Designing with landscape maintenance in mind

The HS2 project is delivering built infrastructure and natural environments on an unparalleled scale. The project affords a once in a generation opportunity to deliver nationally significant infrastructure that will respond to local landscape character and demonstrate an innovative and environmentally-sensitive design approach.

The project has been developed to minimise it’s impacts on the surrounding environment through high-quality design that is sensitive to landscape character, and where possible make a positive and contextual contribution by delivering environmental enhancements.

To achieve such success, it is important to consider the management and maintenance requirements early in the design process to create efficiencies in the whole life cycle of the scheme, and to enable delivery of landscape-led resilient low-maintenance systems which both enhance and create habitats. The management and maintenance of these landscapes will be key to the long-term success of the project to ensure the specific intent of each designed element is successfully safeguarded and delivered in line with the HS2 Design Vision.

This paper investigates the design parameters related to the operational maintenance of the railway and the associated landscapes and habitats by looking at best practice guidance and lessons learned from equally significant infrastructure schemes. Furthermore, it will explore how collaborative multidisciplinary design which puts landscape setting and context at the forefront of all design solutions will balance functional requirements, reduce embodied carbon, aid landscape and visual integration, maximise environmental and biodiversity gains, and deliver long-lasting landscape and ecological legacy.

Introduction

The HS2 design proposals have been developed to minimise their impacts on the surrounding environment and, where possible, make positive landscape and ecological contributions to it. This has been achieved by taking both environmental and engineering factors into account during the design stages.

In line with the HS2 Design Vision [1] to ‘design for a sense of place’, local identity, landscape regeneration and environmental enhancements will all be considered as many new places and spaces are created, as well as the restoration of existing natural environments that interface with the line of the HS2 route.

Landscape, and the use of land near the railway, has an important role in reducing the effects of the design proposals, as well-designed and well-considered landscapes can provide a broad range of environmental mitigation such as visual and noise screening, and replace habitats that are lost as a result of the construction of the project. This will lead to the creation of many different landscape typologies which will be delivered in line with the principles of the Landscape Design Approach [2], to conserve, enhance, restore, and transform the landscapes and communities which interact with the HS2 proposals. These landscapes and habitats need to be designed with their long-term operational maintenance, and the long-term landscape legacy in mind to help release their full potential and maximise habitat biodiversity value.

The design, implementation and future management of the landscapes associated with the route will demonstrate HS2’s commitment to the natural world. HS2 has a positive environmental rationale and will use design to help deliver imaginative, appropriate and environmentally sustainable solutions. Given these commitments, it is important to consider the management and maintenance requirements of each designed asset early in the design process to ensure that the specific design intent of each element is successfully preserved.

What are we maintaining and why?

The management and maintenance requirements for all areas of habitat and landscape shall be carried out in line with the following strategic landscape management principles:

- ensure that management and maintenance is undertaken to ensure the safe and resilient operation of the railway;

- ensure maintenance and management operations establish the habitats to meet the requirements set out in the Environmental Statement (ES) [3];

- ensure maintenance of planting character consistent with that of the surrounding landscape thereby aiding the integration of HS2;

- achieve healthy habitats which contribute to a no net loss to biodiversity;

- ensure that planting is maintained in a productive and economical way;

- ensure that new landscapes and habitats are maintained to maximise multi-functionality;

- ensure that management and maintenance is undertaken to respond to the passenger experience, including maintenance of view corridors;

- and identify and meet all legal obligations regarding management and control of flora and fauna and protected and notable species.

Environmental impacts, including the visual impact of changes to existing vegetation and new landscape planting, are assessed prior to and during the Hybrid Bill stage and are reported by means of an Environmental Statement (ES) [3]. The Phase 1 ES [3] identifies the likely significant effects that will arise from the construction and operation of the project and identifies a range of mitigation measures that need to be implemented to reduce or eliminate these reported effects.

All areas of habitat and landscape developed in response to the ES design will have a defined set of primary, secondary and (sometimes) tertiary objectives to mitigate environmental impacts. The design of these areas needs to be safeguarded by embedding the management and maintenance requirements into the designs to ensure their long-term legacy and success.

Whether ownership of these habitats and landscapes is retained by HS2 or passed to a third party, the commitments set out in the ES [3] need to be followed to ensure that the elements of the scheme continue to fulfil their intended function (e.g., ecological compensatory habitats, visual screening, landscape integration etc.), and in all instances, ensure the successful mitigation of significant effects arising from the construction and operation of the project in perpetuity.

