Replacement Floodplain Storage : Linking Engineering and Environmental Design Compatibility

This technical paper provides a summary of the design stage associated with the development of replacement floodplain storage (RFS) and how environmental benefits have been integrated into the design process.

It introduces a novel approach, applicable to future large scale infrastructure projects, for designing RFS that not only alleviates flood risks but also creates environmental habitats and wetland features to move towards No Net Loss in biodiversity. This innovative concept adapts the conventional RFS design that often overlooks ecological enhancements.

This paper showcases a transformative strategy that harnesses Building Information Modelling (BIM), integrating flood risk management with the creation of habitats, working toward No Net Loss in biodiversity at a route-wide level.

This forward-thinking methodology represents a significant advancement from traditional planning approaches, embodying the integration of engineering and environment to deliver the best outcomes of both and will be of use to those working on major infrastructure projects in the future.

Background and industry context

To comply with National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF)[1], Environment Agency and best practice design of replacement floodplain storage (RFS) detailed in CIRIA C624[2], new developments must ‘create space for flooding to occur by restoring functional floodplain’. The HS2 technical standards and Environmental Statement (ES)[3] outline the requirements for protecting and enhancing the environment, with a requirement that ‘No Net Loss’ in biodiversity is achieved. HS2’s Blue Infrastructure Design Approach[4] also emphasises the importance of an integrated design approach around existing watercourses or other bodies of water. This approach aims to deliver multiple outcomes beyond the primary water supply, flooding and water quality considerations. The HS2 Flood Risk Technical Standard[5] underpins the design development of HS2.

