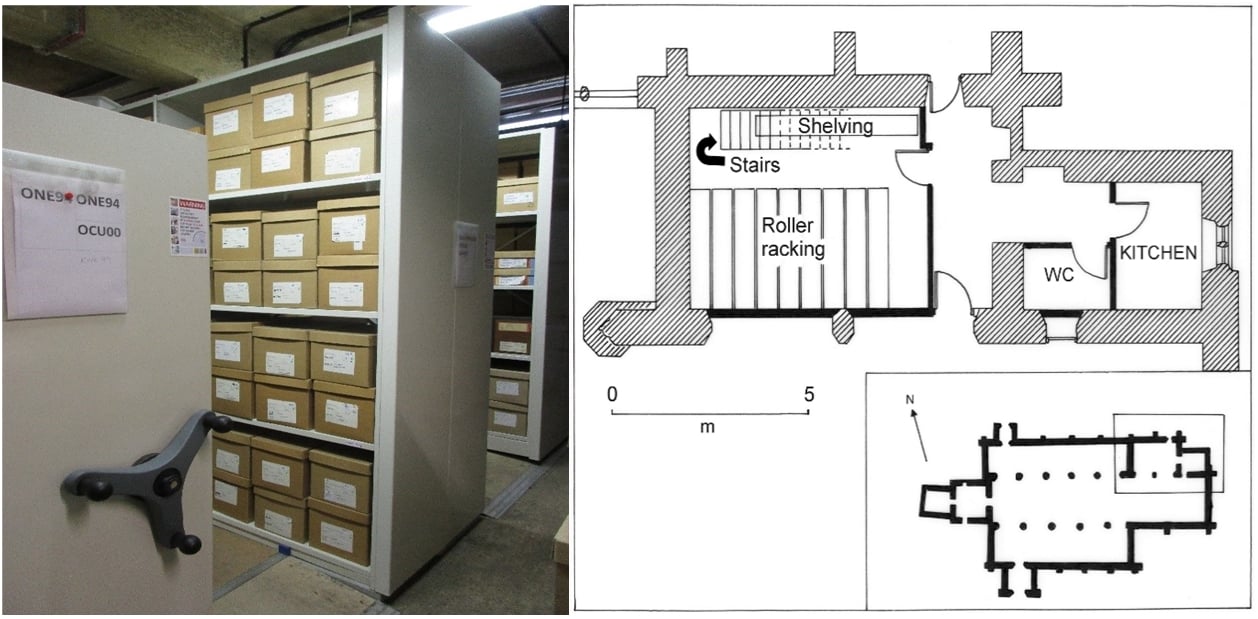

In this context, past major development and infrastructure projects in the UK have also been challenged with the need to remove human remains from burial grounds, both Christian and non-Christian, and to relocate them. Examples include St Mary Spitalfields [5], Bethlem/Bedlam Hospital, for Crossrail[6], St Pancras for HS1[7], St Martin in the Bullring Birmingham[8], the Edinburgh Tram (over 400 medieval/post-medieval graves) and housing developments across the country (including 300 Roman burials found at Yatton in Somerset in 2018). Requirements for how remains are to be treated after being removed from the ground are normally contained within the planning or statutory measures relating to individual projects. In past circumstances, reburial has taken place in a variety of types of location which, due to problems of capacity and urban expansion are frequently unconnected to the original burial ground, sometimes far away, and often quite unlike the original burial situation. Practice has been to rebury in new or privately-owned cemeteries where capacity is affordable, in local cemeteries within the Diocese if possible, or in deposits within the basements of churches if close by. For some remains, including Christian and non-Christian remains, they are not reburied, but kept in museums or archive stores for archaeological research. In a unique example (in 2007), the remains from an excavation of over 2000 people from a church in Humberside, considered to be extremely valuable for future scientific research, were archived within the Church itself, in specially designed research facilities (figure 3), monitored and curated by a committee which includes the Parish Church and local community[9]. Other human remains are kept in museum stores, by local authorities, in university research departments or laboratories.

The entirety of all burial grounds lying along the route of Phase One will be removed prior to Construction, to comply with the requirements of the High Speed Rail (London to West Midlands) Act 2017[10] (‘the Act’). So far nearly 30,000 people will need to be reburied on Phase One, of which 15,000 have come from the CofE burial ground at St James’s Gardens, and more will follow in later stages of work. To put the scale of the work in context, at the time the ES for Phase One was published, St Mary Spital (London) was thought to be the largest excavated cemetery in the world, containing around 11,000 individuals.

