HS2 design approach to water integrated landscapes

Being of one of Europe’s largest infrastructure projects HS2 has the potential to redefine the way we shape our environment. The development of this scheme provides an opportunity for HS2 to positively influence the socio-economic and environmental challenges by offering a nature-based design approach that is integrated and landscape-led for a sustainable and resilient future.

The paper explores advantages of best practice and challenges during the design and implementation of HS2’s water-based landscape design in both rural and urban settings – integrating habitats for wildlife creation and mitigation, biodiversity, communities, user experience and heritage but also active travel in the form of new pedestrian and cycle networks. Through case studies, it demonstrates the established links between blue and green infrastructure networks.

Landscape architects are well-placed to play a significant role in leading the realisation of innovative and integrated water management in the UK’s urban and rural landscapes. This paper illustrates how they in collaboration with engineers and ecologists, can drive integrated water management through combined technical knowledge that form opportunities and key drivers for a nature-based solution.

This document lays out the HS2 integrated design approach followed when designing with water and its principles linked to blue and green infrastructure, landscapes, and complex infrastructure and how the objectives of the Design Vision helped deliver this integrated and joined up approach.

It is aimed at multidisciplinary design teams (including contractors and consultants) looking beyond the technical aspects with the aim to provide a clear and streamlined approach to water and nature-based design focussing on the integrated and multifunctional outcomes that the project and its users require and core to da design led approach supported by the HS2 Design Vision

Background and industry context

Since humans started to settle, flooding has always been a risk, but over the last decades due to climate change, it has become the most frequently occurring worldwide natural disaster and has resulted in the displacement of millions with thousands of lives claimed globally. Our ever-expanding urban centres and metropolis, coupled with a lack of permeable ground and deforestation, have resulted in changed occurrence of storm flooding at an unpredictable rate and damage which impacts more population in wider areas with greater cost to life and property than ever before [1].

As illustrated in figure 1, the recent floodings in the UK alone continue to have a negative impact on the housing values with insurances going up, loss of natural habitats and species extinction [2].

As a response to these socioeconomic and environmental damages occurring, adaption and mitigation strategies are being implemented in the world’s urban and rural areas and landscape architects play a key role in this. As the profession is directly linked to shaping the land, with the engineers and ecologists, we collaborate and apply techniques that not only respond to restoring nature but also creating environments where humans and other species can coexist in harmony.

The adaptation techniques which examined in this paper are the establishment of blue infrastructure in the shaping of landscapes.

A landscape-led approach is helping designers deliver towards the HS2 Strategic Goals and Objectives, the HS2 Design Vision [3], the Landscape Design Approach [4], and other design guidance, drawing on best practice and using examples from the HS2 projects.

It helps designers to achieve the ambitious level of design quality, integration, and sustainability that HS2 requires. It intends to ease the process by which designs are taken forward and can be accepted.

Blue infrastructure

Until a decade ago the default position for drainage was typically to feed water as quick as possible into the sewer network, watercourse, or the sea through a system of surface water gullies, culverts and channel drains. While this is an effective way to direct water away, in certain circumstances such as periods of extreme heavy rainfall, conventional water management systems can quickly become overwhelmed. In recent years as the negative effects of climate chance have become more apparent, effective water management through the use of green space is providing more natural and sustainable approach to drainage that enables water to be controlled closer to the source.

Water sensitive design developing rural landscapes, towns and cities around the water cycle has gained increasing traction over the past decades [5]. This sustainable water infrastructure is often referred to as blue Infrastructure involving rivers and canals, ponds and wetlands, floodplains and flood storage areas, storm water provision and drainage systems.

