Managing leavers to mitigate the impact to project delivery

After the peak of works, many Costain Skanska joint venture (CSJV) team members were offered roles with follow-on High Speed 2 (HS2) contracts which delivered on career progression and job security. The knowledge and experience gained on the Enabling Works Contract (EWC) made these individuals highly sought after. The impact on CSJV resulted in prematurely losing key resources needed to complete the project.

This paper outlines a behavioural analysis and improvement project that simplified the existing leavers process to manage the transition of team members, increase transparency and minimise impact to the delivery of remaining works.

Background and industry context

The issue of retention of key staff as a project nears completion is common in the industry and will be faced time and time again by the HS2 scheme in the future.

The Enabling Works Contract (EWC) on the southern section of High Speed Two (HS2) phase one includes demolition of buildings within the wider Euston area, utility diversions, environmental and ecological monitoring and a programme of historic environment and archaeological activities, and is delivered by the Costain Skanska joint venture (CSjv).

The EWC South programme of works was geographically spread over Central and West London, and people were leaving the project without having closed out their workload, or the project’s Human Resources (HR) team knowing.

It was common for leavers to operationally report to a Line Manager (LM) who worked for a different Joint Venture (JV) partner, and so the LMs had limited control over the next roles of their team members. This led to local agreements for people to join other projects on a certain date without the completion of a proper review of their workload and whether they had the time to finish, making a complete and proper handover untenable.

As people left early, they were succeeded by people who did not have the operational knowledge of the leaver’s works, which was inefficient and had the potential to add time and cost to the programme.

There were other potential cost implications as a result, given that the project continued to pay for the costs for each person (IT, office, software accesses and sometimes salary) if not notified of the person leaving. These costs had the potential to be disallowed under the contract.

Approach

The CSJV team applied a behavioural science approach, which simplified and improved the leavers process.

An online form was launched which notified operational managers of tasks assigned to individuals. This started a workflow that reviewed the leaver’s succession and plan to close out their responsibilities before their end date was authorised.

This simple and transparent process managed transition and ensured impact to delivery was minimised.

Behavioural science application

In order to mitigate the impact that leavers had on project delivery, the team needed to change the behaviours of individuals involved. To do this, the team conducted a behaviour improvement plan in line with Costain’s Cultural Behavioural Management framework.

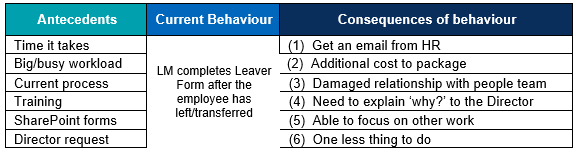

The first step of a behavioural improvement plan is to conduct an analysis that pinpoints particular undesired behaviours, understand what the antecedents are to this behaviour, and review the associated consequences. When the undesired behaviour is fully understood, the consequences that reinforce the undesirable behaviour can be analysed and adjusted.

The pinpointed undesired behaviour in this case was that the LM completes the Leaver Form late, often after the employee has already left or transferred.

Of the consequences listed in Table 1, only (5) and (6) are reinforcing, immediate and definite – the LM in this instance is able to focus on other work and has one thing less to do by completing the form. It is these consequences that are the most impactful in influencing the behaviours. While consequences (1), (2), (3) and (4) are punishing or bad in nature, they all happen later and are unsure. In other words, they might not happen, and because the punishment is not immediate, the consequence has a lesser impact on behaviour.

Costain’s Cultural Behavioural Management programme calls this an Antecedent-Behaviour-Consequence analysis (or ABC analysis). It is structured to guide change in behaviours by doing something different, removing the reinforcing consequences of the undesired behaviour, and introducing new consequences that reward the desired behaviour.

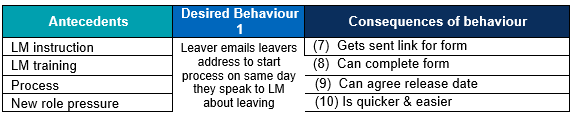

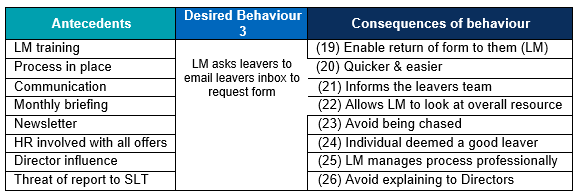

The second step of a behavioural improvement plan is to pinpoint the desired behaviours, understand th new antecedents, and ensure that the consequences of performing these behaviours positively reinforce the person performing them.

Desired Behaviour 1: Leaver notifies the leavers email address to start the process on the same day that they speak to LM about leaving.

By switching the performer from the LM doing the forms late, to the leaver completing the forms as soon as possible to gain authorisation to leave, the consequences listed (7), (8), (9) and (10) are all reinforcing, immediate and definite and therefore likely to succeed.

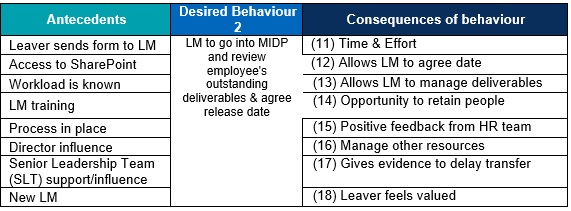

Desired Behaviour 2: LM goes into the Master Information Delivery Plan (abbreviated to MIDP, which is the finite list of all deliverables for project, kept live and on SharePoint), reviews the employee’s outstanding deliverables assigned to them and negotiates a release date based on work that they are yet to complete.