Project requirements

The HS2 approach to reburial is underpinned both by legal commitments and by articulated ethical principles. These differ in their nature, strength and extent from any previous infrastructure project as no previous project has been subject to the same legal timeframes, combined with the legal commitments to the Church of England which govern HS2 (see below), nor the articulated commitment to respect and integrity, embodied in HS2’s company values In addition, technical and commercial requirements ensure that the result of the programme also offers value for the public purse, as well as environmental, design, architectural, archaeological and planning excellence, in accordance with HS2’s standards and processes.

Legal commitments

Any location where human remains are identified is, in HS2 terms, a ‘burial ground’. Schedule 20 of the Act (Burial Grounds), is the legal framework within which work with human remains on HS2 is discharged, and includes the requirements:

- to seek confirmation from the Ministry of Justice every time that human remains are identified which are believed to be over 100 years old (replacing S.25 of the Burial Act 1857, disapplied);

- to rebury remains over 100 years old within 12 months; and

- to report to the Home Office on within 12 months of removal of remains over 100 years old.

The Environmental Minimum Requirements (EMRs) which include the Heritage Memorandum[11], stipulate that HS2 carry out archaeological research on historically significant sites – which includes burial grounds over 100 years old. They also require that HS2 engage with Statutory stakeholders Historic England and relevant Local Authorities in the process of carrying out that work.

HS2’s legal Undertaking with the Archbishops’ Council of the Church of England[12] requires HS2:

- to rebury, not to cremate, remains that have been removed, in a consecrated place;

- to consult the CofE on the process of work related to burial grounds;

- to provide a memorial at any reburial site; and

- to replace memorials removed with human remains with the deceased, if possible.

Ethical commitments

HS2 has developed a clear ethical approach to human remains, based on legal requirements, which reflects national guidance and the ethics of professional work in burial grounds articulated by Historic England, the Advisory Panel on the Archaeology of Burials in England (APABE) and others, listed at the end of this paper, valued stakeholders in the project. The HS2 approach, as articulated in HS2’s Technical Procedures (the ‘Burial Grounds Human Remains and Monuments Procedure’) – is that all human remains affected by HS2 are treated with dignity, respect and care. This principle applies regardless of the age of burial, the manner of burial, who the person was, the tradition within which they were buried or whether they were cremated. In terms of corporate responsibility, HS2 has a specific commitment to an ethical approach in the context of its core company values of ‘respect’ and ‘integrity’. These values shape the environment and culture in which HS2 and its supply chain work and reflect the ethics of the company and the way HS2 presents itself to the public, to the media and to its employees. HS2 has a duty to address the concerns of individuals and communities and has open lines of communication with all relevant organisations associated with burial grounds work including the CofE, Dioceses and bodies representing other faiths.

Technical and commercial requirements

HS2 are bound by the technical and operational standards relevant to the reburial of human remains specified by individual burial grounds and professional bodies (such as the Institute of Cemetery and Crematorium Management). Complementary standards and guidance on the treatment of human remains are provided by the organisations mentioned above, concerned with the historic nature of human remains, as well as with their ethical treatment. A reburial on this scale, with associated re-landscaping and memorialisation, is also subject to HS2’s landscape and architectural planning and design standards and processes. Site owners, managers and regulators, as well as national and local organisations who set and impose these standards are all potential stakeholders for the HS2 reburial project.

As a publicly funded project, HS2 is committed to providing value for the taxpayer. The reburial programme has been subject to standard HS2 commercial assurance procedures, underpinned by a financial baseline, and subject to commercial risk assessment as design developed.

