Implementing remote site inspections

During the first Covid-19 lockdown starting in March 2020, construction on High Speed Two (HS2) continued. In order to enable safe working practices on site, social distancing and protection of the clinically vulnerable, NEC supervisors utilised video conferencing with contractors to remotely conduct inspections and witness testing as per their duties under the NEC3 contract. Video inspections have included factory assurance tests, pre-completion checklist site walkthroughs, as well as utility and drainage construction and testing. Looking into the future, remote inspections may be a way to conduct multiple inspections across a wide geographical area in a single day as well as expand into real-time drone inspections for hard-to-reach areas, confined spaces, and to inspect sites, particularly environmental aspects such as plantings and stockpile inspections. This paper details how video inspections were implemented on HS2 and how it could be useful for other projects to consider.

Background and industry content

On 23 March 2020, the UK went into what turned into the first Covid 19-related lockdown, with the temporary closure of schools, shops and offices across the country. In order to ‘flatten the curve’, much of the country started working from home unless they were essential workers. On the 30th March, the first orders went out to the clinically extremely vulnerable – where both the elderly and members of the workforce with certain health conditions were requested to shield by staying at home. The very next day, the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, wrote a letter to the entire UK construction sector, outlining how the industry was instrumental to the British economy. To those working within the industry and High Speed Two (HS2) in particular, it was apparent that if works were to continue to progress and keep to any sort of programme, the very essence of how works were undertaken would have to change in order to keep workers safe and to prevent further transmission of the virus. This included how the works were assured by those within HS2, including NEC supervisors.

The supervisor is one of the four named roles within the NEC3 (3rd New Engineering Contract), the legal contract on which HS2 and most major infrastructure projects are tendered, awarded and administered. The role of the NEC supervisor is an independent one. Where the project manager and contractor may be more concerned with cost and programme, the supervisor works on behalf of the employer as the arbiter of construction quality. Their job is to ensure that what is built and the quality of what is built matches what was contracted under the NEC3’s Works Information. This includes ensuring the correct materials are used and that the works are built to the correct design, specification and standards. NEC supervisors undertake this by monitoring progress, observing tests, reviewing assurance documentation and when things go wrong, raising defects. In non-Covid times, the supervisor is a regular presence on site.

Once the pandemic took hold, it became obvious that “business as usual” could not continue on site. Contractors across the HS2 route adapted their working processes to ensure that operatives were two metres apart when possible, and when not possible, that the correct PPE was worn. Various methods of ensuring social distancing were used – from adopting one-way systems in offices to adapting plant proximity sensors to be worn by site operatives, beeping and buzzing when they were not appropriately distanced on site. In addition to innovating how site operatives and engineers worked, reviews were undertaken to check exactly who needed to be on site – and when. These reviews took into question much of the following: how many operatives were needed to safely undertake the works? How many engineers, surveyors, and other site-based staff were needed to assist, measure, test, supervise, assure and analyse the works being undertaken? Could some usual site staff be moved offsite or at least further away? Could they obtain their data by other means? Could some roles be done remotely – particularly if that role was undertaken by someone who was also shielding?

The HS2 supervisor team is a small team undertaking supervisor duties for the entire early works contracts, main works civils contracts and station contracts from Euston to just north of Birmingham. The team is split into contracts geographically and are assisted by route-wide supervisor specialists in utilities and environment. During the periods of lockdown, many supervisors had to limit their site activities due to personal circumstances, site constraints and in order to not become vectors for Covid themselves by carrying it from one site to another in the course of their duties. During this time, remote and virtual inspections were developed and undertaken between contractors and supervisors in order to fulfil the assurance obligations and responsibilities under the contract.

Of the many inspections and tests that were undertaken during the course of the pandemic lockdowns to date, five have been singled out for this learning legacy review: a COWL site walkthrough inspection, an air test for sewer, a sheath test and pressure testing on high voltage cables, mandrel testing of communications ducting, and a factory assurance test of switchgear.