While the punishing consequence of additional time and effort (11) remains, all other consequences listed are reinforcing with (12), (13) and (14) being also immediate and definite.

Desired Behaviour 3: LM asks leavers to email leavers inbox to request form.

The majority of the consequences in Table 4 are reinforcing, immediate and definite and therefore likely to influence the behaviour of the LM, who now only needs to ask the leaver to send a quick email, rather than completing the paper-based forms themselves under the old process.

The third and final step of the behavioural improvement plan was to measure the change in behaviours and introduce shaping steps to better improve outcomes.

Updated leavers process

The updated process flow chart ( Link to chart) developed as a result of the learning gained from the behavioural improvement plan is available as supporting information to this paper. The process considers the antecedents required to trigger the behaviour and the known consequences that positively reinforce it.

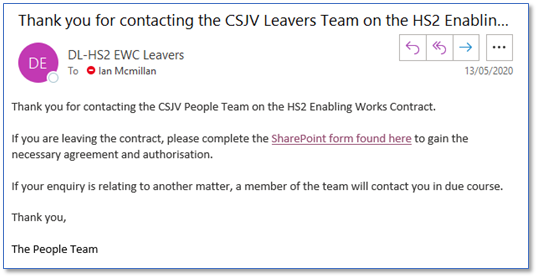

To maximise simplicity in both communicating and carrying out the process, the leaver triggers the process by performing a single action: emailing the dedicated project leavers email address. They will then be sent an automatic reply with a link to the SharePoint form that starts the agreement and authorisation process.

The automatic reply function allows any tweaks made by the HR team in the process’s links or forms to be seamless, as the most current SharePoint link is sent. Also, when analysing the behaviours of leavers, it was acknowledged that leavers are one-time-customers of the process. They will not be keeping tabs on the latest forms, because one only leaves the project once – hence, the simpler the process, the better.

The messaging was therefore basic and singular: if you are leaving the contract, email the EWC leavers email address and follow the automated process that leads from it.

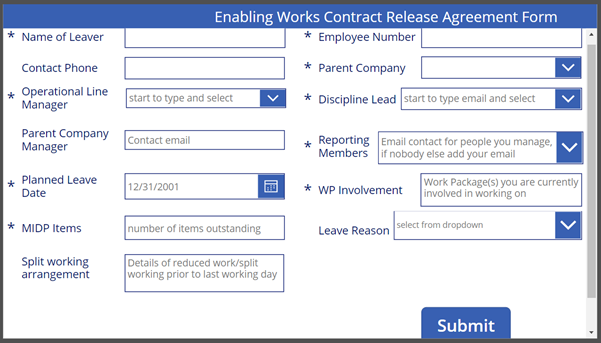

By digitising the tools and forms required to follow the process, further barriers were removed, and automatic prompts were sent to approvers in line with the process flow as the forms were completed.

Tools developed

The programme engaged a Microsoft SharePoint specialist to develop online forms to replace the paper-based system and fully digitise the leavers process.

This tool was linked with the SharePoint MIDPs and project email addresses, allowing automated prompts to ensure timelines were met for leaver authorisations.

Outcomes and learning

The outcome of this initiative was that work packages and LMs had more control over the workload of leavers and were able to negotiate release dates before it was too late, or otherwise mobilise additional resources to succeed the leaver.

The organisation was aware of resource issues far earlier and was able to quickly adapt to maintain delivery service.

The updated process provided complete transparency with the programme’s HR team and allowed better communication of resource gaps and surpluses to ensure efficient delivery, handover and completion of works.

Undetected leavers reduced considerably, and the teams subsequently had far more resilience and control over their workforce.

In 2021, the people team successfully managed a total of 125 people leaving the project, 76% of whom transferred internally to HS2’s follow-on contracts. In the same year the programme successfully completed 34 individual projects. This initiative enabled and supported a year of huge achievement and change.

Recommendations

The following is recommended to others on future enabling projects and programmes of work:

- Large and diverse teams should take the time to pinpoint undesired behaviours and strive to change them to better the outcome.

- Detailed and transparent succession planning is recommended, and key resources that are vital to the handover stages of the project lifecycles should be identified, supported, and retained with well managed expectations between all parties.

- The draw of the next ‘shiny-new’ project or role should not be underestimated by teams. Planned internal moves to other projects are likely to happen more quickly than first anticipated as pressures mount.

- Leavers tend to be prone to optimism-bias over the amount of work promised, but not achieved. By using project-wide tracking tools (in this case the MIDP), the remaining workload is known and understood by the individual leaving and LMs to agree a realistic release date that does not jeopardise delivery.

Conclusion

Future project teams conducting enabling works with high numbers of staff from multiple parent organisations in broad geographical areas are likely to face similar challenges as follow-on contracts mobilise. By looking at behaviours of employees and managers, and changing the antecedents, environment and consequences, this different approach provided control and transparency to ensure teams were suitably resourced.

Acknowledgements

The following people and teams contributed to the development and roll-out of this initiative: Linda Bennett, Kate Young, Lloyd Collins, Ann Marie Cunningham, Emma Scott-Williams, Andy Small, Georgina Lamb and the Costain Cultural Behavioural Management team.