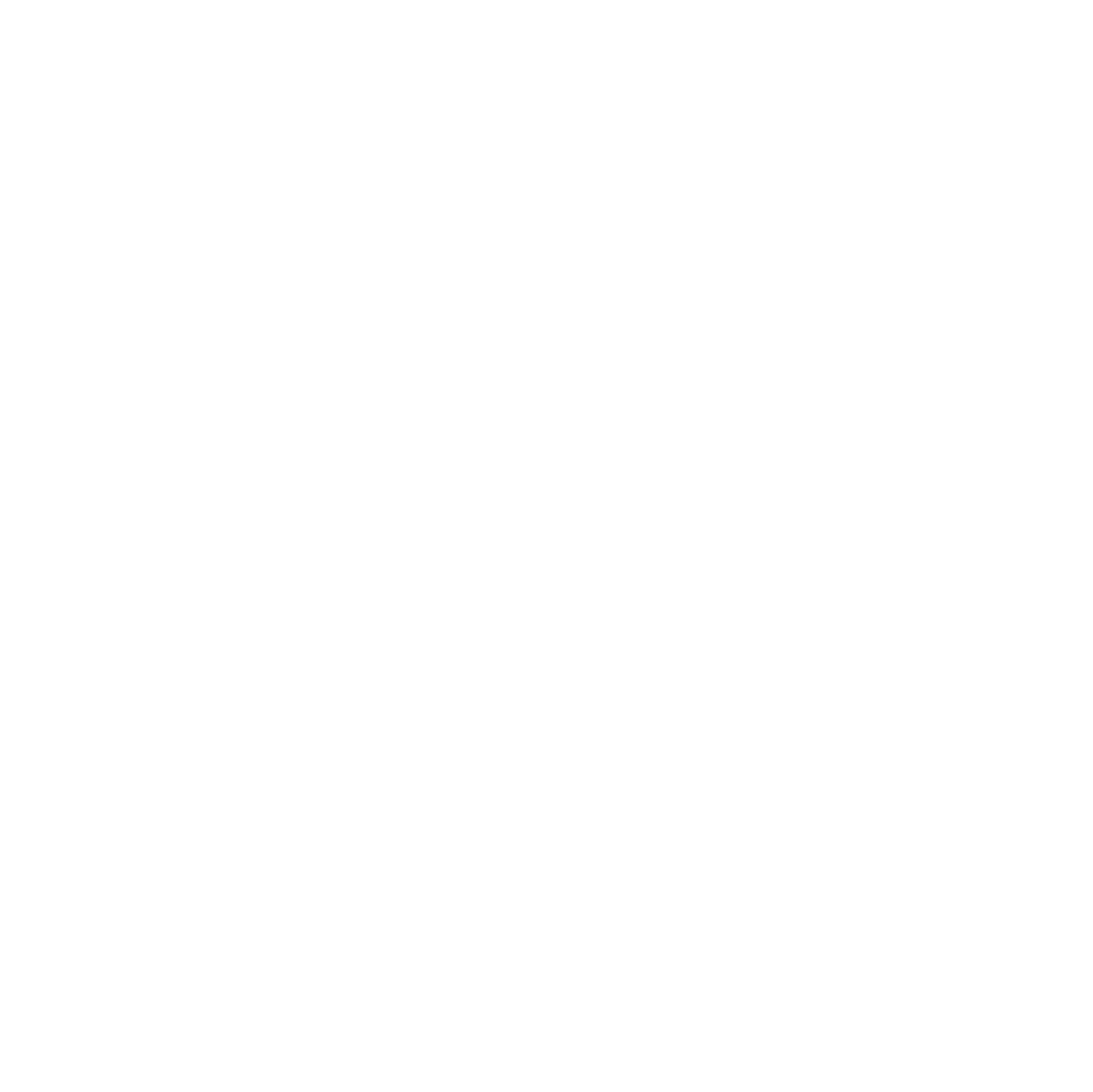

As shown in figure 2 below, blue infrastructure manages the risk of flooding whilst reintroducing a more natural water cycle into rural and urban environments and enabling adjacent areas to be incorporated and generate benefits for the environment, economy, and people.

Blue infrastructure is intrinsically linked to “green infrastructure” and is described by the European Commission – Water Framework Directive [6], as “A strategically planned network of natural and semi-natural areas with other environmental features, designed and managed to deliver a wide range of ecosystem services, while also enhancing biodiversity.” Such services include, for example, water purification, improving air quality, providing space for recreation, as well as helping with climate mitigation and adaptation. This network of green (land) and blue (water) spaces improves the quality of the environment, the condition and connectivity of natural areas, as well as improving citizens’ health and quality of life. Developing green infrastructure can also support a green economy and create job opportunities.’

A notable convergence of green with blue infrastructure occurs along watercourses where water naturally forms into a network of streams and rivers. This stability means that habitats develop adjacent, and the network can potentially support other regular patterns of activity by people and wildlife, providing for associated stable networks. Water remains a fundamental resource for wildlife and a route and means for species migration, it is attractive for activities such as observing wildlife and recreation. Because of the difficulties of arable farming and construction on periodically waterlogged land, the land adjacent to watercourses has often been left unimproved. Whether as countryside management projects, environmental land management schemes, integrated biodiversity delivery areas, nature improvement areas, or Heritage Fund landscape partnership projects, many environmental initiatives have been focused around a water network.

Severance is one of the big threats to the Blue Green infrastructure network integrity which is reflected on blue infrastructure in several ways, notably culverting and interruptions to the movement of people and wildlife. The fragmentation of ownership and varying approaches to fencing, land use and public access alongside rivers also compounds delivery of ecosystem that rely on continuity

The benefits of blue Infrastructure (figure 3):

- Blue Infrastructure provides effective and sustainable natural solutions to flooding and the protection of rural and urban communities with their critical infrastructure;

- Additionally, its features act as natural cleaners, reducing the number of contaminants and sediment in surface water runoff through settlement or biological breakdown of pollutants [7]; and

- Blue infrastructure enables the active use of rainwater and reuse of grey water for a dual water supply system that contributes to the protection of our increasingly stressed water resources.

Additional benefits of blue infrastructures include:

- Improving the amenity of an area, providing attractive, usable space for communities with a strong sense of identity and links to heritage;

- improving living environments: access to nature, recreation, education, improving air quality and microclimate;

- Providing and Improving habitats for wildlife and biodiversity; and

- Setting a context for regeneration and funding opportunities, jobs and skills.

At HS2 the benefits of a well-developed landscape-led blue infrastructure network are wide ranging and have a major beneficial impact on its cost, programme, operational benefits, and consents process [8],

Developing a blue infrastructure network is linked to HS2’s strategic goals as defined in the development agreement between the Department for Transport (DfT) and HS2 Ltd [9] with blue infrastructure design specifically relating to:

- Creating attractive places, through the integration of water, which generate future development and capital;

- Creating a unique experience for all users that contributes to a strong identity; and

- Providing a landscape solution that conserves, enhances, restores and transforms.