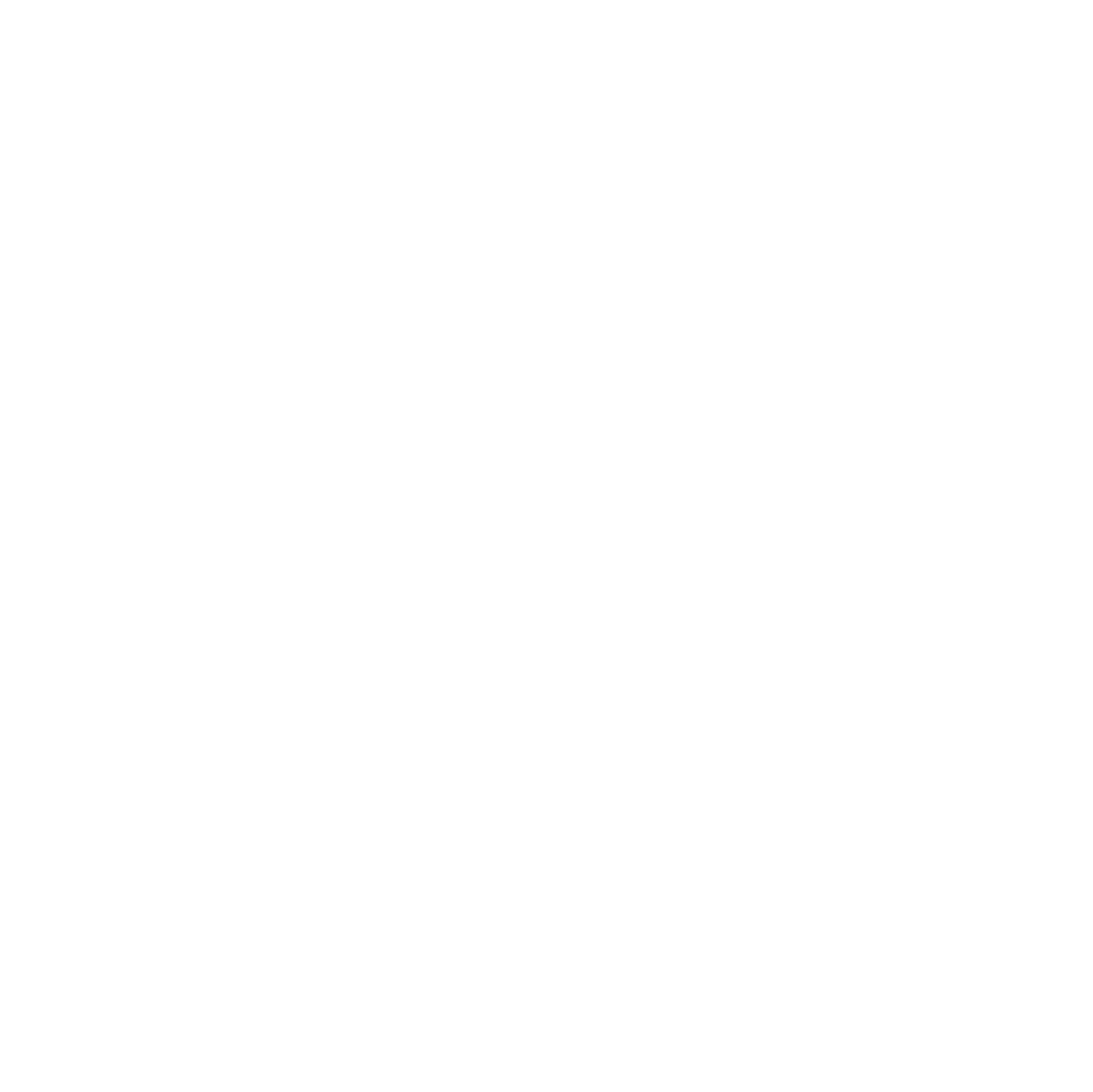

Best practice replacement floodplain storage (RFS) design involves calculating the total volume of HS2 works in the floodplain up to the flood level associated to the 1 in 100-year return period, including an allowance for climate change. This is referred to as displaced flood volume. The displaced flood volume is then split into 200mm elevation bandings. To mitigate potential increases in water level and flood risk, the displaced flood volumes at each banding must be offset within the floodplain to ensure the storage fills at the same rate that it would have done under existing conditions. Figure 1 presents an illustration of direct RFS design. This approach aligns with the requirement of CIRIA C624[2], which is adopted by the EA as best practice. Demonstrating compliance with the technical standards and CIRIA C624 is essential for achieving development consent.

Figure 1: Illustration of direct replacement of flood storage

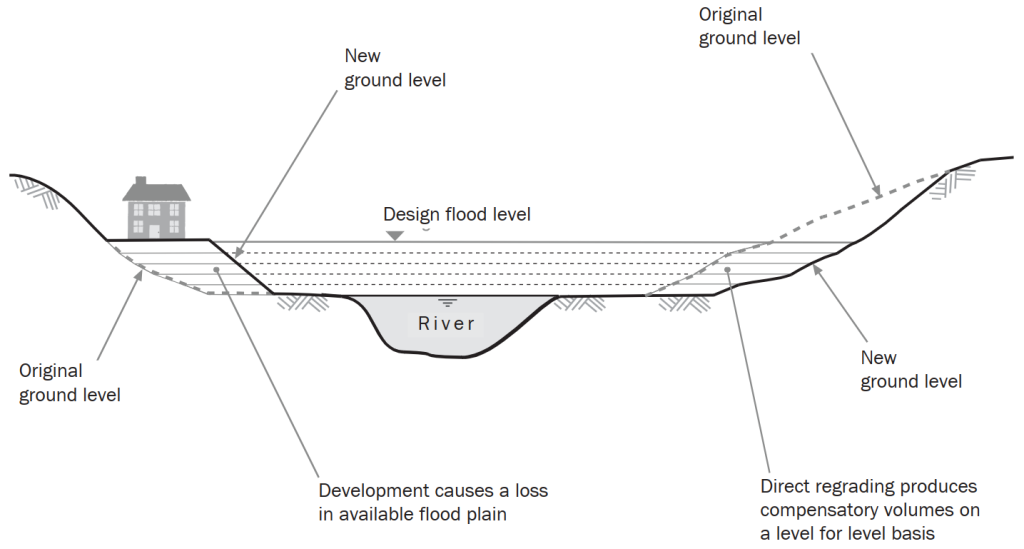

Reports, such as the ‘Achieving more: operational flood storage areas and biodiversity’[6]) established that solutions benefitting the environment the most, often provide poor flood storage solutions (as summarised in Figure 2). For example, afforesting an RFS would interfere with its functionality. Conversely, an RFS with no environmental mitigation would be a detriment to the environment due to the large land take, environmental disruption, as well as the missed opportunity to achieve environmental targets.

