Technical evidence for a non-technical audience

This paper shares experience of technical evidence production as part of the High Speed Two (HS2) Phase 2a project, which led to successful outcomes for the Promoter at House of Commons Select Committee petition hearings. The learning and observations contained within will be relevant to any projects implementing hybrid Bills but also more generally by any project where it is necessary to present technical information to a non-technical audience.

It begins with a summary of the hybrid Bill and petitioning process. It then explains the role of the Select Committee of MPs or Lords who, as a non-technical audience, act in a quasi-judicial role and pass judgements on matters where the Promoter (Secretary of State for Transport, with High Speed Two Ltd acting on his behalf) and a Petitioner (an objector to the proposed scheme) cannot reach agreement.

Two examples from the Phase 2a hybrid Bill are chosen to illustrate the process; petitions in favour of a 6.4km-long tunnel between the villages of Whitmore and Madeley, and a petition to underground a 7.8km-long electricity supply connection providing traction power to the railway. Both issues were heard before the House of Commons Select Committee, with the Committee, in both cases, finding in favour of the Promoter’s position.

The key recommendation is that early engagement with prospective Petitioners is imperative. This provides the opportunity to share evidence defending the proposed scheme in a more informal setting than at a Select Committee hearing. Petitioners’ proposed alternatives to the scheme must be explored in detail, and the findings must be shared with them in an accessible way and in a timely manner. Legal counsel and expert witnesses should also be well briefed in advance of petition hearings. Evidence slides for Committee hearings need to be clear and concise, while sketches and diagrams can be useful visual aids.

Introduction

The journey of High Speed Two (HS2) Phase 2a through Parliament began with the deposit of the High Speed Rail (West Midlands to Crewe) Bill in July 2017 [1]. This Bill, once enacted, authorises works to construct and operate the railway, compulsory purchase of land and property rights, and a wide range of ancillary activities, such as interference with highways and utilities. It will also grant development consent (deemed planning permission) and disapply other existing legislation. This process has been previously described in detail by Podkolinski [2]. Deposit of the Bill to Parliament followed route consultation and refinement dating back to 2012.

The mechanism for promoting this legislation is a hybrid Bill; it is a hybrid of a public bill, which affects the general public, and a private bill, which affects individuals or organisations in a specific way. Hybrid Bills are relatively rare and are typically used on large infrastructure projects such as the Channel Tunnel (1987), Severn Bridge (1992) and Crossrail (2008).

There are several benefits to using a hybrid Bill rather than an alternative consenting approach such as a Development Consent Order. It shows Government support for the project, the principle of the scheme is established early (at Second Reading of the Bill in the House of Commons), it allows for amendments to existing legislation or creation of bespoke legislation, and changes may be introduced during the process. The main downsides are that it requires use of scarce Parliamentary time and is subject to the Parliamentary calendar, leaving open the possibility of delays to the project. This could be caused by events such as a general election or higher priorities on the Government’s agenda.

Bill deposit comprises the Bill itself, plans and sections, an estimate of expense, a book of reference (a register of land, property, and the respective owners and occupiers affected by the Bill), and other supporting documentation including an Environmental Statement. This triggers First Reading of the Bill in the House of Commons, which is a procedural step before consultation on the Environmental Statement begins. Following this is Second Reading in the House of Commons. This involves debate and, if required, a vote. If passed, the principle of the scheme is set. For Phase 2a, the vote at Second Reading passed by a wide margin of 295 votes to 12 and demonstrated strong cross-party support for the project. Once the Bill passes Second Reading, this initiates a period known as ‘petitioning’.

Petitioning

Where an individual or organisation’s property or interests are ‘specially or directly affected’ by the proposed scheme, they have the right to object (‘petition’) to a Select Committee of Members of Parliament (MPs). This Committee consists of members unconnected to the project and reflects the make-up of the House, in the case of Phase 2a comprising three Conservative Party MPs and two from the Labour Party.