It is important to consider the specific management and maintenance requirements early in the design process, so the designs can be developed with due consideration given to the ease of maintenance operations which are less intensive, economically sound, and which overtime lead to the creation of rich biodiverse habitats. For example, the design of the landscape within the rail corridor can include grassed areas with minimal depth low–nutrient soils which will encourage slow–growing grassland species, reduce embodied carbon and maintenance requirements, while also enhancing biodiversity value.

This approach is illustrated in figure 1 and figure 3 where extensive swathes of grass seeding including oxeye daisies (Leucanthemum vulgare) were sown trackside and to the cutting slopes along the HS1 rail corridor. This approach created low-maintenance grasslands that delivered valuable and attractive habitats and provided seasonal interest that would be visible to passengers when traveling on the trains.

The A345 Weymouth Relief Road in Dorset (refer to case study 1) adopted a similar approach based on a limited topsoil soils structure which was sown with native perennial wildflowers that were left to establish and diversify naturally. The approached delivered both construction benefits (reduced earthworks strategy via limited topsoil requirements and simple seeding applications) and operational savings (no routine maintenance leading to reduced resource, carbon, and costs), as well as delivering significant biodiversity gains.

Successful functioning biodiverse landscape and ecological design is achieved through the development of long–term strategic management plans (primarily led by Landscape Architects and Ecologists) that are informed by the design process, and which are developed and drafted by the design teams as the designs mature. It is important that these management plans reflect all operational and functional requirements of the railway, as well as the long-term management and maintenance requirements of the various landscapes and habitats. Incorporation of these critical functional design criteria will be key to successfully delivering the HS2 Design Vision [1], and to ensure delivery of the key themes of the HS2 Sustainability Approach [4] to provide social, economic and environmental benefits through the design, construction and operation of the railway (see figure 2).

The areas of landscape which are required for the operation and management of the railway can be categorised by their proximity to the track and their logistics and land use requirements. Each of these areas necessitates a differing management strategy to facilitate a safe and resilient operational railway, while ensuring that the varied landscapes and habitats are maintained to maximise multi-functionality in a productive and economical way.

The landscapes and habitat areas that are being created as part of the proposals can broadly be described as follows:

- areas of landscape treatment requiring management, maintenance and monitoring during the construction phase (including temporary works);

- areas lineside of the security fence where works could occur at a safe distance from moving trains (with maintenance works primarily to be carried out during daytime and within operational hours);

- areas lineside of the security fence where works would need to be undertaken outside of passenger train operating hours;

- areas between the security fence and boundary fence that would remain within ownership of HS2 Ltd;

- areas of landscape outside the boundary fence where the body responsible for ongoing management/maintenance is yet to be determined; and

- areas of vegetation on third party land that could influence the operation of the railway.

These areas, and the associated maintenance activities, are further detailed in the Employer’s E16 Information Paper ‘Landscape Maintenance Policy’ [5], and the Employer’s E26 Information Paper ‘Indicative periods for the management and monitoring of habitats created for HS2 Phase 1 [6].

Operational maintenance design parameters

The provision and management of lineside vegetation requires careful consideration in order to prevent safety issues arising, to minimise potential operational maintenance issues (such as ‘leaves on the line’ or overhanging branches), and to avoid unnecessarily onerous maintenance liabilities.

HS2 is designed to operate without impairment during normal running hours and certain planned maintenance activities may be restricted to night‐time maintenance windows. This means that any maintenance of lineside vegetation on or near the line will need to be undertaken outside of operational hours, and this will need to be addressed in the methodology, planning and risk assessment for any such operations.

Wherever reasonably practicable, the landscape designs should minimise the need for routine maintenance of lineside vegetation within the HS2 security fencing (especially that near the line). This could be achieved through the specification of low-maintenance habitats in these sensitive areas (see both case study 1 and 2 for examples of this type of design approach), and through the careful consideration of the optimum position of security fencing.

The positions of security fences should also be determined with a view to minimising the operational footprint of HS2 and maximising the proportion of areas that can be maintained unimpeded outside of the secure boundary during operational hours with no risk to the operatives (see figure 3). The areas outside of the secure boundary which are not required for operational purposes could be subject to future land disposal or hand back agreements, depending on the scenario, to further reduce HS2’s long-term maintenance requirements.

HS2 Ltd has committed to treat the health and wellbeing of those constructing, operating and maintaining the HS2 railway, and those interacting with it on parity with all other associated safety risks. In managing health and safety in the design and construction process, and in fulfilling the duties of The Designer as set out in the Construction (Design and Management) Regulations 2015 [7] (CDM), the designers must apply the general principles of prevention to identify, control and/or design-out risk as reasonably practical.