Design vision and aspirations

All design-related work is guided by the HS2 Design Vision [3] which sets out the role that design plays in making HS2 a catalyst for growth across Britain. The starting point is that HS2 will deliver value for money by applying the best in worldwide design and construction, but its mandate is to go beyond and be an exemplar project based on three core principles of people, place and time.

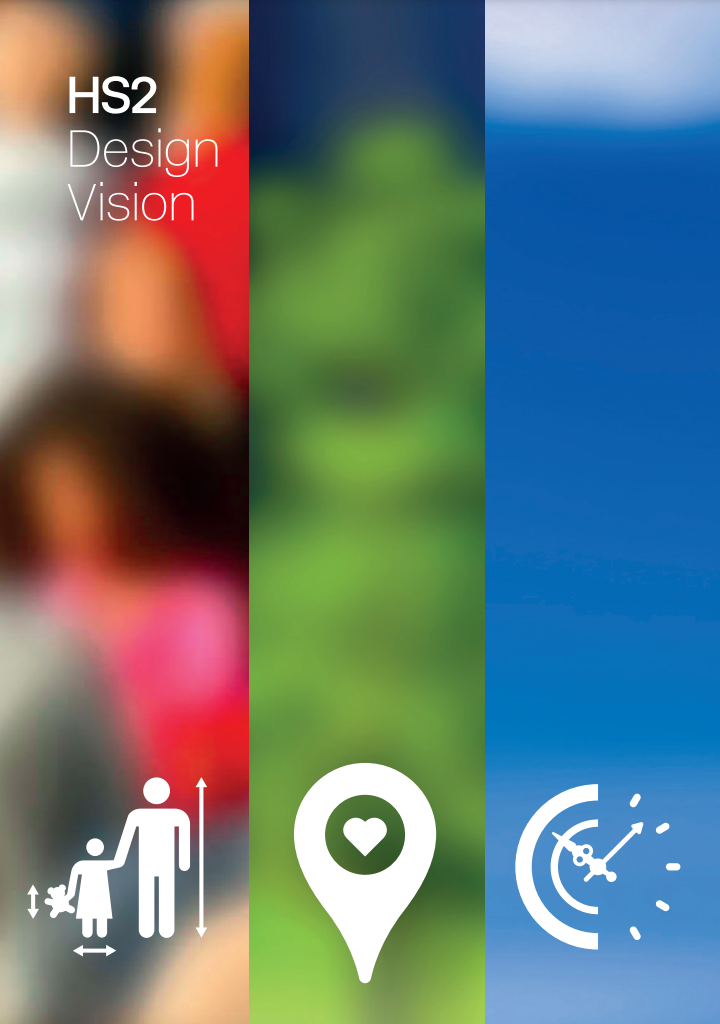

Based on principles set out within the HS2 Design Vision [3] the Landscape Design Approach [2] guides and directs the landscape design and outlines the approach along the route with the following points specifically relating to water – see figures 4 & 5:

- HS2 will require the provision of many new and diverted surface water features including balancing ponds, diverted rivers and streams, flood storage areas and water areas designed for ecological compensation;

- The approach will be to design these features to function well and contribute positively to the surrounding landscape through their alignment, shaping and bankside design;

- Surface water features will incorporate planting and wetland species for wildlife and habitat creation;

- Opportunities will also be taken to filter and clean water through natural means, through reed beds for example; and

- For buildings associated with HS2 rainwater harvesting and recycling will be considered.

Alongside the HS2 Design Vision stands the Green Corridor [10] as one of the key objectives of HS2 Ltd.’s Environmental Policy and is a term used by HS2 to describe the environmental mitigation, compensation and enhancement projects that will run alongside the railway; to create a network of bigger, better-connected, climate-resilient habitats and new green spaces for nature and people. It will be a home for wildlife while integrating the scheme into the landscape.

As the largest single environmental project in the UK, The Green Corridor’s main goals are to:

- minimise and compensate for the environmental impact of HS2 in rural areas, towns and cities; and

- supporting its neighbours to improve their local environment through several funding schemes supporting different projects.

Policies & strategies

As the climate changes and the population increases, blue/green infrastructure is fundamental to develop environments beyond HS2’s current requirements that are adaptable and resilient towards the future.

HS2’s position as one of the largest infrastructure projects in Europe gives it a unique opportunity to influence and shape a future of a landscape and ecology-led design approach with elements fundamental for the design and integration of major infrastructure projects.

The UK 25 Year Environment Plan sets out a comprehensive and long-term approach to protecting and enhancing the natural environment in England for the next generation [11] .It is a key policy driving HS2 to become one of the most sustainable railways in the world and its long-term contribution towards net zero and to achieve biodiversity net gain [12].

During all stages of its design, its construction and its operational stage, HS2 is required to demonstrate compliance with the legal requirements for the water environment in England and Wales as determined by the Water framework Directive [6].

The key objectives of the WFD are to:

- use river basin management plans and programmes of measures to protect and prevent deterioration;

- enhance or restore water bodies in order to reach good status;

- reduce pollution; and

- provide mitigation of floods and droughts.

Approach

Blue infrastructure provides an integrated approach centred around key principles summarised below and explored through the case studies in this paper.

A landscape led solution

When developing water integrated landscape solutions it is fundamental that a holistic and integrated systems-based approach is applied for a successful outcome through embedding natural systems integrated in the wider landscape context and resulting in multiple additional outcomes and benefits.