The Committee acts in a quasi-judicial role, hearing evidence from both the Petitioner and the Promoter on the matters of concern, before determining what action, if any, should be taken (the Secretary of State for Transport is the Promoter of the Bill, with High Speed Two Ltd acting on his behalf). Petitioning issues can range from concerns about construction traffic routes or the use of agricultural land for environmental mitigation purposes, to requests for tunnels or other major route alignment changes.

Once the petition hearings have been completed the Select Committee publish their verdicts in a report [3] [4] [5] and the Bill moves to a Public Bill Committee stage. It then returns to the floor of the House of Commons for Report/Third Reading, before moving to the House of Lords where the process repeats along similar lines. Petitions to the House of Lords are heard in front of a new Select Committee and Petitioners can petition both Houses.

Inherent risks of the petitioning process for both the Promoter and the Petitioner are that the Committee finds in favour of the other’s argument or that a solution is prescribed that neither party is happy with. In order to avoid these risks, many petitioning issues can be resolved in advance of Select Committee hearings. This is typically done by way of an assurance. This is a unilateral written commitment from the Promoter that the contractor (‘Nominated Undertaker’) must comply with. In these cases, the Promoter and Petitioner will seek a mutually beneficial solution for both parties, which is then entered on a register [6] that becomes final upon Royal Assent of the Bill.

Assurances attempt to reduce as much uncertainty as possible for Petitioners without unduly constraining the detailed designers and construction contractors. This flexibility is important in order to deliver the scheme in a timely, economic manner. Examples of assurances could be committing to relocate drainage ponds to facilitate easier movement of agricultural vehicles or avoiding the use of construction traffic routes at school pick-up and drop-off times.

The issues that tend to be heard in front of the Select Committee are therefore those on which no common ground can be reached between the Promoter and Petitioner. Typically, these issues would involve the need for significant additional expenditure or would (in the Promoter’s view) place undue constraint on the contractor. In some instances, it may be that both parties simply agree to disagree about the scale of the impact or the ability to comply with the project’s Environmental Minimum Requirements. The Committee’s role then becomes that of a neutral observer who hears the evidence in front of them and decides on an appropriate outcome.

The onus rests on the Promoter to justify its proposals in the face of challenge from a Petitioner. It could be reasonably expected that, in the absence of a strong defence for the Promoter’s proposals, the Committee would find in favour of the Petitioner’s arguments. This therefore requires the collation and presentation of technical evidence, the preparation of which is the subject of this paper.

Preparation of Evidence

Stakeholder Meetings and Verbal Evidence

Evidence used to defend the scheme against challenge can take many forms and can be presented in many fora; conversations, emails, letters, meeting minutes, reports, sketches, maps, for example. Defending the proposed scheme does not begin at Select Committee hearings with evidence bundles but at a one-to-one level with stakeholders, often over a period of months and years. As referenced above, Select Committee hearings are ultimately an opportunity for both parties to opine on issues where no agreement can be found.

Ideally, petitions and those who submit them should not come as a surprise to the Promoter. The Promoter should be keenly aware of those who are affected by the proposed scheme and have made every effort to engage with those individuals or organisations before ever getting to the petitioning stage of the process.

It can be relatively straightforward to identify private landowners and larger organisations, such as county, borough, district, or even parish councils, who are directly impacted along the line of route. However, it may be more challenging to identify individuals with general concerns about noise or dust or, for example, those concerned about the stopping-up of a public right of way or an increase in construction traffic past their property.

Once stakeholders who may be impacted are identified, it is important for the Promoter to discuss possible concerns with them. This is usually a face-to-face meeting in a council office, a land agent’s office, a village hall or an individual’s home. These settings, and the face-to-face communication style, allow for a less formal interaction and a more open dialogue on issues of concern. Having a competent, suitably prepared team who are capable of clearly articulating the Promoter’s position is the first step in providing evidence to successfully defend challenges to the proposed scheme.

Examples of typical engineering-related conversations in these meetings may be questions regarding drainage ponds and the potential for their removal, relocation or reshaping. The engineer present should be prepared with information such as the relevant drainage catchment area, direction of flow, outfall locations, any assumptions regarding attenuation or infiltration, and any constraints such as culverts or other track crossings. In terms of environmental concerns, for example environmental mitigation planting, it is important to know the function of proposed planting (either landscape, ecological or both), any relevant survey information and relevant receptors to be able to defend the design when it is challenged. This is important in order to be able to credibly answer questions from the stakeholder, to provide evidence for the design rationale and to compare that rationale against any potential alternatives that may be proposed.