When designing lineside vegetation, health and safety risks associated with maintenance activities shall be identified and where possible eliminated. This applies to foreseeable risks occurring during construction, operation and critically also during the ongoing maintenance and management process which should all be avoided, reduced or controlled as appropriate.

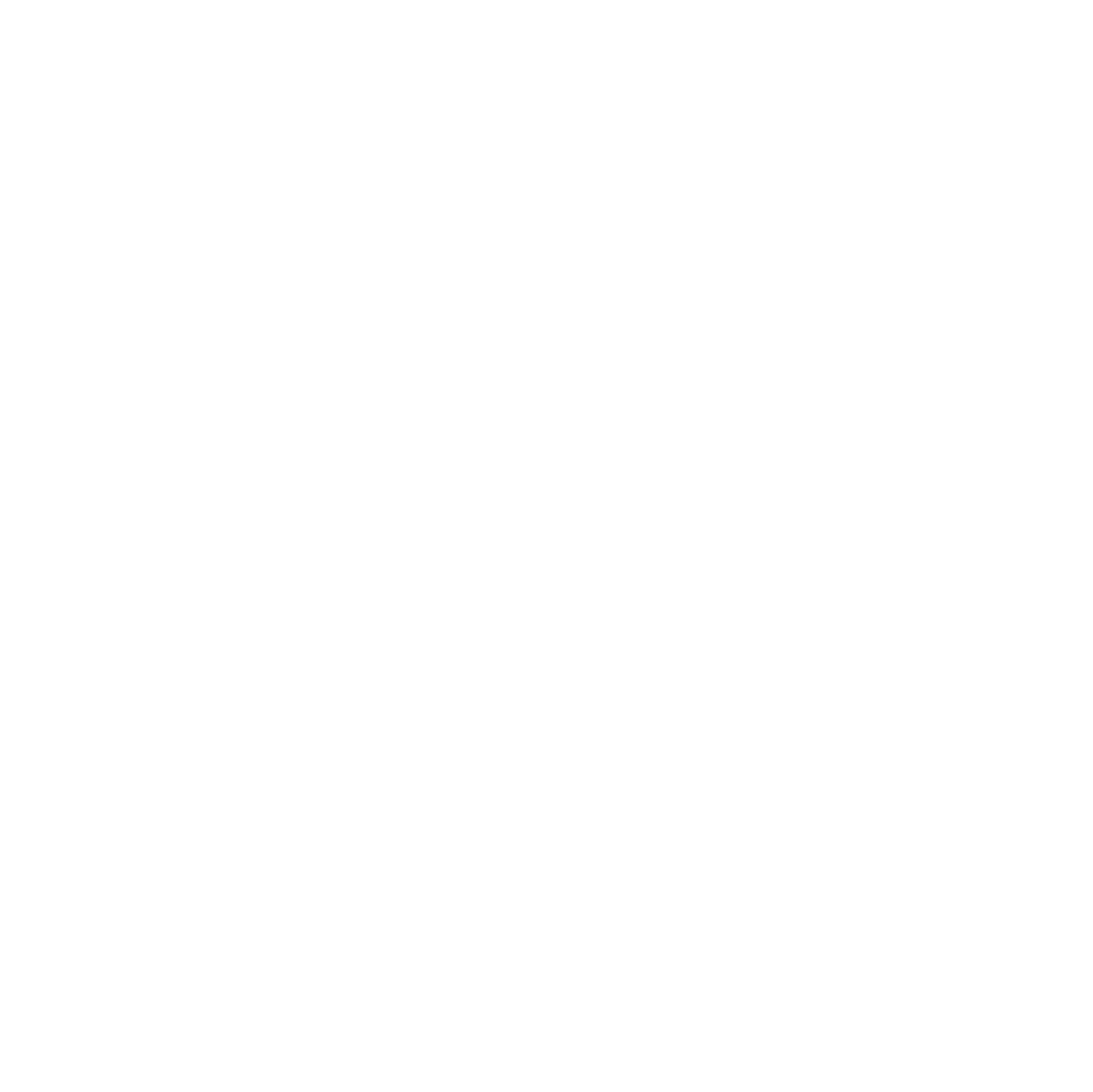

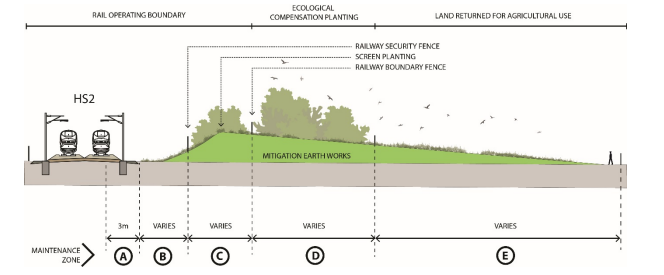

It is critical that planting will be designed to minimise risks to the operation of the railway that may arise from falling leaves, root damage and high winds breaking branches or the felling of trees in the vicinity. In practice, this means a controlled vegetation zone, called the ‘zone of influence’, will be established along the HS2 operational railway corridor, within which the height of vegetation and trees will be restricted (this zone of influence is represented by the areas A, B and C in figure 4 and in figures 5 and 6 below). Depending on the fencing arrangement, the ‘zone of influence’ may extend beyond the HS2 boundary fence for operational and/or maintenance reasons, and as such may have implications for third‐party land beyond the HS2 boundary fence.

Note areas for ‘ecological compensation’ are not required on all parts of the route.

- Area A* to be free of all vegetation in order to meet operational railway requirements.

- Area B* to be free of tree planting.

* areas A and B = the zone of influence.

- Area C where tree planting is to be height limited.

- Area D land for ecological compensation planting – no height limitation.

- Area E land returned to agriculture or other locally appropriate use.

The ‘zone of influence’ is defined as an area offset from the overhead catenary system (OCS) masts with implications on the design and the provision and maintenance of lineside vegetation (see figure 5). The ‘zone of influence’ has a minimum offset of 10 metres from the outermost OCS mast but shall be extended as far as necessary if the expected height and spread of the largest trees would otherwise intersect with a line drawn at 45° upwards from the base of the OCS mast.

Only certain considered planting which will aid bank stabilisation, will require limited topsoil depths, will require infrequent maintenance or is low growing and broadly self-maintaining, and which will continue to diversify over time can be provided within the ‘zone of influence’ (see case studies 1 and 2, and examples of planting setbacks in figure 6). Equally some species are not recommended or are to be avoided within the zone of influence in light of their specific characteristics (e.g., fast growing species, trees that have vigorous growth characteristics, are invasive, or are prolific regenerators, prone to become unstable, are of a high-water demand, can become too high, suffer from dieback, trees that bear fruit, and trees that have known leaf fall problems).