At HS2 this approach towards water management is addressed holistically across its vast landscape, environmental, engineering, but also economic and social dimensions to ensure that benefits are widespread and have a long-lasting impact.

Nature as a builder (combining functionality with nature-based solutions)

Blue infrastructure design should be led by nature-based thinking and the solutions it provides to manage and shape water environments. Specifically, this entails that the characteristics of the natural environment such as mimicking natural flows and patterns and implementing ‘soft engineering’ over hard.

The benefits of this overarching approach and as illustrated in figure 6, are wide ranging and include but are not limited to the re-alignment of watercourses, wetland restoration, floodplain meadows, natural flood management, wetland buffers and sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) that typically seek to slow the flow of water, regulate catchment flows, improve infiltration, increase water uptake, reduce pollution, and store storm runoff without discharging into combined sewer systems. It can increase climate resilience, reduce flooding, improve water quality, and prevent soil erosion.

Above all, and as set out in the HS2 Environmental Sustainable Vision [13], adaptability and flexibility are key for this system to be feasible and sustainable. In a world with fast environmental changes and requirements linked to government policies on climate change we need to ensure we build environments that are resilient and adaptable to future changes and can last infinitely.

A site-specific approach

In developing rural and urban landscapes Landscape Architects incorporate water management solutions, topography, and ecology to create systems that divert, absorb, or capture water whilst creating environments that are sympathetic to their wider rural and urban contexts.

This is particularly crucial for large infrastructure projects like HS2 where the core design work, within the project limits needs to be carefully understood and linked to the wider environment. In particular, the water catchment and landscape character areas need to be considered to achieve blue infrastructure designs that are holistic, integrated and deliver the wider outcomes for HS2, its users and stakeholders.

Additionally, At HS2 the environmental impact and subsequent required mitigation are carefully incorporated in the design proposals responding to all environmental and engineering issues.

Multifunctional results for biodiversity & people

A landscape-driven water management design at HS2 delivers beyond project boundaries and constantly pushes the envelope to a multi-layered and revitalising outcome for people and places throughout time. It provides additional opportunities relating to the creation or the enhancement of habitats and ecosystems that in turn contribute to HS2’s Green Corridor and biodiversity no net loss / net gain [10].

The HS Ecology document states: “In addition to improving water quality and the creation, enhancement and preservation of natural and biodiverse habitats an interdisciplinary approach between Landscape Architects, engineers and ecologists is key to provide a landscape system that incorporates heritage, public realm, cycle and pedestrian networks and other leisure and recreational opportunities where possible” [14].

It is the role of the Landscape Architect to bring these respective elements together through a landscape-led approach to establish well-integrated, beautiful, sustainable, and recognisable places in line with the National Planning Policy Framework [15] and the HS2 Landscape Design Approach [4] that further contribute to people’s wellbeing, pride and HS2’s landscape legacy.

Components

Throughout its journey, HS2 constantly interacts with water that varies in nature and function depending on location and requirements of the 225 km long rail line.

Whether watercourses, balancing ponds and wetlands, floodplains, or drainage systems in both rural and urban settings, they all require an integrated approach that incorporates the Blue Infrastructure principles set out above.

Watercourses

Along its route, HS2 crosses more than five hundred bridging structures, including over fifty major viaducts (measuring a total length of 15km), bridges and culverts which will stretch across valleys, rivers and canals. As a result of this it is inevitable that some watercourses require realignments such as the River Cole illustrated in figure 7 or diversions to accommodate or offset the effects of the HS2 infrastructure.

Due to its sheer scale and complexity HS2 is in a unique position to establish watercourse and habitat improvements on a national scale, setting important standards and precedents that are aligned with the WFD objectives and HS2’s Technical Standard for Watercourse Diversions and Realignments but also adding to the ‘no net loss’ and HS2’s Green Corridor goals.

Watercourses mainly interact with HS2’s network through culverts, viaducts and bridges which is where specific interventions and measures are considered [6]:

- To primarily keep watercourses uncovered and as natural as possible for the benefit of ecology and communities by prioritising clear span viaducts and bridges over culverts;

- To incorporate the watercourse hydrology and dynamics to respond to the unique site characteristics and wider context and to ensure its habitats are adaptable to change;

- To enable, through close collaboration with hydrological engineers and ecologists, a watercourse that is natural looking and incorporates typologies that reflect this such as riffles, pools, scrapes, channels, and marginal vegetation;

- To explore (across HS2’s vast works on a regional scale) opportunities to (re)naturalise and improve existing watercourses as part of the realignments and diversions to reinstate stream dynamics and associated riparian habitat;

- To seek opportunities for reconnecting severed floodplain areas along watercourses to increase flood water capacity, reduce flooding and enhance ecological connectivity;

- Where culverts are used it is important that optimum habitat connectivity for wildlife movement is provided through specific features such as badger ledges and natural direct or passive lighting; and

- As part of HS2’s commitment to design well-balanced places for people and environment, integration of leisure and recreational areas should be provided where possible throughout the watercourse landscapes and between communities.

Case study: The River Cole

The River Cole is located within the West Midlands, where the HS2 route sweeps west towards Birmingham and branches north, forming a unique triangle of infrastructure. As illustrated in figure 8, this includes two viaducts, landscape embankments and the consequent realignment of the river Cole to enable these to be physically achieved. The area has a rich history, including a medieval deer park, the Tudor Coleshill Manor and the Elizabethan Garden which was uncovered by HS2 archaeologists.