COWL site inspection

A COWL (combined outstanding works list) is a list required by the NEC3 contract which lays out all outstanding works, including site works, surveys, as-builts, tests and documentation required to complete a package of works. It is drawn up by both the contractor and the supervisor and is progressively reviewed as completion nears. Any works outstanding at the time of contractual completion become defects.

This site inspection was undertaken on a large site north of Birmingham, the scope of which consisted of the construction of a haul road, drainage, utilities, an attenuation pond and other works that enabled the start of main works. Prior to the inspection, the contractor and supervisor held a meeting to set up the remote inspection. As a part of this, they reviewed the COWL and agreed which items would be inspected via these means. Additionally, the Contractor and NEC supervisor agreed what photographs would be needed to verify that the works had been undertaken to a good standard, including providing context for location. It was agreed to use Teams to start the call, using WhatsApp as a backup. The Contractor set up the COWL in a geographic manner, so that all site-based outstanding works items could be reviewed in a logical manner.

During the inspection itself, COWL items were able to be clearly seen and closed as outstanding works. Dead testing of the electrical components, lighted pedestrian bollards, was undertaken at the same time. The video was to a good standard, as long as the Contractor panned slowly or held the camera still to enable the NEC supervisor to review the item being inspected. This requirement for holding still and slow pans was a result of weak 4G signals in more rural locations. As the inspection continued, the NEC supervisor was able to request photos for assurance purposes and take screenshots as necessary. Unfortunately, the contractor was unable to hear the NEC supervisor for much of the call due to wind, requiring the NEC supervisor to message the contractor further comments and requests. This made the call last longer than necessary. In addition, the contractor’s phone lost battery halfway through the inspection, so a backup device had to be used to finish the call. In all, about 15 items, from piling mats to dead testing to small snags in drainage to reviewing ditch repairs were remotely inspected.

As a result of this inspection, the contractor started wearing headphones which allowed for somewhat better communication during remote site inspections. Additionally, this was the basis for further remote inspections and laid the groundwork for them going forward. Ensuring that the works and remote inspection were discussed ahead of time, agreeing inspection points, good communication and a good working relationship between the parties were key positive lessons that were taken forward to further remote inspections. Noting the limitations to the technology, including the battery life of devices, microphones / speakers defeated by weather, and lower signal in more rural areas was also taken into account in the planning of subsequent inspections.

Sewer air test

One of the main utility undertakings for the enabling works has been the diversion of existing sewers away from the path of the track route from Euston to Birmingham. Additionally, new sewers are being constructed to manage the surface water runoff and sewage near the worksites and future route. A standard test performed when a new sewer is constructed is an air test, which tests the airtightness (and thus watertightness) of the pipe.

In order to witness the air test of a new sewer near North Acton, the contractor and NEC supervisor held a quick meeting to discuss how the test could be performed and remotely inspected in a safe manner. Unlike the COWL site inspection above, this test was undertaken on an active construction site, in a trench and adjacent to live traffic. The contractor health and safety team was contacted in order to assess the safety of the remote inspection whilst in these conditions. It was allowed, but all plant movement and adjacent works were to be stopped while the test was being undertaken. This allowed the contractor engineer who was monitoring the test and assisting in the remote inspection to concentrate on both the test and the remote inspection. Additionally, due to the shallow nature of the sewer, the engineer was able to stay at the surface while monitoring the air pressure on the manometer.

During the air test remote inspection, the contractor demonstrated the bund placement within the sewer; this was shown as the test began. Due to the sunny day, it was often difficult to capture the loss of pressure over the five minutes on the manometer, so the NEC supervisor kept having to ask the contractor engineer to tilt the iPad. In addition to the air test, the NEC supervisor was able to observe the trench, the bedding of the pipe, the pipe installation, and the surround to the pipe. A further test was undertaken between chambers following backfill and reinstatement of the roadway, which was observed at a later date.