Design – risks and challenges

Foreseeing the unforeseeable – a developing baseline

As with anything buried – geological, archaeological or other environmental – setting a qualitative and quantitative baseline is challenging. Knowing the likely number of human remains requiring relocation at the start of the HS2 Project was difficult, despite the application of a full range of predictive techniques. The difference between the predicted number of human remains buried at Euston, for example, at the time of Royal Assent (as reported in the ES) and the actual number found, varied by nearly 25,000. Many more intact coffins than expected were also discovered once removal began. Starting the reburial programme using predicted figures would have required using an overblown baseline in terms of quantities, but also potentially risk selecting an inappropriate reburial situation for the condition and nature of the remains found. The investigation of the sites also threw up other questions affecting the parameters and cost for reburial: would a chosen burial ground be willing to accept burial monuments, potentially in poor condition, and of unknown quantities? Would human remains containing contaminants such as mercury be accepted? In terms of remains from non-Christian burial grounds, the numbers, nature, location and significance of remains were, and still is unforeseeable. Understanding the point at which to start the process of selecting destinations for these remains has been a unique challenge for a project at this scale.

Managing and communicating expectations

Expectations of all infrastructure projects when it comes to burial grounds can be low – images of bulldozers and body bags can spring to the public mind, sometimes fuelled by uninformed media speculation, if information about processes and commitments isn’t shared. This understanding can even filter through into the project itself, where a lack of understanding of requirements can threaten to set the process off on the wrong foot, put off powerful stakeholders, and undermine carefully laid foundations for a legal and supported exhumation and reburial programme. Ensuring that these misconceptions were not held publicly, nor indeed within the project, was an important part of the Phase One team’s communications work. Conversely, raising expectations or providing false certainty where a complex design process is still at work has also been a consideration – early concepts for reburial at one ground have been hard to pull back from, as the requirements of the programme have developed.

Balancing requirements

The Act requirement to rebury human remains within 12 months of removal reflects requirements seen on other projects. HS2 also has unique additional requirements, with commitments to key stakeholders such as the CofE, and to specific heritage outcomes, as well as being of unprecedented scale. Built into the Act, in recognition that issues might arise, were allowances to seek Direction from the Secretary of State for alterations to the timeframe, as well as to the parameters for reburial itself, so that these requirements could be balanced.

The Act, Schedule 20 4(2)

The nominated Undertaker must after the removal of remains… a) within 12 months or such longer period as the Secretary of State may direct in relation to the case….bury them…cremate them…, or b) deal with them in such other manner as the Secretary of State may direct.’

By producing the requirements in this way, the Act set the bar but left the option open for alternative arrangements if the project circumstances required it. The 12 month deadline, for example, once the scale of the grounds was better known, seemed to be at cross purposes with the requirement of the Heritage Memorandum to carry out a full programme of archaeological analysis of buried human remains, a task which can often take up to 12 months, and can usually only be carried out on an entirely removed assemblage of remains: in practice, it will have taken nearly four years to remove the entirety of St James’s burial ground, by which time 75% of them would have had to be reburied in the 12 month timeframe.

The appropriateness of archiving

Another Heritage Memorandum requirement is to keep an archaeological archive of significant finds, including, potentially, human remains. This is not an approach that the CofE supports in principle. As described above, while the Act is primarily clear that human remains over 100 years old must be reburied, a sub clause allows for remains ‘to be dealt with in a manner other than reburial’ with permission from the Secretary of State. In order to meet the requirements of the Heritage Memorandum and expectations of heritage stakeholders, this was always going to have to be sought – human remains over a certain age, and not subject to other religious or cultural requirements, are frequently retained in museum stores or in other institutions for future research. The CofE is clear that human remains, if they have to be removed, are returned to the conditions in which they were buried – in consecrated ground. However, if remains are kept in a consecrated space specially created and maintained by the CofE, then this an acceptable alternative to reburial (APABE 2017, p.11). This provides the context for one of HS2’s Assurances to St Pancras Church to explore whether the crypt could be used as a proposed reburial site (Assurance to St Pancras Church, 26/08/2016[12]). A feasibility study for the crypt of the church was carried out by HS2 in 2017, showing that capacity at the site, considering the scale of the potential archive, was not suitable. This challenge has led to a second strand of the reburial programme to investigate the possibility of creating a Church Archive of Human Remains elsewhere (see below).

Cost and value for money

There are not unlimited options, particularly within and around major cities, for reburying large populations of human remains. For CofE remains, this also had to be consecrated ground. With additional requirements of being located ideally within the Parish, within the Diocese, or at worst within the geographic region, and with extra requirements such as for the reburial of coffins (some with environmental considerations) or grave markers, the market available to HS2 was relatively limited. Furthermore, some grounds excluded themselves from consideration for logistical, management or local political reasons.