Figure 2: Flood Benefit versus Biodiversity

This technical paper outlines the successes of achieving, whilst working within project constraints, the balance between engineering and the environment . It is presented as part of the Main Works Civils Contract (MWCC) for the northern section of High Speed Two (HS2) Phase One including Long Itchington Wood Green Tunnel to Delta Junction and Birmingham Spur and the Delta Junction to the West Coast Main Line (WCML) tie-in, being delivered by the BBV Integrated Project Team which includes Mott McDonald

Approach

HS2 Phase One is committed to achieving No Net Loss in biodiversity at a route-wide level, implementing the mitigation hierarchy which aims to avoid first, before mitigating and compensating for habitat loss, in seeking to minimise the impacts of the scheme on biodiversity. This process has been driven by collaborative working between the engineering design and environmental teams and has been informed by the consultation and engagement process associated with the ES[4], with key stakeholders including the Environment Agency, Natural England and Local Wildlife Trusts.

Where possible, the scheme has been designed to avoid impacts on sensitive ecological receptors which include protected and notable species and habitats. However, owing to the scale of the HS2 scheme, there are locations in which ecological impacts cannot be reasonably avoided or mitigated against, in which case compensation in the form of habitat creation can be proposed. Combining RFS with environmental features both contributes to No Net Loss through high-distinctiveness habitat creation, and offsets planning losses within the habitat.

The extent of habitat mitigation and compensation included within detailed design has been determined through application of professional judgement at a site-specific level, rather than through the use of a biodiversity offsetting metric or other loss-to-gain ratios. Instead, biodiversity metric calculations have been used as a means of quantifying progress towards the overall goal of achieving route-wide biodiversity No Net Loss. This has taken extensive management and coordination between design teams, environment teams, and relevant stakeholders such as the Environment Agency and Lead Local Flood Authorities (LLFAs).

Innovation in Replacement Floodplain Storage Function and Design

By design, RFS often requires a large amount of land, either as a single large area or several smaller areas. Innovation has been integral to the interdisciplinary design development of RFS to increase accuracy in calculating storage volumes, prevent over-digging and optimize the RFS design in terms of area, location, and land use.

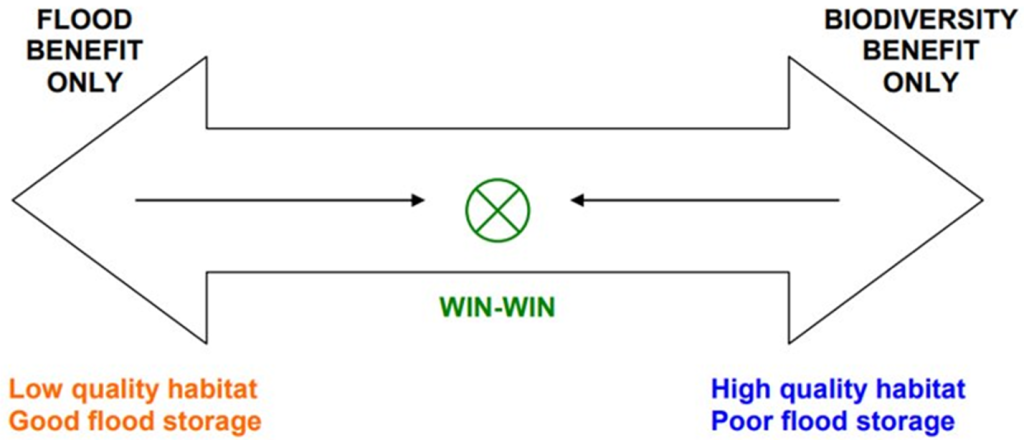

A streamlined BIM process, illustrated in Error! Reference source not found. utilising, 3D LiDAR combined with 3D scheme models created a full awareness of all existing and proposed constraints. This allowed the RFS designs to find all available opportunities and de-risk issues prior to the construction phase.