This rather simple test, which lasts approximately 5 minutes once the pipe is up to the requisite pressure, was easily captured via remote video inspection, with good communication between the contractor and Engineer. It was agreed by the contractor and NEC supervisor that this test and other routine tests like it was an ideal candidate for ongoing remote witness inspections. Going forward, during the planning phase, a safe system of work while undertaking the remote inspection was discussed. Additionally, it was noted that the light and mobile internet signal made the manometer somewhat difficult to read, which is already difficult under normal circumstances due to the gauge being a clear liquid in a clear tube.

Mandrel testing

One of the other main undertakings for the enabling works utilities teams was the installation of ducting for electrical, telecommunications and fibre networks. After the ducts have been installed and roadways and pavements have been reinstated, the final test for the ducts is proving the ducts with a mandrel. At Euston, the ducts were so numerous it was joked that the number of ducts exceeds the number of noodles in the average bowl of spaghetti bolognaise. These ducts were placed to allow for diversions around the new Euston station footprint and away from the path of the new tracks coming out of Euston.

Ahead of testing, the contractor engineer spoke with the NEC supervisor, discussing what would likely be able to be shown and what would not be due to site constraints. The contractor also sent over a sketch noting each set of ducts that were being tested. The contractor already underwent the site safety risk analysis with their health and safety team, and as there were no active works in the area, the remote inspection could go forward. The call was going to be captured and recorded on Teams, with both the NEC supervisor and asset owner’s assurance engineer in attendance. Due to site constraints, the Teams call was preferred to allow social distancing.

On the day of testing, the contractor engineer had a 4G-enabled iPad in use, and using Teams, performed the remote inspection. The site operatives easily demonstrated the mandrel on the far end of the testing area, and easily pulled the mandrel through each duct. Despite the contractor’s concerns that a test being performed over a distance would be difficult to capture remotely, the mandrel test was an easy test to view, as was literally watching a mandrel pulled by rope and coming out the other end of a duct. The contractor engineer was able to give context as to which ducts were being tested by panning around to local buildings and street signs, as well as demonstrating the good practice of stopping the ducts after testing to keep debris out of the ducts.

Factory acceptance test

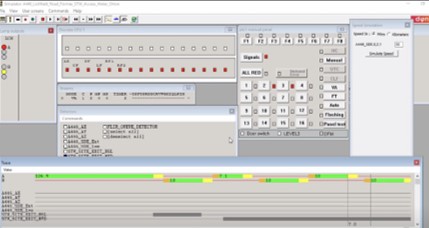

Several factory acceptance tests of traffic signals, electrical switchgear and electrical transformers were undertaken during lockdown. The development of how these factory acceptance tests were undertaken and presented remotely by the manufacturers over the course of the pandemic is astounding.

At the start of the pandemic, the NEC supervisors attended a remote inspection where switchgear was assurance tested prior to site delivery. The assurance tests were live performed using a fixed camera using Teams, with the factory engineers performing the tests explaining what they were doing for each round. This was not always easily visible – which is something that can also be an issue for factory acceptance tests in person. The test protocols were not sent out ahead of time, so it was difficult to track progress of the testing and what the expected outcomes were to be for each test undertaken. Additionally, the test was not video recorded, with the results recorded solely on checksheets.

In a further factory acceptance test undertaken in January 2021, the engineers had a wifi-enabled Go-Pro style camera attached to their body and additionally wore a headset. These items allowed for easy remote viewing of the tests being undertaken while allowing the Engineer to concentrate on the tests he needed to perform. Additionally, the factory team sent over the testing protocol days before the assurance tests and had a question-and-answer session before the tests were undertaken. The assurance tests were done via Teams and recorded in Teams for review purposes.