The redesign of the river required a multi-disciplinary approach to achieve a design compliant to all constraints through an interdisciplinary and landscape-led approach aimed at recreating and improving riparian habitats and biodiversity integrated into the wider landscape and its heritage.

The realignment is designed to simulate the existing flow capacity, maintaining adequate radius to avoid erosion at meanders and to keep the length no shorter than the existing channel. Flooding was assessed to ensure the diversion does not exacerbate risk for the 120-year lifetime of the project. Adjoining the realignment, replacement floodplain storage areas have been incorporated. These drainage features have been realised as opportunities for additional planting, providing ecological habitat and contributing to the project’s biodiversity.

Habitat connectivity in the realigned river is a key objective. This is aimed to be achieved through swathes of wet grassland and riparian planting along its’ banks, creating ecological habitats and a small ecological park under the river Cole viaducts. Hydraulic considerations are of utmost importance due to the area’s location within the river Cole flood zone. Planting palettes have been developed in close collaboration with the river engineers to ensure compliance with hydraulic constraints. Where flow velocity decreases, opportunities for increased planting emerged. The riverbanks have been categorized into distinct planting types to be adapted to local characteristics.

The introduction of HS2 infrastructure has provided a unique opportunity to establish a new relation between the railway, the landscape and the local communities by enhancing the historical significance of the area and its ecological features as shown in figure 9. Consequently, the landscape project aims at transforming the scheme from an infrastructure project into a catalyst for the creation of a holistic design project emphasising the local richness.

Balancing ponds:

Balancing ponds (figure 10) form an integral part of HS2’s make-up as they directly receive water run-off from the new railway track areas and prevent these from flooding during rain events. The ponds enable the collection and gradual release of the collected water to prevent an increase in flooding from the new surface water drainage areas. Generally, and at HS2 three types of balancing ponds [16] are in use:

- Attenuation ponds, which can temporarily store fast water runoff and then gradually discharge it at an agreed lower rate (and taking into account climate change allowances) to a nearby watercourse, resulting in the reduced risk of localised flooding;

- Infiltration ponds, which allow water run-off to be absorbed into the ground where conditions allow (a preferred option for sustainable drainage); and

- Hybrid ponds, which combine the features of both attenuation and infiltration ponds.

Although their primary function is linked to flood management, the sensitive integration of the HS2 balancing ponds as natural wetland features is of fundamental importance. The ponds provide replacement of lost habitats (because of HS2 works), contribute to ecological connectivity, no net loss, improving water quality but also the crucial provision of visual amenity.

When forming and integrating the balancing ponds at HS2, a variety of operations is applied to achieve an optimal and well-balanced outcome and include [6]:

- The linking to and mimicking of the existing surrounding natural topography resulting in natural-looking ponds with varying profiles and slopes (S-shaped slopes), dry and wet benching to enable plant growth and development of a variety of habitats and organisms within and along the pond edges;

- The sensitive integration to avoid loss of existing trees and habitats and to ensure appropriate offsets to trees to avoid leaf fall that can subsequently lead to failure of the hydraulic structures;

- The seamless incorporation of maintenance access areas and security measures, following in-depth risk assessments, to obtain a visibly unobstructed and optimum outcome;

- Where possible security fencing should be removed through departures and replaced with boundary fencing, hedgerows, or topographic interventions; and

- Where possible, opportunities for leisure and recreation should be explored in the form of swimming, playing, resting, and observing.

Floodplains and flood risk management:

Floodplains are important in naturally reducing flood water volumes and rates. New level changes in a floodplain area can negatively impact the available storage capacities and subsequently increase flood risk downstream. It is HS2’s goal to ensure that flood risks are not increased during the lifetime of the development, including an additional allowance for climate change. Where possible, the design of the scheme has sought to avoid floodplain areas, and where not the loss of storage has been compensated for by creating replacement flood storage areas.

Replacement flood storage (RFS) areas are provided to mitigate the impact of the proposed scheme on existing floodplains and to ensure that the Proposed Scheme does not cause risk to vulnerable receptors (e.g. residential property) because of its construction or operation [13].

A Nature-based approach alongside or instead of engineered solutions using natural processes are fundamental at HS2 to provide flood storage areas that are sustainable and visually integrated and add benefits such as habitat creation and the reduction of maintenance costs.

To successfully develop replace flood storage areas, HS2 has set out key principles [6] that are applied throughout the landscape-led design process and have been developed in close collaboration with engineering and ecology disciplines:

- To first and foremost limit the impact on floodplains by adding viaducts, shortening embankments and reducing impermeable surfaces;

- Link to the surrounding topography to achieve a seamless integration and plan for won soils to be reused on site or in close vicinity;

- Keep the removal of existing vegetation to a minimum to limit ecological mitigation and encourage tree planting within the replacement flood storage areas to improve landscape integration linked to HS2 infrastructure;

- Incorporate flexibility for future multifunctional use such as grazing pasture or ecological or amenity uses when not required for agriculture; and

- Integrate public access including leisure and amenity areas abiding to health and safety requirements.