There is no cost comparison for an exercise of this scale. On smaller scales, in different locations and with different governing parameters there are standard rates and accepted fees. Where to start with negotiations for reburying over 20,000 sets of human remains in a single location? How could reasonableness be ensured? This problem manifested itself as conversations started with potential reburial grounds – some suppliers saw the project as an opportunity to pursue their own aims at high prices. Approaches could not be kept anonymous, with the scale and nature of the work revealing HS2’s identity and possibly raising expectations of involvement in a high-profile project. Hidden costs also emerged early in negotiations – the price of maintaining a burial plot to ensure privilege of burial for up to 100 years. Who would pay for the upkeep and at what cost? The answers seemed to differ across regions and authorities and depending on the financial maths applied by different suppliers in their cost calculations.

Families and the famous

In the background to the reburial programme, which for the most part concerned rebuying or relocating individuals buried over 100 years ago with no living relatives or any particular interest in the precise destination of their remains, two individuals buried by the Church of England came to the attention of the public. Matthew Flinders (1774-1814), the Royal Navy explorer who first circumnavigated and named Australia in the years before colonisation, was known to have been buried in St James’s Gardens, and his surviving relatives were interested in returning his remains to the family Church in Donington, Lincolnshire. The government of Australia also expressed an interest in the remains in 2019. Lord George Gordon (1751-1793), the British politician known for the 1780 Gordon riots, and for his later conversion to Judaism, was also buried in St James’s Gardens, so the question was raised as to the faith in which he should be reburied. HS2 also received enquiries about other individuals, including some relatives, buried in St Mary’s Churchyard. Church of England policy is not to remove any individual from the original congregation within which they were buried for any reason, unless a mistake has been made. The HS2 approach of treating all human remains with dignity and respect, regardless of their place in history, politics, faith or reputation, had to underpin the management of these individual situations.