These verbal communications with stakeholders, along with accompanying sketches or marked-up plans that might be used to aid discussions, are an underrated and possibly overlooked step as the first piece of evidence that a prospective Petitioner will see or hear from the Promoter defending the proposed scheme. They are also very useful for reducing the number of areas for disagreement between both parties; where the Petitioner accepts the points raised by the Promoter, this reduces the number of arguments that need to be heard in front of the Committee. This portrays both parties in a good light to the Committee as it demonstrates a willingness to work together to reach an understanding on points of contention.

Promoter’s Response Document (PRD) and Petitioner Assurance Letter (PAL)

In the period between submitting a petition and the petition hearing itself, a Petitioner should receive at least two formal communications from the Promoter.

The Promoter’s Response Document (PRD) will typically be the first formal communication that a Petitioner will receive from the Promoter following the submission of a petition. Aiming for an issue date no later than four weeks in advance of a hearing, the PRD responds to every point raised within the petition. Signposting to the available information, such as policy papers or the relevant section of the Environmental Statement, is an important first step. This is particularly true where there has been little to no engagement prior to petitioning, or for those who are unfamiliar with the layout of the documents, which can be overwhelming. The PRD may also provide a brief summary of a petitioning point being discussed during previous engagement. Where the request is new, it may outline that further engagement will be required to reach a resolution.

No later than two weeks in advance of the petition hearing, a follow up document, known as a Petitioner Assurance Letter (PAL), will be issued. This aims to summarise where agreement has been reached between the Petitioner and the Promoter and where assurances (formal commitments) have been offered. It will also set out the Promoter’s position on the points where agreement has not been reached.

Both documents can be used as evidence by either party during the petition hearings to support their arguments. They should be written in plain English to make them as accessible as possible. The primary target of the letters is the recipient, but they will also be read by the Committee members. If the documents are unnecessarily complex in the use of language or do not properly respond to the petition, it will be obvious to the Committee. In that instance, they may be more sympathetic to the Petitioner’s arguments than the Promoter’s.

Evidence Bundle

No later than two business days in advance of a Select Committee hearing, both the Promoter and Petitioner can submit evidence that they would like to use during the hearing. The Promoter’s evidence bundle would typically include the above-mentioned documents, location maps showing the proposed works relative to the Petitioner’s landholding or administrative area, and a series of evidence slides addressing specific points in the petition.