Figure 3: Representation of initial stage of BIM process to calculate displacement volumes

- Obtain a combined asset BIM model, known as the federated model and cut to the shape of the hydraulic flood plain extents.

- Combine the topographic LiDAR data and extract the lowest and highest asset elevation, representing the upper and lower RFS levels.

- Undertake BIM model processing to extrude asset surfaces and calculate the volume of new infrastructure within the flood plain. Analyse this data across 200mm level bands.

- Identify suitable locations for RFS considering volume and level constraints.

- At the 200mm level band calculate RFS volumes. Compare each level band against the volume to offset and ensure they are equal or bigger.

- Review the RFS design against other design constrains before finalising the solution.

This streamlined RFS design process has enabled environmental benefits to be realised such as:

- RFS offers large bodies of water in which riparian habitat (wetlands adjacent to rivers and other waterbodies) can be created and existing habitats enhanced.

- a series of smaller excavations that minimise the potential for negative environmental impacts that require offsetting elsewhere;

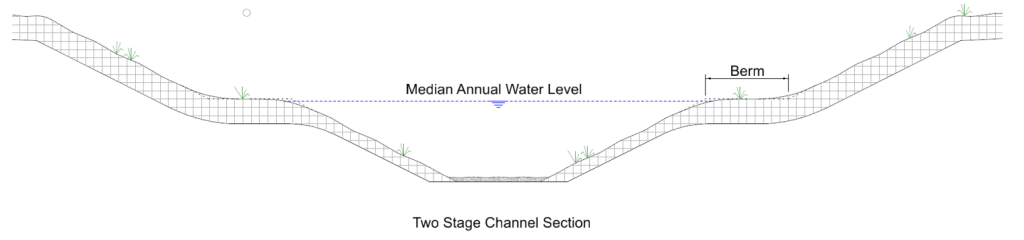

- modifying river morphology to create depth variations lends itself to wetland planting and creation. For example Berms (Figure 4) that widen of the river cross section at levels above median annual water level (2 yr Annual Exceedance Probability), and Scrapes that lower the ground adjacent to the river, can contribute towards aquatic habitat creation, support WFD objectives and contribute to RFS volume.

Figure 4: Typical Two-Stage Channel with Berm

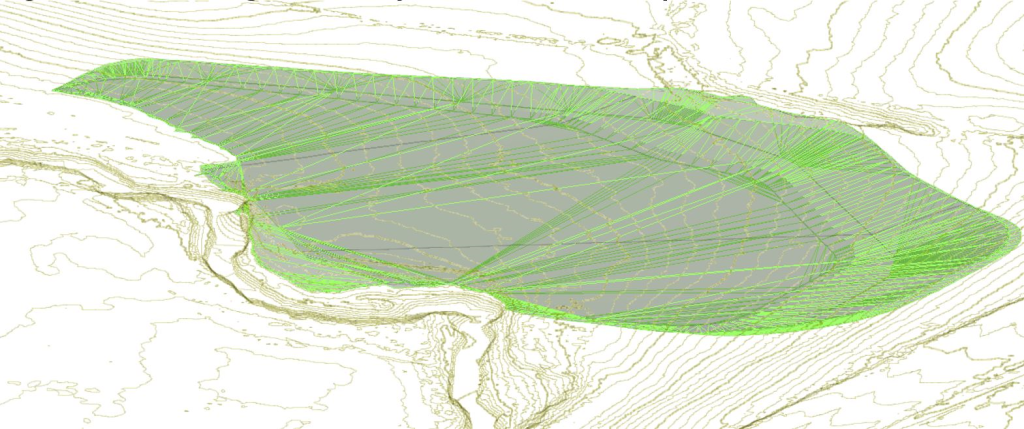

This approach has been implemented at HS2 sites including Canley, Finham and Balsall Common RFS. Figure 5 is a representation of initial space proofing of an RFS following the volumetric analysis, which enables the excavation of sufficient volumes at each banding.