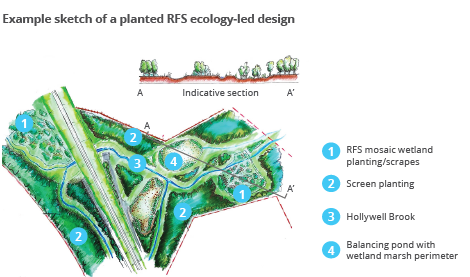

Case study: Hollywell Brook

The proposed landscape and public realm at the new HS2 Interchange Station echoes and is drawn from the surrounding Arden landscape. A set of guidelines was developed around the Arden landscape [17]. It is characterised by a ‘wide range of historical and ecological features, that create a landscape of intimacy with a strong sense of place. Most significantly it remains a wooded landscape with mature hedgerow oaks, ancient woodlands and historic parklands’.

The area south of the station is shaped by the realigned Hollywell Brook which will form the backbone of a new park landscape centrally located in a sustainable new business, leisure and residential destination and world leading economic hub.

During the design process, HS2 has carefully considered how it can minimise impact on the natural environment, and the protected wildlife species by exploring an ecologically led design within the replacement flood storage areas alongside Hollywell Brook that form the framework for this new mixed-use development.

As illustrated in figure 11, the proposed RFS areas will be composed of a mosaic of wetland planting and scrapes where the water will flow through clusters of different habitats and plants, which will successionally vary from marshland species near the river, to mixed species grassland and planting integrated with the surrounding areas, and finally to woodland towards the edges of flood storage areas.

Flood water is proposed to be an integral part of the scheme that will help shape the general arrangement of this new living and working neighbourhood whilst providing a dynamic and seasonal changing relationship with the water environment.

Sustainable drainage systems (rural and urban conditions)

Drainage requirements occur over the entire route with numerous surface water run-off and other discharges to watercourses, canals, highway drainage systems resulting from HS2’s large and complex infrastructural interventions.

The solutions sensitively integrate into the surrounding landscape and in accordance with the Landscape Design Approach. However it is the more build-up and urban areas with depots and stations that present the biggest challenges where large operational areas complicate water and drainage systems.

It is of fundamental importance that when developing these challenging landscapes, the whole water cycle management including rainwater harvesting and the re-use of water which can reduce the total water and energy footprint are considered.

Sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) [18] are designed to manage stormwater to mimic natural drainage, encourage infiltration and attenuation and provide natural treatment through soft engineering. Its composite buildup enables mitigation against the impact new development (buildings and infrastructure) has on erosion, surface water flooding, sewer capacity, water quality and natural habitats .

Additional benefits of SuDS are:

- Improving amenity and biodiversity: the integration of green infrastructure with SuDS solutions help to shaping habitats and recreational and biodiversity areas;

- Water resources: SuDS help to recharge groundwater supplies and capture rainwater for re-use;

- Community benefits: well-designed public open space that incorporate SuDS help to creating better communities through and quality improvements;

- Recreation: multi-purpose SuDS components can act as sports/play areas;

- Education: SuDS in schools provide a fantastic learning opportunity that provide additional recreational space; and

- Enabling development: SuDS help to increase capacity in already established drainage networks.