Design Approach

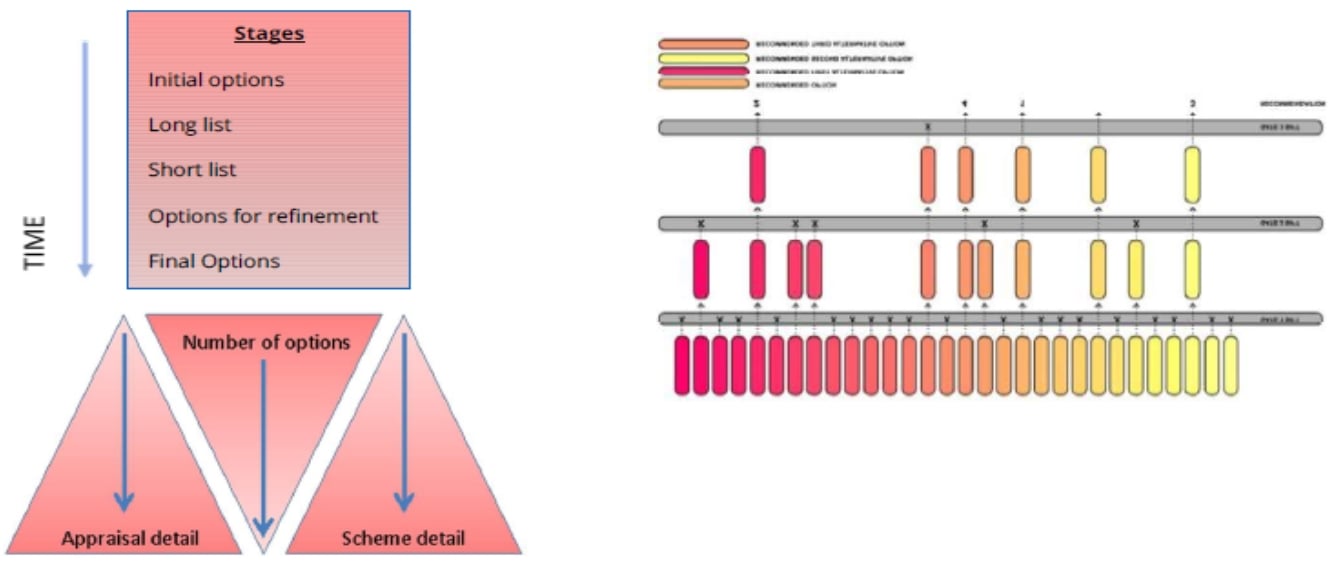

The ‘SIFT’ process

HS2 uses their ‘Route Development Procedure’ (including a process of ‘Sifting’ options) to guide design optioneering – whether for route selection, the location of new stations or environmental remediation proposals. The Sift process has guided the decision-making for reburial site selection for the large CofE burial grounds on Phase One. The Sift process is an evidenced based iterative approach, where a common set of criteria and principles are applied to a diminishing range of options. The Sift is a structured and evidenced methodology for capturing the requirements of the project, the responses of stakeholders and eventual decisions. Technical and commercial decision makers are involved throughout and buy into the process at each stage. In addition to legal and technical criteria, considerations of land use, location, programme and availability can be captured. The Sift process for reburial has also been able to accommodate the possibility of retaining a proportion of the human remains from any location in a Church Archive (see above), as well as for reburial site selection. The Sift captures risks and challenges, so that assurance is an integral part of the site selection process.

Optioneering within the structure provided by the Sift was carried out within the supply chain, including specialist sub-contractors to carry out site surveys to provide greater levels of detail as the Sift progressed.

The process was applied in three rounds for each of the large burial grounds (similar to the station selection process in Figure 5) followed by commercial papers to obtain high level agreement within HS2 prior to Commercial Agreements with third parties.

For the large burial grounds, the Sift process could start as soon as archaeological surveys could provide an acceptable level of confidence in the numbers and likely nature of the remains to be reburied from an individual burial ground, as well as their likely significance, to establish the proportion of remains suitable for possible archiving. The Archive options within the SIFT reflect CofE preference for keeping buried congregations together, and within region, as far as possible (so the idea of an ‘HS2 Church Archive’ for the entire route was not considered). Archive options were kept live for the duration of discussions with stakeholders about the emerging research potential of the remains. For the smaller grounds, and non-CofE grounds, the size of assemblages will only be known once fieldwork is complete, and the appropriateness of retention or reburial known once significance has been fully assessed.

Assuring compliance with the Act

The reburial programme could not be assured without further Direction from the Department for Transport in accordance with the Act (see above). Two Directions were sought, the first to allow the retention of remains for 60 months if of academic interest (to enable the Heritage Memorandum-required archaeological research to be carried out), and for the permanent retention of remains in a suitable place if considered to be of value for longer term research. A second Direction was sought to allow for remains not of academic interest to be reburied within an extended timeframe of 24 months, to allow for the complex process of site selection required, and in consideration of the scale of the challenge.

A sequence of reporting (Schedule 20 Section 8) was agreed with the office of the Registrar General, to reflect the new timeframe. Removal of human remains is reported every 12 months in accordance with the Act with details of where remains are temporarily stored, and a schedule of reports agreed for providing details of final locations of the remains within the new 24-month and 60-month timeframes.

Assuring Compliance with the EMRs

To comply with the legal Undertaking with the CofE, and with the requirements of the Heritage Memorandum, engagement with the Archbishops’ Council and Historic England were programmed into the Sift process. The CofE provided legal advice on the acceptable parameters for retaining human remains out of the ground for research (in Church Archives), as well as suggestions from the Dioceses for options to consider in the SIFT, for both burial and archive. Historic England, having stated a preference in consultation to retain a sample of human remains above ground for future research, were consulted on the stages of the Sift as they related to Church Archives, and will continue to be consulted on the future of human remains destined for non-CofE locations as the programme is extended for Phase One, and for future phases of the project.

Commercial approach

Negotiating a price for the reburial of large numbers of human remains is not simply a matter of multiplying the cost of burying one person in normal circumstances by several thousand. The scale also adds complexity to issues of reputation, cost and risk. Four aspects of the commercial approach to the reburial programme stand out:

- the importance of dealing from the outset with the highest level of any organisation owning or managing a burial ground, with experience at the right scale, and the legal standing to sign the required Non-Disclosure Agreements;

- the range of skills and knowledge required to undertake any such negotiation, including knowledge of financial structures and legal frameworks as well as of statutory requirements, land values, legal and environmental issues (dictating how deep burials could take place and effects on the water table, for example);

- the importance of engaging commercial (as well as contractual) skills from the outset of the process – these commercial skills were employed within the supply chain if the Contractor was the negotiating party, in others the responsibility lay with HS2 commercial and Agreements teams to support the process;

- the necessity for clear, neutral baseline information for individual options (for Sift Stage 1), including information about approach to costing, who would be responsible for the reburial work (the site or HS2), and commercial risk, prior to any negotiation.