The design of the landscapes within the operational rail corridor (i.e., within the HS2 security fence – zones A and B in figure 4) should be designed to reduce the need for frequent maintenance. Zone A will be kept free of vegetation at all times in order to meet the railway’s operational requirements, and there will be no tree planting within zone B (unless this is deemed to be an important environmental requirement). Instead, grassed areas (see figures 1 and 7) with low nutrient soils will encourage slow-growing species rich habitats, which will promote biodiversity gains helping to shape the wider HS2 Green Corridor initiatives [8 & 9] while also facilitating reduced maintenance requirements.

The HS2 design approach has been developed to maximise the amount of land that is to be returned to functional agriculture (or other locally appropriate uses) where not required for operational reasons, or for ecological compensation, with a view to minimising the amount of land to be permanently owned by the railway operator. Where land is surplus to requirements post-construction, earthworks in many locations along the route will have shallower slopes (zones D and E in figure 4) to allow land to be returned to a locally appropriate use, aid earthworks integration, and help respond to local landscape characteristics. This approach will also limit the long-term operational maintenance footprint of the railway corridor and will help reduce associated ongoing maintenance costs.

When designing for areas within the operational security boundary (within the zone of influence), areas of soils and grassland on cuttings and embankments should be designed so that they ensure effective erosion control and stabilisation. Suitable planting species shall be selected to ensure that maintenance requirements are sustainable and appropriate, and that the establishment and long-term health of the grassland can be ensured with the growth not exceeding the maximum heights and spreads within the parameters identified within the ‘zone of influence’.

Existing vegetation and new planting areas beyond the operational railway boundary / security line shall also be maintained to ensure that growth does not encroach into the ‘zone of influence’. Subject to the normal risk assessment process, it should usually be possible to undertake routine maintenance of grassland and planting areas between the HS2 security and outer boundary fence lines during the working day.

Due consideration needs to be given to the access requirements to ensure access to each area requiring maintenance is available without needing to pass through the operational railway land (inside the HS2 security fencing), or adjacent neighbouring land parcels outside of HS2’s control. The lack of a defined maintenance access strategy, and dedicated maintenance access routes, could severely restrict the logistics of the relevant planned maintenance activities.