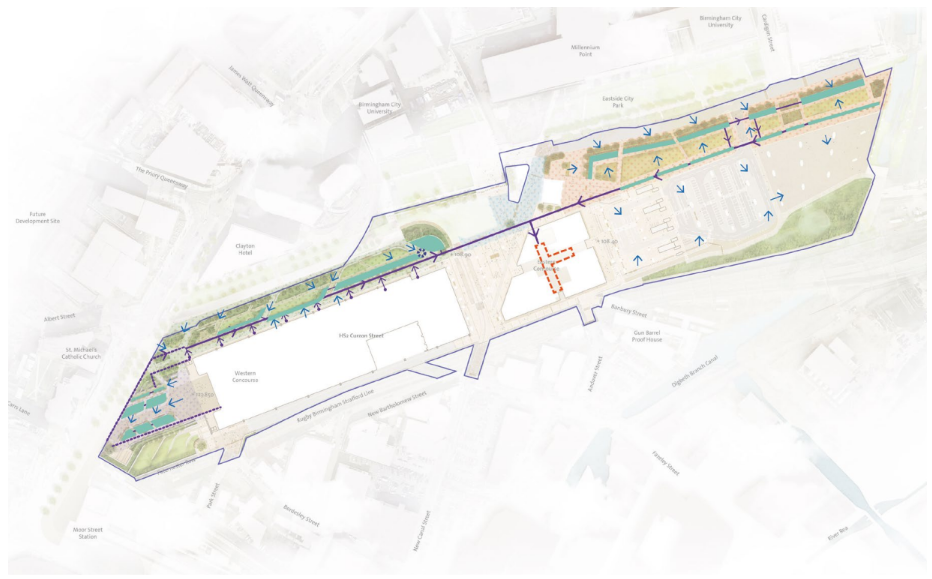

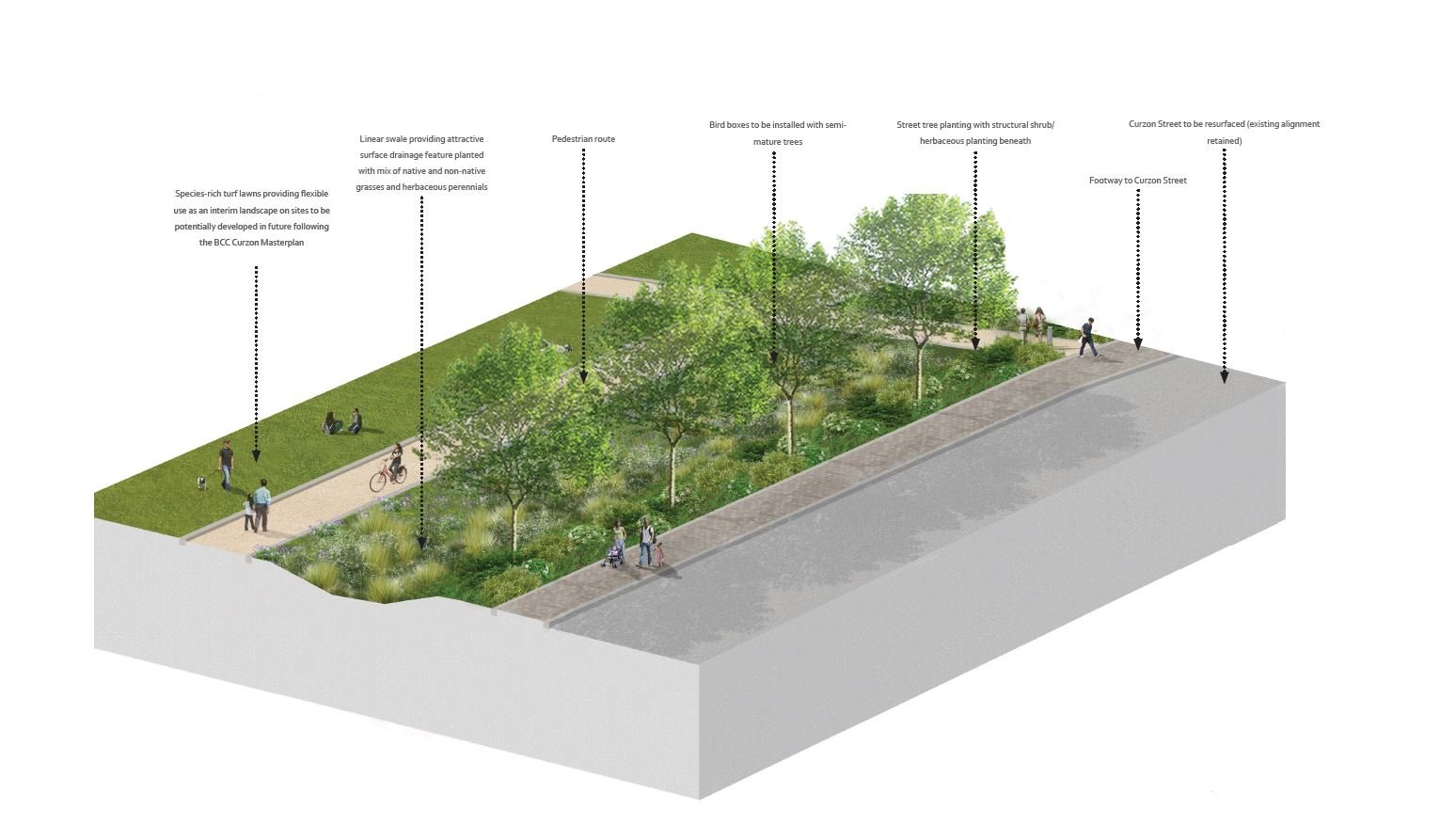

Case study: Curzon Street public realm

At Curzon Street (figure 12) a sustainable drainage-driven approach to surface water management has shaped the framework for the development of the public realm.

Compromising a fully integrated, water sensitive design where the station’s and wider topography, soft and hard landscape function in tandem to create rain gardens that slow the surface water run-off, contribute to the reduction of urban heath, lower maintenance requirements and ultimately contribute to a site-wide sustainable design [4] as illustrated in figure 13 and 14.

Spatial restrictions and complex utility requirements led to the application of rain gardens that can retain large volumes of water in relative compact areas that in turn free up significant valuable land for future development. The multifunctional nature of the gardens enables the integration of recreational and leisure areas creating a high quality hard and soft landscape that instil a unique sense of arrival and departure, facilitating movement through attractive places to meet and greet.

Outcomes

This paper explains and unpacks HS2’s design approach to Landscape design with water in which it sets outs strategies to successfully incorporate and combine hydrology, drainage, ecology and heritage with landscape as its binder across vast and diverse habitats. The enormous scale of HS2 creates a unique opportunity to tackle challenges and prescribe solutions in an unprecedented way. It demonstrates:

- the meaning of blue Infrastructure, why it is important for environment and people and how HS2 implements it throughout its vast landscapes that interface with complex infrastructure requirements related to the high-speed network.

- Linking and alignment to various national and international policies and the HS2 Technical Standards and guidance documents such as the Water framework Directive, HS2 Green Corridor Prospectus, and Information Paper E21: Balancing Ponds and Replacement Flood Storage Areas.

- the paper highlights the challenges related to blue infrastructure notably culverting and interruptions caused by structures and its adverse effects on biodiversity, ecosystems, connectivity, and community.

- The involvement of Landscape Architects in the development of green and blue infrastructure drives changes in the way that land is used to promote blue/green networks, prevents their severance and is adaptable and resilient towards the future.