Figure 5: Initial design for Canley Brook Viaduct RFS prior to wetland features being added

With further refining in BIM, the RFS can be made more attuned to the surrounding topography and environment for example with the incorporation of wetland features. BIM analysis also helps to develop novel landscaped RFS solutions in constrained spaces between HS2 assets and can often reduce volumes at the bandings most challenging to find space in the floodplain. Refining the RFS lessens the societal impact of HS2 by reducing the need to acquire additional land of local landowners.

Innovation in Habitat Creation within RFS

Wetlands Creation

A typical RFS design can require a large amount of land to construct, and thus result in a large amount of habitat loss. Wetland creation within the RFS has been proposed, providing a nature-based solution to flood risk management, whilst positively contributing to HS2’s No Net Loss target. Wet grassland planting along realigned watercourses and within floodplains creates a diverse and connected habitat, encouraging a range of protected and notable species to pass through, forage and breed.

Figure 6: Example of Canley Brook Viaduct RFS and integrated ecological features in detailed design.

Further ecological enhancements to Canley Brook Viaduct RFS have involved the inclusion of ditches and scrapes within areas of wetland creation, shown in Figure 6 above.

Scrapes are shallow excavations which hold rain or flood water seasonally, staying damp for the majority of the year. Scrapes within wetland create a heterogenous habitat with a variety of vegetation structure and varying water levels, which contribute to wildflower-rich grasslands with a diverse invertebrate population. Large, shallow scrapes also provide valuable habitat to wading birds, amphibians and riparian mammals.

Once fully established (Figure 7) and under correct maintenance and monitoring, wet grassland planting will produce lowland meadow – a Habitat of Principal Importance, as defined under Section 41 of the Natural Environment and Rural Communities (NERC) Act 2006 (6). This habitat forms an important part of the foodchain by providing the primary feeding resource for nectar feeding invertebrates, as well as supporting biodiversity along watercourses. The wet grassland provides ancillary habitats to the aquatic habitats within the wider landscape which contain riparian species such as otter and water vole. Implementing this design will have a significant contribution to the HS2 Green Corridor Strategy [7]

Figure 7: Initial design for Canley Brook Viaduct RFS prior to wetland features being added

Opportunities to create floodplain grazing marsh, a UK Biodiversity Action Plan (UKBAP) Priority Habitat, as defined by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee[8], have also been explored, which often compliments RFS design owing to its resilience to regular flood events.

UKBAP Priority Habitats are the most threatened and requiring conservation. This habitat comprises periodically inundated pasture or meadow with ditches or other features, and is particularly important for breeding waders and internationally important populations of wintering wildfowl, and support rich varieties of plant and invertebrate species[9]. Maintenance of grazing marshes typically involves low level grazing by livestock to achieve a varied, tussocky sward structure, whilst in turn creating microhabitats for invertebrates through trampling. This can provide landowners with the opportunity to continue their farming practices within the area following the completion of the scheme.

Tree Planting/Afforestation

There is generally a reluctance for incorporating tree planting into RFS design due to a loss of flood flow conveyance and storage volume. However, tree planting can connect adjacent woodland habitats and linear features, supporting the HS2 Green Corridor Prospectus[10] which aims to create a network of bigger, better-connected, climate resilient habitats. Tree planting is proposed along the realigned Canley Brook, adjacent to the RFS (see Figure 6).

The following considerations were taken into account through close collaboration between the environment team, flood modelling team, and river engineering team:

- The reduced storage capacity owing to the physical size of the plants. The volume of each tree (mature tree volume) is calculated to determine the reduction in floodplain capacity and RFS volume adjusted if necessary.

- A slower flow, caused by trees in the floodplain increasing roughness, could result in increased sedimentation, raising the floodplain level and reducing the effectiveness of the RFS. As such, the RFS were designed to be above the median annual water levels so the main sediment conveyance would remain in the channel.