The guiding principles are that the HS2 assets should be accessible by a safe and appropriate route suitable for the maintenance (including inspection and replacement of assets), operational or emergency task. The term ‘HS2 access’ refers to any private route leading to an HS2 facility or site used for operational, maintenance or emergency reasons (or any combination thereof). Where feasible, facilities provided for operational, maintenance or emergency reasons should be co-located to optimise provision of permanent HS2 vehicular accesses, and where feasible, temporary accesses provided for construction purposes, for example mass haul routes, should be located at points where permanent HS2 vehicular accesses are required. As a result, the temporary route can be converted to a permanent access leading to less impacts on the surrounding environment and local community during construction.

Access also includes alterations required as part of the HS2 scheme to existing private routes to property, businesses and farmland (known as accommodation works), as well as new access routes to HS2 infrastructure and facilities. HS2 vehicular accesses and accommodation accesses may also be shared if practicable with the aim of minimising access interventions in the rural countryside which could have a negative impact. Public and private access routes associated with the HS2 scheme should equally be designed to integrate into the existing character of the area, through careful alignment and careful selection of appropriate materials in response to their context and intended use.

The hierarchy and different types of HS2 access are defined as:

- HS2 vehicular access (3.5m) – a surfaced (either paved or unpaved) access suitable for vehicular use provided between the road network and HS2 assets;

- HS2 maintenance access strip (3m) – a reasonably-level spatial allowance to allow HS2 staff to conduct inspection or maintenance activities using a four-wheel-drive vehicle;

- HS2 pedestrian access route (1.5m) – a pedestrian route to allow emergency access/egress or HS2 staff to conduct inspection or maintenance activities on foot, being either a spatial allowance only or a surfaced route; and

- HS2 lineside walking route – a pedestrian route adjacent to and parallel with the operational railway in open sections of the route (i.e. excluding tunnels), which allows emergency access/egress and/or HS2 staff to conduct inspection or maintenance activities on foot.

HS2 vehicular accesses shall be provided to all maintenance access points, unless the maintenance access point is located adjacent to a road. Parking for a minimum of two long-wheelbase vans shall be provided at all maintenance access points, either combined with that provided for other purposes, or separately (depending on site-specific usage requirements).

When placing gates, access routes and parking adjacent to roads (see figures 7 and 11), particular consideration shall be given to ensuring that all foreseen risks have been designed out in line with the principles of CDM [7] so that all health and safety risks are eliminated, and the design is safe for both operatives and road users. This applies to foreseeable risks occurring during construction, operation and maintenance in all seasons and weather patterns, particularly where long-term weathering could affect the safety of maintenance access and the safety of the associated maintenance activities (see figure 9 where safe access for maintenance equipment was not fully considered at the design stage).

Maintenance access strips shall be provided to all planting areas including planting on green bridges and areas provided for ecological or visual reasons (see figure 10). Maintenance access strips should extend in and around planting areas, and ecological mitigation ponds, so that they can be maintained in accordance with the planned landscape and ecology objectives.

Maintenance access points are locations where there is a gate in the HS2 security fence that allows for maintenance activities to occur within the operational railway. Additionally, they allow emergency access and egress in case of incident or accident. Maintenance access points are accessible by standard road-going vehicles and should have parking spaces provided.

There is no general requirement for a lineside HS2 vehicular access along the HS2 rail corridor, however, there may be situations where it is expedient to use short lengths of HS2 vehicular access beside the line to enable vehicles to reach specific facilities (e.g., tunnel portal rescue areas) or to connect nearby facilities together (see figure 11). In addition to catering for inspection vehicles and maintenance plant and equipment, consideration needs to be given to the means of getting water to site should the need arise.

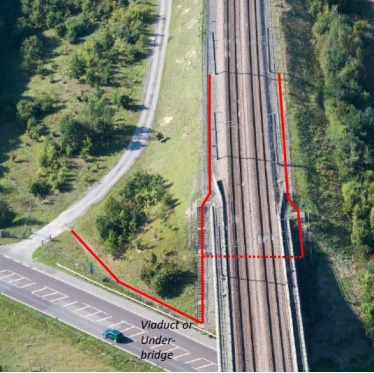

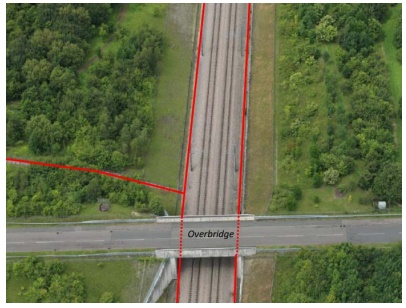

For viaducts, vehicular access and parking provision shall be provided within 200 metres of each abutment, and at or near track level where this is reasonably practicable (see examples illustrated in figures 8 and 12). Onward pedestrian access to the abutments should be provided to both sides of the railway allowing access to both abutments by a connected pedestrian walkway under the viaduct. A maintenance access strip shall be provided to, and run parallel along, one side of each viaduct.