Factory acceptance tests often occur around the world and all over the United Kingdom, from Barrow-Upon-Furness for electrical switch gear to Germany for the construction of the TBM and Malaysia for transformers. The evolution of the remote factory acceptance test from a stationary camera to agile hands-free cameras and headsets that allow participants viewing the tests to have an engineer’s view of the testing setup and results demonstrates that factory acceptance testing may have a permanent future in remote inspections. This would remove the need for NEC supervisors and other assurance engineers to travel for these tests.

Sheath and pressure testing

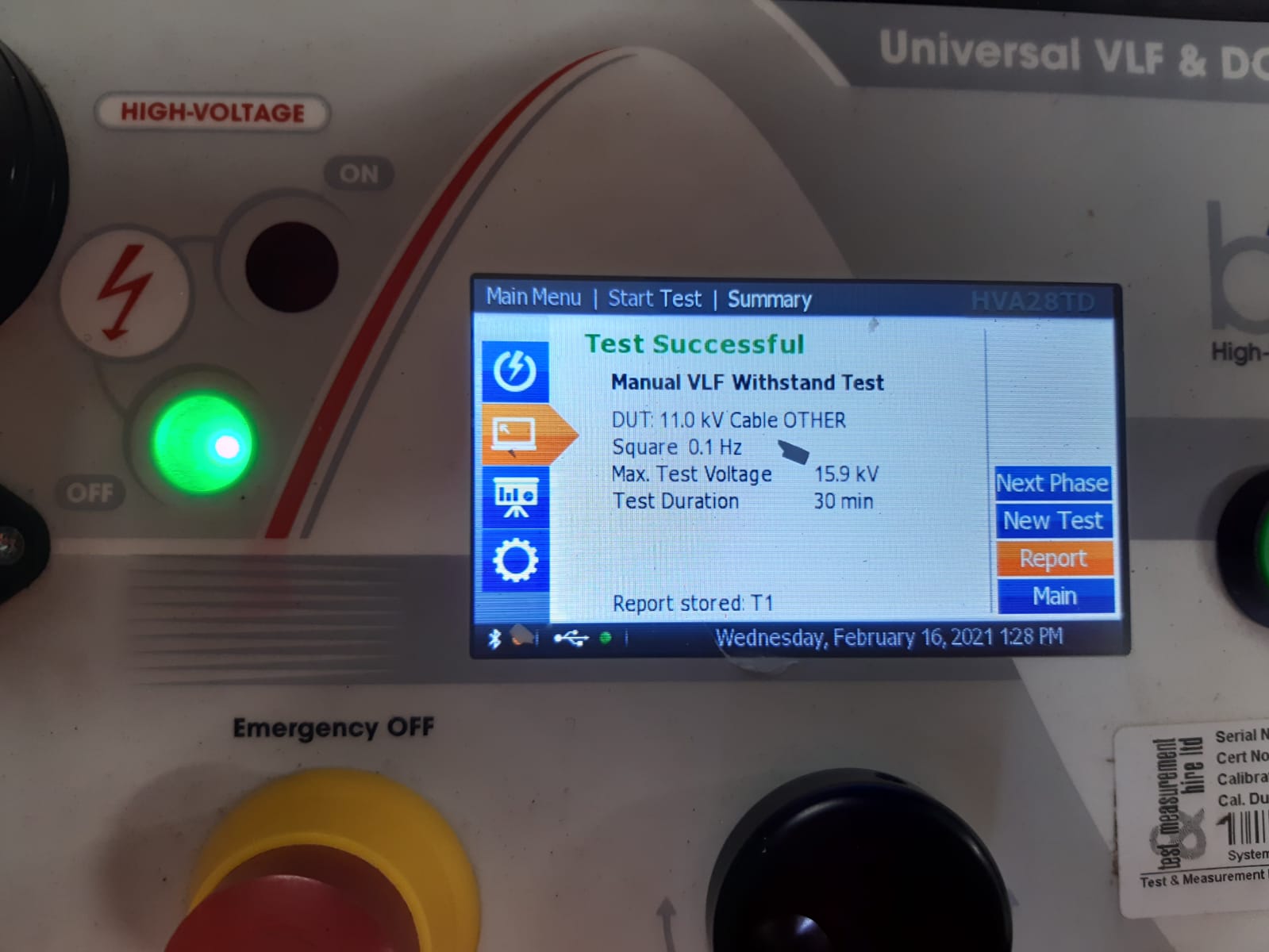

Near Long Itchington, seven kilometres of high voltage cable was laid to enable the energisation of a substation that will power the TBM tunnelling under Long Itchington Wood. Ahead of energisation of the transformers, sheath tests were undertaken. In discussions between the contractor and NEC supervisor, it was agreed that due to bad reception in the area, testing would commence using Teams and then would be remotely videoed and photographed in case of failure.

The first sets of sheath tests were viewed remotely via Teams and the remote inspections failed due to bad signal. It was agreed to continue through WhatsApp. This video inspection was improved, but the tests themselves revealed failures within the cables; two defects were raised as a result. Further fault testing, which was viewed remotely by both Teams and WhatsApp demonstrated that the faults were within several cable joints. These joints were replaced, and the replacement and reinstatement were reviewed via photographic and video evidence in a WhatsApp group set up for discussion, photos and video calls between the contractor, the Subcontractor, the NEC supervisor, the Project Manager and the statutory undertaker and third party asset owner.

Following the replacement of the failed joints, the final pre-commissioning and commissioning tests were undertaken ahead of energisation. This included end-to-end sheath testing of each of the transformers’ cables as well as pressure testing of the HV cables and VLF (very low frequency) withstand test. While one of the sheath tests was able to be viewed live, the VLF withstand test and pressure tests were unable to be viewed live. This was due to a failure of the mobile signal as soon as the contractor entered the switch house. Instead, after a quick discussion with the NEC supervisor of what was required to accurately and thoroughly assure the works, the contractor sent photos and videos of the tests in progress and completed. This allowed the NEC supervisor near instant review of the tests as they were being undertaken.