In particular, this last issue of costing and formulating a price was complex and subject to different approaches across Phase One. The opportunity cost of providing the area for HS2 burials – the revenue that would be lost by the burial ground over 100 years from selling that area as individually sold plots with exclusive right of burial – has formed the basis for this cost calculation, developed in different ways by individual suppliers. A secondary cost to be negotiated, also subject to different methods of possible calculation, was that of maintaining the burial plot for the 100 years of exclusive burial. This maintenance necessarily includes maintaining reinstated landscaping and a memorial structure. HS2 encountered a full range of ideas from burial grounds as to how this aspect of reburial should be priced and funded – from a lump sum, calculated with compound inflation over 100 years, to waived completely. Such was the difficulty of agreeing this secondary cost the possibility of negotiating separate agreements for reburial and for maintenance was mooted on one occasion in the programme. Agreement of a Maintenance Grant, with funds (calculated using standard rates and with inflation discount) to be administered by parties outside of HS2 for the term, has provided the solution to this complicated and unusual issue where needed so far.

COVID 19

In March 2020, with the reburial programme underway in Birmingham, and negotiations at a key point with suppliers in London, the UK began the lockdown period to contain COVID 19. As a result of restricted access to reburial sites and diminished availability of staff at supplier end, the reburial timeframe was put at risk. Initially, concerns extended even to the capacity of the selected grounds to take the HS2 burials if virus deaths were to exceed expectations.

Risk assessment considered mitigation in relation to (temporary) reburial location, timing of work, site work safety and stakeholder response times.

Summary of Outcomes and a structure for the future

The results of the reburial programme as they stand in August 2020 are summarised in Table 2. By its nature, the programme will be ongoing as long as new ground is being broken on the Project and human remains are recovered, but burial of the largest proportion of human remains likely ever to be in HS2’s care is now underway, those from Park Street at Birmingham’s Witton Cemetery (Figure 6), and from Euston at Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey

Apart from delivering within required budgetary limits and controls, within the parameters set by the Act and in accordance with HS2’s other requirements, the programme so far has established the framework for future stages of reburial on Phase One and potentially future phases of the Project:

- the Route Development Procedure (Sift) has been established as the means by which options for reburial are compared and captured;

- 24 months has been established as the timeframe for reburial of remains not required for academic study – this timeframe allowed for extended negotiations for Phase One, leading to substantial cost savings for the project;

- 60 months is the new timeframe for reburying or dealing otherwise with remains of academic interest on Phase One – this will allow HS2’s own research programme to be delivered, but also external academic partners to engage with the assemblage of human remains from Phase One. These potentially large-scale academic projects will produce scientific studies of these populations and their environment, including epidemiological work and research into disease transmission;

- the possibility of retaining human remains of particular historic interest (especially those more than 1000 years old) in a manner other than reburial (such as in a museum, or Church Archive if CofE) – for ongoing research, has been agreed in accordance with the Act;

- The Directions acquired from DfT on Phase One have been considered in discussions of the Act wording and legal agreements for Phase Two of the project;

- a close working relationship has been established with the Archbishops’ Council of the CofE, a key Stakeholder, and through them with the Dioceses involved in the work;

- channels of communication are open with the DfT on the burial grounds work, with ongoing liaison over reburials programming including the management of C19 risk; and

- reporting structures are in place with the General Register Office for reporting and confirming the reburial locations of all individuals removed by the Project, for families and researchers to access in the future through the National Archive.