HS2 vehicular accesses shall be provided to all maintenance access points, unless the maintenance access point is located adjacent to a road. Maintenance access strips should be 3 metres wide outside of the operational railway boundary to enable inspection and maintenance activities to occur either on foot, or by all-terrain vehicle. Where these accesses are located outside of the HS2 secure operational corridor, consideration should be given to how these routes can serve multi-functional purposes, for example cycling and walking routes, whilst also serving as a maintenance access.

A pedestrian access route shall be provided between the parking provision for the maintenance access points and the lineside plots with consideration given to the types of equipment operatives will be transporting on foot, and the distances required to walk from the parked vehicle to the associated worksites.

The pedestrian access route shall be clearly delineated and have a flat, low-maintenance surface. They do not have specific surfacing requirements and should generally be grass unless the local landscape character dictates another surfacing type. Consideration should be given to providing step-free inclusive pedestrian access as this could allow the use of wheeled devices (such as trolleys and wheelbarrows) when conducting maintenance activities. Associated access gates should be designed (located and sized) in line with the parameters of the elements to be accessed and maintained, and in line with the parameters of the appropriate maintenance machinery required to carry out the relevant maintenance tasks (see figure 13). As a preference, tasks should be undertaken by automotive methods to be effective and efficient as possible, to reduce the requirement of intensive manual methods, to avoid deployment of manual labour, and to reduce occupational health and safety issues to the maintenance operatives.

Lineside walking routes shall be provided along the length of HS2 on both sides of the railway for ‘off-track’ inspection and maintenance purposes, particularly where railway systems lineside cabinets and equipment are located. The lineside walking route shall be designed to be capable of accommodating fully inclusive access for users of all abilities and should adhere to the principles set out in the Employer’s D6 Information Paper: ‘Inclusivity Design Policy’ [10].

As with all aspects of the project, HS2 accesses should be sensitive to the unique patterns, subtleties and diverse character of the surrounding landscape in line with the HS2 Design Vision [1] to ‘Design for a sense of place’, and for landscapes that deliver multiple benefits for people, places and the planet to shape a sustainable and resilient future [2].

Designing for multi-functional biodiverse landscapes

Developing planting that is functional, sensitively designed, biodiverse, climate resilient and low-maintenance will be key to the success of the HS2 scheme. The process of developing the landscape designs along the HS2 route should intrinsically be a “designing with landscape maintenance in mind” process, with an ultimate goal of delivering multi-functional landscapes that deliver both operational and biodiverse value. A landscape-led approach requires a move beyond green design to regenerative design that values natural capital and delivers ‘hard working’ landscapes [2].

Understanding what land is needed for the operational logistics of the railway and what land is surplus to HS2’s operational requirements is paramount to the success of the scheme. The aim where reasonably practicable, is to reduce HS2’s operational and maintenance footprint, with land returned back to its previous use and/or other locally appropriate and beneficial third‐party uses depending on the scenario.

An understanding of permanent long-term land use is key in ensuring planting proposals are compatible with surrounding land uses, the landscape context, and their respective operational and management logistical requirements. Developing designs that consider future management with an onus on the ease of maintenance operations, sustainable practices and long-term economic goals [4], as well as the delivery of ecological and environmental enhancements are best achieved when integrated into the designs at an early stage. Future maintainers of the various habitats will need to be identified for every area of planting across the scheme, but if future maintainers for land outside of HS2’s permanent operational boundary can be ascertained early, these requirements can be identified, via a process of stakeholder engagement, and embedded into the design rational.

Areas of land, access to that land, and the associated land uses must fundamentally be designed to meet all the HS2 operational railway requirements. This means ensuring the successful maintenance provision of all vegetation within the HS2 lineside boundary, ensuring compliance with the parameters of the ‘zone of influence’ and ensuring any risks associated with planting in proximity to the rail corridor are designed out.