One of the main outcomes of this series of tests was acknowledging the importance of pre-planning inspections. Despite an ongoing WhatsApp group reviewing daily site progress with joint replacement, preparation for remote witnessing of testing was not properly undertaken. As a result, decisions on how to provide remote witness testing was made on-the-spot to ensure the NEC supervisor was able to witness the tests being undertaken. There was little discussion as to what had to be shown or what data would be gathered. The call was agreed to be undertaken via WhatsApp, as it had been previously shown to be slightly more reliable on that site than Microsoft Teams. When that method of conferencing failed, the backup was a review point. This sufficed for assurance purposes but is not the same as being present for the tests.

Lessons learned and successes

The main successful outcome of using remote inspections, of course, was the ability to continue to assure the works whilst working from home. In addition to limiting site numbers and reducing travel, the remote inspections allowed a NEC supervisor who was classified as clinically extremely vulnerable (CEV) to continue their assurance work witnessing tests and undertaking inspections whilst shielding from Covid-19. In using remote video inspections, the contractor and NEC supervisor were able to develop a new safe method of working, fine-tuning the best ways to capture inspections and tests carried out.

Multiple lessons were learned from this undertaking. These can be categorised as noting what worked and conversely what did not work during remote site inspections. On the plus side, both the contractors and NEC supervisors noted the flexibility of working – a contractor can switch to video whilst on site to quickly review something with a NEC supervisor. As noted by a contractor, a real plus was the ease at which a quick call could be undertaken to review an element of works that the site teams had concerns over. Additionally, trying to find availability of when all necessary parties that may be interested in witnessing a test can be nearly impossible and remote inspections allows parties who may have normally missed a witness point due to a busy schedule the ability to attend. The remote inspections removed the need for the NEC supervisor and other parties to travel and reduced numbers on site during the pandemic. It was also noted by a contractor that if the remote inspection was recorded, it provides proof of inspection and can later be shared to a larger number of people for review, if necessary.