- Design strategies: the paper explains how HS2 approaches the challenges related to blue infrastructure and how integrated landscape solutions are fundamental for a holistic and integrated systems-based approach. The case studies demonstrate successful embedding of natural systems integrated in the wider landscape .

- HS2’s blue Infrastructure design approach establishes a holistic and fully integrated landscape design. The key principles are to (1) use nature as a builder, (2) apply a site -specific approach and (3) provide added benefits related to biodiversity, people, and place.

Learning and recommendations

This Learning Legacy Paper demonstrates HS2’s approach when designing with water through all stages of the project. It highlights its principles and strategies, the integration with surrounding blue and green infrastructure and the various infrastructure elements it incorporates.

The key recommendations from this paper are as follows:

- A landscape-led and nature-based approach is fundamental to achieve an ambitious outcome to provide a high design quality, integration, and sustainability on major projects.

- Understand and work towards a wider context, in particular the water catchment and landscape character, to achieve blue infrastructure designs that are holistic, integrated and aspire wider outcomes.

- Blue Infrastructure provides effective and sustainable natural solutions to flooding and the protection of rural and urban communities with their critical infrastructure

- The integration of Blue and Green infrastructure is key to shaping better integrated and connected habitats with increased biodiversity.

- Incorporate the watercourse Hydrology and dynamics to respond to the unique site characteristics and wider context and to ensure its habitats are adaptable to change.

- Seek and embrace opportunities for reconnecting severed floodplain areas along watercourses to increase flood water capacity, reduce flooding and enhance ecological connectivity.

- Enable the development of well-balanced places for people and environment, integration of leisure and recreational areas to be provided where possible throughout the watercourse landscapes and between communities.

- Providing a landscape solution that conserves, enhances, restores, transforms and encourages opportunities beyond required limits, including environmental and community legacies.

Conclusion

HS2’s approach to blue infrastructure is a testament to its vision and dedication to contribute to wider outcomes and a positive environmental and community legacy. The various strategies and technical standards related to water, and Green Corridor demonstrate this.

HS2 constantly interacts with water systems in many ways and conditions. The well-developed design approach and strategies contribute to wider outcomes beyond project boundaries and a positive environmental and community legacy for HS2.

As one of the largest infrastructure projects in Europe, HS2 is helping to redefine the way we shape infrastructure and integrate it with our environment and natural world.

At HS2 blue Infrastructure presents valuable and creative opportunities to enhance developments for people and the environment. Landscape architects play a pivotal role in maximising the benefits of water environments through best practice and early integration in the design process including: placemaking driven from an ecological and hydrological perspective and adding social value.

Severance is one of the big threats to the integrity of blue infrastructure with structures like culverts and viaducts limiting movement of people and wildlife. The HS2 blue infrastructure proposals address this by providing specific solutions to mitigate the issues related to fragmentation and enhance biodiversity, and ecological and community connectivity.

Whether in rural or urban conditions, a landscape led approach adds specific value to the design by taking a holistic and multidisciplinary approach. An early involvement is fundamental to ensure the integration of water and drainage aligns with and enhances the projects broader vision, benefiting the place, users, and environment through a blue-green infrastructure approach to landscape design.

HS2’s blue infrastructure approach and strategies are demonstrated in the various project examples such as the River Cole realignment, the Hollywell Brook replacement flood storage landscape, or the extensive rain gardens at Curzon Street Station where the sustainable drainage strategy has driven the placemaking of the urban realm.

With an emphasis on offering a nature-based design approach that is integrated and landscape-led, HS2 sets precedents and new industry standards for responsible development that values the intrinsic connection between people. place and time for a sustainable and resilient future.

References

[1] UNHCR The UN Refugee Agency Climate change and displacement

[2] Friends of the Earth Policy Is flooding in England getting worse

[3] High Speed Two Limited (HS2 Ltd.) HS2 Design Vision.

[4]High Speed Two Limited (HS2 Ltd.) HS2 Landscape Design Approach.

[5] The Landscape Institute Technical Information Note – Water, Flooding & Landscape

[6] The Water Environment (Water Framework Directive) (England and Wales) Regulations 2017

[7] The Flood Hub. How Blue-Green Infrastructure Can Reduce Flood Risk and Provide Lots of Other Benefits

[8] High Speed Two Limited (HS2 Ltd.) HS2 Blue Infrastructure Design Approach

[9]High Speed Two Limited (HS2 Ltd.) HS2 Development Agreement

[10] High Speed Two Limited (HS2 Ltd.)Green Corridor Prospectus.

[11] Gov.UK A Green Future 25 Year Environment Plan

[12]High Speed Two Limited (HS2 Ltd.) HS2 Net Zero Carbon Plan

[13]High Speed Two Limited (HS2 Ltd.) HS2 Environmental Sustainable Vision

[14]High Speed Two Limited (HS2 Ltd.) HS2 Ecology

[15]Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government The Government’s National Planning Policy Framework

[16]High Speed Two Limited (HS2 Ltd.) HS2 Phase One Information Paper E21: Balancing Ponds and Replacement Flood Storage Areas

[17] Solihull Metropolitian Borough Council Warwickshire Landscapes Guidelines Arden Landscape

[18] Susdrain

Peer review

- Kay Hughes HS2 Ltd

- Susie Woodward-MoorHS2 Ltd