Matthew Flinders’ story continues – following application to the Archbishops’ Council for removing Captain Flinders’ remains from the rest of the population from St James’s Gardens, a response was received by the Flinders family that the Archbishop of London would have no objection to the move to Lincoln, and at the time of writing, his remains could go to the family’s local church at St Mary, Donington. How the family and the Diocese in Lincoln proceed is still to be decided. Lord George Gordon was never found: his burial plot at the far north-west end of St James’s Gardens, in the ‘Upper Ground’ was found to have been significantly disturbed by the building of a boiler house and diesel tank in the 1960s. This had removed several rows of burials and the funerary monuments buried with them, their final resting place unknown.

| Burial Ground | Reburial site – for remains not of academic interest | Archive location – for remains of academic interest | Numbers reburied /in process of reburial | Timeframe | Stakeholder involvement | Public engagement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

St James’s Gardens, Euston, London |

Brookwood Cemetery, Woking (once served by the Necropolis Railway from Waterloo) Burial site of London Parishes including those removed from St James’s Chapel, in the burial ground in 1960. |

Archive Optioneering complete, commercial process in progress |

15,000 |

Reburial taking place within 24-month legal time limit, 60 months for remains of academic interest. |

Final option approved by C of E. HS2 will work with the Diocese of Guildford to design a memorial and to organise commemorative services. Historic England involved in Archive discussions. |

Announcement August 2020. The story of Brookwood and continuity of use for London burials, expected to engage public interest. |

|

Park Street Gardens, Birmingham |

Witton Cemetery, Birmingham Urban cemetery, offering multi-denominational burial grounds. |

Archive Options still live |

6,000 |

Reburial taking place within 24-month legal time limit, 60 months for remains of academic interest. |

Final option approved by C of E. HS2 will work with the Diocese of Birmingham to design a memorial and to organise commemorative services. Historic England involved in Archive discussions. |

Announcement February 2020. Further local engagement to be undertaken in conjunction with commemorative services. |

|

St Mary’s Churchyard |

Options still live |

Archive Options still live |

N/A |

Reburial to take place within 60 months of first removals – this entire population is likely to be of academic interest. |

Options approved by C of E, further communication to be undertaken with Diocese and individual sites. Historic England to be involved in Archive discussions. |

Engagement with local Parish and community ongoing. |

|

Freeman Street Baptist burial ground |

Witton Cemetery – Baptist Ground |

N/A |

>10 |

Reburial taking place within 24-month legal time limit. |

Baptist Union engaged and will be involved in the reburial process |

Announcement February 2020. Further local engagement to be undertaken in conjunction with commemorative service. |

|

Non-Christian burial grounds, remains over 100 years old |

Remains currently being held by specialist archaeological contractors pending post-excavation assessment of significance. |

Archive Options still live |

N/A |

Archive/reburial approach still to be decided. |

Local Authorities to be engaged over future location of remains of academic interest. Historic England to be involved in Archive discussions. |

Further engagement to be undertaken within programme of post-excavation analysis. |

Acknowledgements

Ailsa Waygood (HS2), Helen Wass (HS2) and Michael Court (HS2). Also Andrew Harris (Fusion), Caroline Raynor (CSJV) and Mary Ruddy (LM/WSP).

References

[1] HS2 Phase One Environmental Statement.

[2] HS2 Phase One Historic Environment Research and Delivery Strategy (HERDS).

[3] APABE, 2017 Guidance for best practice for the treatment of human remains excavated from Christian burial grounds in England, p5, 6.

[4] Burial Act 1857, Section 25.

[5] Thomas C, 2004, Life and death in London’s East End: 2000 years at Spitalfields, MOLA

[6] Hartle, 2017, The new Churchyard: From Moorfields Marsh to Bethlem Burial Ground, Brokers Row and Liverpool Street, Crossrail Archaeology

[7] Emery & Wooldridge, 2011, St Pancras burial ground: Excavations for St Pancras International, The London terminus of High Speed 1, 2002-2003, Gifford

[8] Buteaux, 2003, Beneath the Bull Ring: The Archaeology of Life and Death in Early Birmingham, Brewin Books

[9] Cool, H and M. Bell, 2011, Excavations at St Peter’s Church, Barton-upon-Humber, Archaeology Data Service. Published: https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/bartonhumber_eh_2010/

[10] The High Speed Rail (London to West Midlands) Act 2017, Schedule 20 Burial Grounds.

[12] HS2 Phase One register of undertakings and assurances.

Organisations with guidance on the treatment of human remains:

The Advisory Panel on the Archaeology of Burials in England (APABE)

Department for Culture Media and Sport (2005)

British Association of Biological Anthropology and Osteoarchaeology

Peer review

- Mike CourtHistoric Environment Lead, HS2 Ltd