- Debris from loss of leaves and branches should also be considered, as this could locally raise the ground over time. Other vegetation may grow around the trees further contributing to debris deposit, and there is a possibility of trees falling over, resulting in an increase in volume loss.

- Consideration of whether the location of the tree planting area would pose a health and safety risk whereby if trees became dislodged there would be a risk of blockage of an existing culvert or river control structure.

It is important to plant a range of native tree species that are suitable to the local climate and habitat type (e.g. alder, willow, hawthorn, hazel, birch, rowan), and are more resilient to persistent flooding scenarios.

Flood-resilient species such as hawthorn and rowan were selected and located along the realigned Canley Brook at 8m intervals, to maintain a key commuting route of importance for bats, which was identified within the ES. The proposed feature trees create a linear habitat which will guide bats along the brook and encourage them to forage around the RFS, where invertebrate populations will thrive as a result of the wetland habitat creation.

Towards achieving No Net Loss at route-wide level

HS2 is committed to being a highly sustainable and climate resilient railway, delivering no net loss to biodiversity on a route-wide scale. Biodiversity metric calculations were undertaken at the commencement of the scheme; these used available baseline information to calculate the number of biodiversity units generated by the habitats present within the land required for Phase One prior to construction and provide a comparison to the biodiversity units that will be present post-construction following habitat creation or enhancement.

The results in relation to grasslands are positive, route-wide, and suggest the habitat creation measures proposed will achieve a clear ‘trading up’ in the distinctiveness of created habitats, with an increase in the total number of biodiversity units generated by grassland. A higher proportion of these units will be generated by habitats of ‘high distinctiveness’ (i.e. those that would qualify as habitat of principal importance). Wetland habitat creation integrated within RFS design will help to contribute to this ‘trading up’ of habitats. Baseline habitats across the HS2 trace predominantly consist of low distinctiveness grassland or arable fields; RFS have been situated within these habitats and subsequently, higher distinctiveness habitats such as lowland meadow can be planted to achieve a better result post-construction than the initial baseline.

The overall increase from RFS represents 14.35 Biodiversity units representing 1.23% of our current No Net Loss deficit and full calculations and methodology are detailed within the No net loss in biodiversity calculation – methodology and results document [11].

In relation to watercourses, calculations predict a gain in watercourse biodiversity upon completion of the scheme. This result largely reflects the fact that the scheme will, in many cases, create a more meandering and diverse channel than is currently present. Wetland integration within RFS, such as shown in Error! Reference source not found., will further contribute to this increase in both watercourse biodiversity and increasing habitat distinctiveness, ensuring that flood risk management converges seamlessly with habitat creation to achieve Biodiversity Net Gain and working toward No Net Loss in biodiversity on a route-wide scale.

Outcomes

The creation of wetland habitats in conjunction with the requirements for RFS show how innovative thinking can bring engineering and environmental requirements together. The key environmental outcome of this method is the positive contribution towards HS2’s No Net Loss objectives. Initial calculations indicate that grassland habitat creation represents an overall gain in biodiversity units across the scheme, which will be further bolstered by the introduction of wetland creation within RFS design.

The innovative use of BIM to efficiently locate storage volumes has been utilised during HS2 delivery, meeting the goals set to mitigate flood risk linked to the proposed HS2 scheme including a consideration for climate change. Over-digging has been minimised while maximising the use of available space.

Integrating habitat creation with RFS construction across the HS2 scheme presents a highly effective nature-based solution to alleviating flood risks, providing benefits for both flood risk management and the environment.

Flood storage areas across the UK are already making an important contribution to national Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP) targets, however a high proportion of these areas support ‘lower value’ biodiversity (7). The approach to wetland creation within RFS design that we have followed allows low distinctiveness habitats such as low maintenance grassland and arable field, which are common choices for RFS locations across the scheme, to be replaced with high distinctiveness Habitats of Principal Importance and in some cases UK Priority Habitats, representing a significant positive gain for biodiversity and leaving a legacy which contributes positively to these environmental targets.