The minuses included the possibility of missing a defect or other anomaly during an inspection due to a bad signal and the constraints imposed by the site itself. If the site is massive and the inspection is not properly run, it is possible that not much can be properly assessed. Additionally, the calls revealed an issue with loss of device signal and running out of battery during inspections. In addition, there’s a site safety aspect – if one is paying attention to recording a video, they are not necessarily paying attention to site movement and works around them. Thus, it is recommended that site works stop whilst the inspection is being undertaken. This is one of the main reasons why mobile phones are not necessarily allowed on site except under certain circumstances. Additionally, weather and site works can cause a cacophony of noise, preventing the site person from hearing the person who is on the other side of the device. It is thought that there may be situations where there may be lighting and signal issues, particularly within confined spaces. Most construction teams have not written a method statement or task briefing for how to safely carry out a remote inspection. Lastly, it was noted by one of the contractors that remote inspections do not provide the camaraderie, communication and level of trust that one develops with regular in-person visits.

From this, recommendations and requirements for a good remote inspection, constraints preventing a good outcome, and possible improvement could be qualified.

Recommendations

For other projects

In undertaking remote inspections on other projects, it is recommended that a meeting be undertaken between the participating parties well in advance of the remote inspection in order to discuss what is to be inspected or tested and what is the best method for viewing those works. Additionally, what fallback measures should be attempted should signal fail, what to do if the inspection needs to be moved to a review point, what data and photos need to be captured in order to provide assurance needs also to be discussed. It is best to have as narrowly defined scope for the inspection as possible, which reduces the possibility of missing a defect. Lastly, as noted above, the ability to record the test or inspection provides assurance to the works.

When starting the inspection, it is good to have a 5-minute briefing with those carrying out any testing and other site operatives to ensure that all are aware of what is being undertaken, what the acceptance criteria is for the testing or inspection being undertaken, and how the assurance for that is captured. Before starting the call, those within camera view should be asked for their consent to film. The device on which the remote inspection is being recorded should be fully charged, with a spare battery and charging cable available. A trial call should be attempted to check signal and to see if there are any impedances to being heard or hearing those on the call. Site works and plant movement in the vicinity of the inspection area or test site should be kept to a minimum for both safety and noise control issues.

To incorporate best practice, using stands, clamps or hands-free worn harnesses on which to hold a phone or 4G-enabled Go-Pro or similar would be ideal. This allows for the engineer to concentrate on site works and the tests that are being carried out. Additionally, it is recommended that the engineer wear earphones or hands-free headset in order to be able to hear others on the call.

For future development

In the future, it is hopeful that more works will be captured via remote inspection, even after the pandemic subsides. It makes sense in highly controlled situations such as factory acceptance tests, as well as small, regular testing such as air tests and mandrel tests. With the addition of improved technology, it is hoped that signals will be robust enough to provide good mobile internet coverage, even in rural areas. Remote inspections can hopefully be expanded to include confined spaces such as deeper sewers and tunnels. It is also hoped that hard to access areas could also be inspected via remote inspection.

Going forward, it is hoped that regular remote inspections provide a value-added method with which to survey ongoing works and provide assurance. It is thought that this may be a way to keep track of site activities over a large geographical area, by participating in multiple site tests and inspections in a single day. Lastly, in an era of lean management, choosing to have a remote inspection may open up the ability for more works to be seen and assessed at a time rather than travelling to remote sites.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to: Gabi Hazelden (HS2 / Jacobs (EDP)), Shaunette Babb (HS2 / Jacobs (EDP)), Maria Andritsou (HS2 / Jacobs (EDP)), Mick Budd (LM / Laing O’Rourke), Diarmaid Ryan (LM / Laing O’Rourke), Chikezie Ibe (CSJV / Costain), Lee Eames (CSJV / Skanska), and Ranvinder Singh (CJSV / Skanska), Arlette Cole (Tideway / Jacobs)