Other operational maintenance activities include maintaining the integrity of security fencing to preserve protection to the operational railway, maintaining clear line of sight for signals in depots by ensuring vegetation does not obstruct views, avoiding conflict between vegetation roots and underground services, maintaining clearance of ditches and watercourses associated with operational drainage of HS2, ensuring maintenance of all HS2 vehicular accesses (including verges and visibility splays), pedestrian access routes, maintenance access strips and lineside walking routes, and equally ensuring the maintenance of public rights of way (PRoWs) crossing HS2 land which can help facilitate the publics interaction with the project and enhance the user experience.

Defined access and maintenance strategies should be drawn up early in the design process (in parallel with the fencing strategy) to ensure that a clear and connected structure of HS2 accesses (vehicular accesses, maintenance accesses, pedestrian access routes and lineside walking routes) provide full connected and inclusive coverage to the HS2 assets and habitats which require inspection, management, maintenance and monitoring.

Accesses should also avoid the severance of existing adjacent land due to their alignment and should limit disruption to landscape features and working land parcels where possible. The aim should be to ensure the continuation of existing uses, and to limit disruption to existing habitats such as existing woodlands and grasslands, and to limit damaging ecological connectivity.

Landscapes shall be designed with consideration given to the health and safety risks of future management tasks in line with the principles of CDM [7]. This shall include safe access to sites and the construction of gentle slopes where reasonably practicable to allow the maximisation of automotive maintenance methods rather than manual processes (see example of typical maintenance equipment in figure 13).

All maintenance access routes passing through boundary fences, security fences and/or noise barriers shall include gates of sufficient width to permit access (step free where achievable) by landscape maintenance machinery to each plot or worksite with due consideration of the kit required to each location with appropriate access (see figure 9 for an example of poor access). Equally the size of maintenance plots and the planting designs should be arranged to be as manageable as possible, so maintenance can be carried out in an economical way over larger areas with speed and efficiency whilst preserving the landscape and ecological characteristics (see figure 14).

This process is aided by considered landscape design which looks to form manageable landscape maintenance parcels, and manageable habitats of similar landscape typologies, which where practicable require similar maintenance regimes. For example, larger areas of grassland which can be maintained by larger mowing equipment (see figure 15), avoiding smaller plots of land which are hard to access or do not allow enough space (i.e. between fences or behind errant vehicle protection – see figure 9) and would necessitate manual maintenance, and avoiding awkward shaped habitats which require labour intensive maintenance methods.

Design teams must consider how landscape led contextual designs can reduce management requirements and deliver wider value through the delivery of resilient and low maintenance natural systems. For example, the provision of swales in favour of typical engineered drainage solutions can provide less maintenance dependent systems, add biodiversity value, and reduce the need for hard built engineered solutions, reduce construction activity and the associated imbedded carbon.

Equally, the design and specification of landscape materials and features should look to maximise the use of sustainable products where practicable, with durable longer life materials, ideally locally-sourced or made with recycled components favoured and justified on a whole‐life value basis. Across a number of the Phase 1 early works sites, Fusion (one of the Phase 1 early works contractors) specified recycled cardboard tree guards (see figure 15) which offered high performance and are biodegradable in place of traditional plastic tubes. The use of these guards takes plastic out of the environment and reduces costs and emissions as there is a reduced need for waste collection and treatment.

Grasslands and meadows should be designed to enhance the ecological diversity of local environmental conditions and promote visually-attractive, low-maintenance landscape settings. Flower–rich grasslands form important multi-functional landscapes and are vital habitats for bees, butterflies and other wildlife, as well as helping to make soils secure, manage water, prevent flooding and sequester carbon. Where appropriate, designers should target the provision for UK BAP priority habitats [10] which will support the creation of environments appropriate for the UK priority species [11] such as a range of birds, mammals and invertebrates (see figure 16 and case studies 1 and 2).

With the abundance of grassland which is to be included within the HS2 railway corridor and associated landscape areas, including within urban settings, a wide range of grassland types will be incorporated to reflect the different local environmental conditions along the route and support a wide range of biodiversity and ecology. The opportunity should be grasped to utilise the scale of HS2 to deliver a meaningful increase in biodiverse grassland for the UK (see figures 1, 7 and 17 for examples of successful grassland planting).

Variations in management techniques (for example variations in mowing heights and in mowing timings) will create a diversity in habitats capable of supporting a diverse range in species. Oxeye daisy grass seed mixes have been a particular success along the HS1 route (see figures 1, 7 and 17) and resulted in significantly reduced mowing regimes. The incorporation of mosaic gravel habitats, especially on steeper embankments extending down to track level, will further diversify these habitats and reduce maintenance in potentially dangerous working environments. Equally, deploying the use of drones in the monitoring and inspection of landscape assets (for planting establishment inspections, fencing inspections, monitoring and identification of invasives species etc…), in dangerous or remote areas can offer cost and resource efficiencies, aid the early identification of issues, and de-risk maintenance activities by reducing operative exposure to potential risks.