Guidance was provided to landowners regarding RFS at the ES Stage of HS2, indicating that RFS would be returned to agriculture, with the RFS suitable for grazing as stated in the Basis of Design document for RFS [12]. The habitat creation approach followed allows land to be returned to landowners to continue their farming practices involving livestock, but also offers an enhanced, natural approach to the maintenance of grazing marsh habitats, in which livestock are a key component.

Learnings and Recommendations

BIM and multidisciplinary collaboration

Collaborating between design teams that have assets in the floodplain is crucial. This collaboration allows for accounting of design changes that may arise, impacting RFS size and location. Effective communication plays a key role in ensuring that proposed changes from other disciplines are comprehended. BIM serves as the ideal interface or presentation tool, facilitating clear understanding among design teams regarding the location of RFS and how their proposed alterations might impact this. This clear communication fosters a cohesive approach to managing floodplain assets.

Landownership

The habitat creation approach HS2 has followed allows land to be returned to landowners to continue their farming practices involving livestock but also offers an enhanced, natural approach to the maintenance of grazing marsh habitats, in which livestock are a key component.

Recommendations for the future projects are to seek greater opportunities for wider environmental enhancement during negotiating land purchase. Certainly, as climate change impacts are felt in the UK, increasingly larger areas of land will need to be purchased for RFS.

RFS design standards

HS2 Technical standards dictate the base slope of the RFS is no less than 1 in 100. However, this would preclude the creation of wetland habitats, which require a relatively flat base. However, an enhanced maintenance strategy for the wetland and to avoid siltation needs development (discussed below).

Groundwater interaction

Another factor required in the creation of sustainable wetlands is high groundwater level. Initially this was seen as a significant technical challenge due to risks associated with interfering with the groundwater level in the area. There were concerns about potentially creating a change to flows within local watercourses and drawdown of the groundwater table. Undesirable flow paths and rutting could occur, posing issues for future land use. However, with the introduction of wetlands at several sites, the high groundwater level has proven to be key in providing enhancement and demonstrating that it’s better to work with the natural environment than against it.

Maintenance of conventional RFS

During both the design and consenting processes, maintenance was discussed with relevant stakeholders. As there is no specific guidance on maintenance of RFS outlined in best practice or technical standards, it was understood that RFS should be treated as floodplain, allowing it to develop with natural river process. RFS is designed to mimic nature and should be treated as any other part of the floodplain. However, designs typically include additional storage to allow for a degree of silt buildup.

It is not always feasible to maintain an RFS as they are very large areas that would be environmentally invasive to dredge with any regularity. RFS should be designed to be self-sustaining whereby siltation/deposition processes are considered from the outset. Care should always be taken to ensure low or zero maintenance options are provided.

Maintenance of RFS with wetlands

Learning outcomes for RFS design improvements or environmental targets can conflict with regulators/consenting bodies. For example, shallow gradient or flat bases should be assessed for siltation risk and if a maintenance strategy may be appropriate. Siltation can also reduce the capacity of RFS or potentially introduce levels of silt beyond tolerance for wetland habitats.

The benefit of providing RFS volumes with wetlands to contribute to No Net Loss targets can conflict with standards for protection of aquatic habitats. Prior to determining the RFS design approach liaison with stakeholders and the regulator should be undertaken to understand any aquatic ecological constraints are relevant to the area. There is the potential for wetland scrapes to provide substantial ecological benefit but a post flood event review should be conducted to assess the risk of damage to wildlife (e.g. fish entrapment) to make sure there is an overall benefit versus risk.

Planting/Afforestation in RFS

In the guidance report ‘Vegetation in Replacement Floodplain Storage’[13] we have developed a systematic approach to facilitate the design of planting vegetation on the RFS.

Planting an RFS comes with several considerations, owing to the following effects:

- Planting will reduce the storage capacity of the RFS owing to the physical size of the plants, and potentially from long term debris accumulation.

- Planting will increase the ‘roughness’ of the floodplain. By their nature, RFS are close to the watercourse and increasing roughness could slow the flow and increase flood water levels.