Where appropriate, opportunities for management by livestock grazing to maintain the grass in appropriately located areas outside the security fence could be considered. This is a practice which has been undertaken in some areas on HS1, and depending on the adjacent land uses, has the potential to inform future land-use and ownership arrangements.

The distribution and nature of planting is influenced by the complex relationship between the many physical elements of the landscape combined with historical and cultural associations. Habitat-focused [11] planting design which builds on and connects into existing landscape and ecological wildlife corridors should look to create rich new ecological areas, ensure visually attractive and logical design solutions, and should aim to enhance the experience for rail users and communities along the entire route. In doing so, the designs should create specific features that add beauty to the landscape, avoid clutter, and collectively contribute to the HS2 ‘Green Corridor’ [8] (see figure 18).

Landscape Architecture as a discipline, and the role of landscape–led contextual integrated design thinking, can aid in the integration of all these elements, being uniquely placed to take a lead in coordinating multidisciplinary design to deliver successful functional and operational landscapes and maintenance regimes.

It is essential that all of HS2 is a well-designed and integrated infrastructure, forming one holistic design. This requires a joined-up and collaborative approach with close integration and engagement between multidisciplinary design teams, key contractor organisations, HS2, existing and future landowners, landscape managers, and open and creative conversations with local planning authorities and stakeholders. It is this integrated approach, along with an understanding of the complex interactions between people, place and time [1] that will unlock the full potential of HS2’s landscape and ecological legacy and the places it will create.

Case Studies

The below case studies, one HS2 Ph 1 example (the Colne Valley Western Slopes) and one built highway example (the A354 Weymouth Relief Road, Dorset), have been included to supplement this technical paper due to their exemplar design approaches to functional and operational designs which enhance biodiversity gains, and deliver sustainable contextual landscapes which will require lower levels of future management and maintenance.

Case Study 1

The cuttings of the A354 Weymouth Relief Road were established on subsoil, bare mineral or a thin scatter of topsoil and hand sown with native perennial wildflower seeds. The mix included Kidney Vetch, a pioneer wildflower that establishes prolifically on bare ground, leading to spectacular coverage within 18 months. The habitat has continued to diversify and now supports over 140 plants and 30 butterfly species, half the UK breeding species, demonstrating significant biodiversity gain above the improved agricultural fields the road replaced, and local landscape enhancement within the Dorset AONB.

No routine maintenance for safety or biodiversity has been required since the road opened in 2011, a situation likely to continue for several decades as the habitat matures. The whole–life carbon footprint of this approach is much reduced over a standard prescription involving topsoil and traditional maintenance regimes. This is a design approach which is very applicable to the HS2 landscape design earthworks treatments from both an ecological and functional perspective.

Case Study 2

The HS2 Western Slopes project in the Colne Valley demonstrates how a landscape–led design approach is being successfully achieved. Ninety hectares of calcareous grasslands which once thrived on the valley slopes are being recreated using chalk excavated from tunnelling in the Chilterns. The chalk will be sculpted to replicate the area’s dry valleys and deliver a range of microclimates. Concrete and limestone aggregate used in HS2’s construction will be recycled to add to the calcareous grassland to reduce the removal by truck to help minimise HS2’s carbon footprint. The proposals will deliver multi-functional habitats which provide wider project benefits and efficiencies including water management, soil protection, and the delivery of lower maintenance landscapes which maximise biodiversity and habitat value in a contextually appropriate manner.

References

[1] HS2 Design Vision.

[2] HS2 Landscape Design Approach.

[3] HS2 Phase 1 Environmental Statement documents.

[4] HS2 Sustainability Approach.

[5] HS2 information Paper E16: Maintenance of landscaped areas

[7] HSE: Managing health and safety in construction. Construction (Design and Management) Regulations 2015: Guidance on Regulations

[8] HS2 information Paper E11: Green infrastructure and the green corridor.

[9] HS2 Green Corridor Prospectus.

[10] HS2 information Paper D6: Inclusivity Design Policy.

[11] Joint Nature Conservation Committee – list of UK BAP priority habitats.

[12] Joint Nature Conservation Committee – list of UK priority species.

Peer review

- Ruth Lin Wong HolmesLondon Legacy Development Corporation