While native species are preferred, where RFS capacity is constrained or there are health and safety concerns with debris, poplar trees are recommended owing to their fast-growing nature, resilience to waterlogged condition and ability to be cropped in future. Poplar typically grow in a uniform fashion with little variance in trunk diameter, which also contributes to simpler RFS volume calculations.

Conclusion

The synergy between engineering and the environment is key to the success of the achieving goals set in the local and national planning policy and HS2 technical standards, whilst contributing to HS2s No Net Loss targets.

The use of BIM has enabled an efficient calculation and placement of the RFS to minimise the impact on the environment as much as possible whilst achieving the strict flood risk target set out in the HS2 technical standards.

RFS design utilising relatively flat base gradients and consideration of groundwater level represent an opportunity for ecological habitat creation in the form of wetland habitat, afforested areas, scrapes and pastures. Geomorphological designs i.e. widened channels counted in RFS volumes has created aquatic habitats, while maintaining a typical daily flow regime. However, particular attention must be given to the environmental risks of the area, particularly of the impact of an RFS to the aquatic environment. Additionally, critical to approval of wetland and non standard RFS by the regulator is a strategic maintenance considerations, for its life-cycle.

The close collaboration with the environment teams has allowed these wetland habitats to be designed and optimised, whilst the quantifiable environmental benefits have been able to work towards No Net Loss.

With the opportunities for meeting UK Biodiversity Action Plan targets for wetland habitats, being limited to those areas where sufficient water resources are available, the potential importance of RFS to contribute must not be overlooked. Further, the sympathetic development of RFS to provide water storage and biodiversity where wetlands would naturally occur, may reduce long term maintenance and works with the natural catchment processes, rather than imposing something that is less sustainable.

Acknowledgements

- Balfour Beatty Vinci

- Mott MacDonald – HS2 Environmental Discipline Team

- Mott MacDonald – HS2 Rivers Discipline Team

References

- Department for Communities and Local Government. Technical Guidance to the National Planning Policy Framework. 2012. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-planning-policy-framework-technical-guidance

- Construction Industry Research and Information Association (CIRIA). C624 Development and Flood Risk – Guidance for the Construction Industry. 2004. Available from: https://www.ciria.org/ItemDetail?iProductCode=C624

- High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. London West Midlands Environmental Statement Non-Technical Summary. 2013. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/69739/hs2_london_wm_env_statement_non_technical_summary.pdf

- High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. Blue Infrastructure Design Approach. 2013.

- High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. Flood Risk Technical Standards (HS2-HS2-EV-STD-000-000011). 2013.

- UK Government. Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act. 2006. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/16/contents

- Environmental Agency. Achieving More: Operational Flood Storage Areas and Biodiversity. 2009. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/291695/scho0309bpux-e-e.pdf

- Joint Nature Conservation Committee. UK Biodiversity Action Plan Priority Habitat Descriptions – Coastal and Floodplain Grazing Marsh. 2016. Available from: https://data.jncc.gov.uk/data/1df9b775-1475-46c7-8507-33e7503c370f/UKBAP-PriorityHabitatDescriptions-Rev-2016.pdf

- Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC). UK BAP List of Priority Habitats – Coastal and Floodplain Grazing Marsh. 2008. Available from: https://data.jncc.gov.uk/data/1df9b775-1475-46c7-8507-33e7503c370f/UKBAP-PriorityHabitatDescriptions-Rev-2016.pdf

- High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. Green Corridor Prospectus. 2020. Available from: https://www.hs2.org.uk/documents/green-corridor-prospectus/

- Department for Transport. HS2 London to West Midlands – No Net Loss in Biodiversity Calculation – Methodology and Results. 2015. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/509268/HS2_London_to_West_Midlands_no_net_loss_in_biodiversity.pdf

- Balfour Beaty Vinci. Detailed Design – Basis of Design – Replacement Floodplain Storage (1MC08-BBV_MSD-EV-REP-N001-100039). 2023.

- Balfour Beaty Vinci. Vegetation in Replacement Floodplain Storage Guidance Report (1MC08-BBV_MSD-EV-REP-N000-100072). 2023.