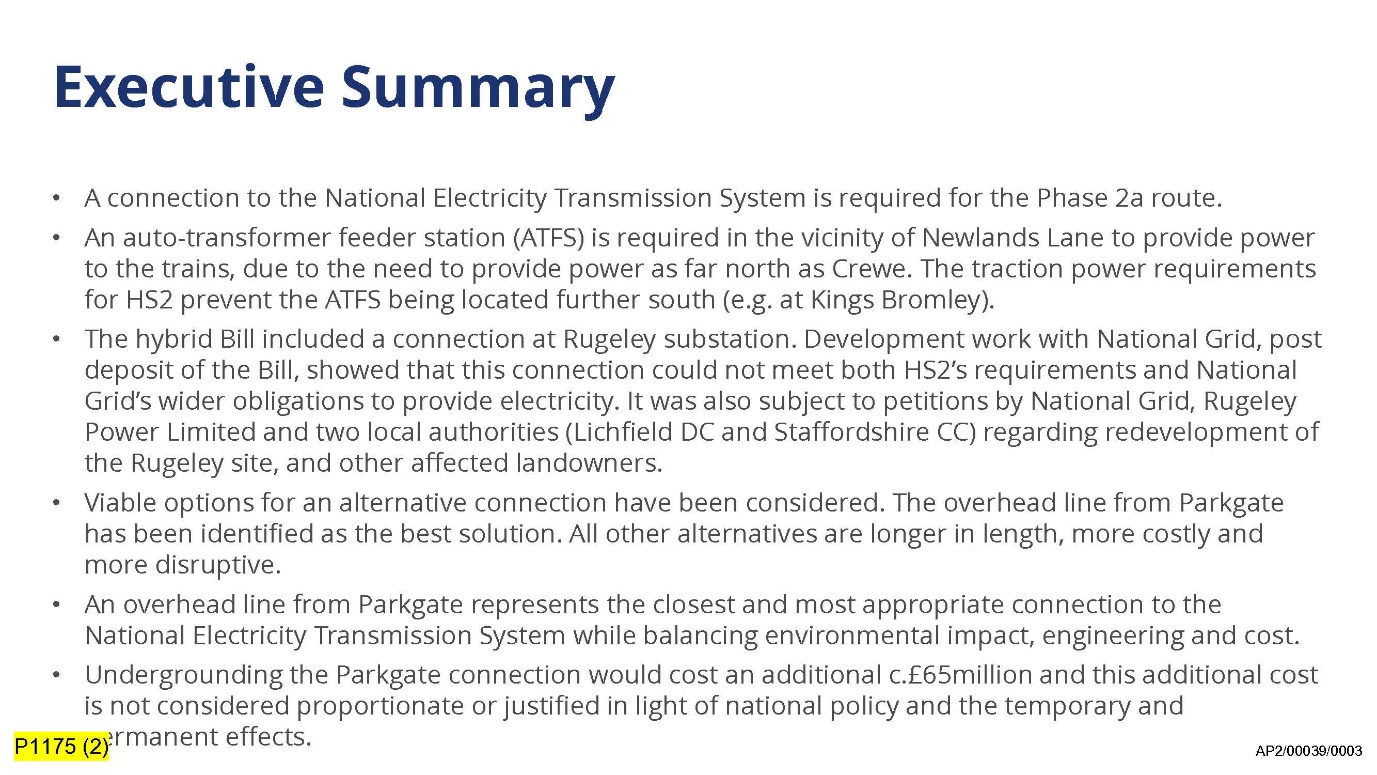

These evidence slides should address the petitioning point with the key facts of the Promoter’s case that will make the most impact on the Committee – those charged with finding a resolution between the competing arguments. Where possible, a marked-up snapshot of a drawing or a sketch / illustration brings further clarity to the points being made. Example evidence slides are shown below in Figure 2 and Figure 3. These show how months of detailed technical work, engagement and preparation need to be condensed to a series of bullet points or sketches, which neatly and succinctly capture the vital points of an argument.

Legal Counsel and Witnesses

At petition hearings, the Promoter is represented by legal counsel, often with support from expert witnesses for topics such as noise and vibration or land compensation. These individuals argue the Promoter’s case and respond to questioning from the Committee. The credibility of counsel and witnesses relies on them being able to speak confidently and eloquently, with evidence to support any points or arguments they make. This necessitates thorough preparation in advance of any hearings, including appropriate briefing on the case at hand by those who have had prior engagement with the Petitioner. Counsel and witnesses would be expected to rely on their professional knowledge and experience to respond to questions around general matters, policies, or ways of working.

Often questions arise during hearings that cannot be answered without some further technical analysis or consultation with other parties. In those instances, a note would be submitted to the clerk of the Committee in the days following the hearing. The Committee would then be able to consider this additional detail alongside the evidence they heard before publishing their findings. Examples of these follow-up submissions can be seen on the Select Committee website. [9] [10]

Technical Analysis

Where a Petitioner proposes an alternative to the scheme as it is designed, it needs to be developed to a similar level as the hybrid Bill design so that its relative merits and demerits can be properly assessed and explained. This is also part of demonstrating the HS2 Ltd value of respect and the desire to leave a positive legacy for the life of the project. [11]

Two examples will be used to illustrate the process at the most extreme end of the spectrum. These potential scheme changes, arising from stakeholder engagement, would have necessitated a substantial change to the powers contained within the Bill, a significant change in environmental impact and a large increase in cost.

Whitmore to Madeley Tunnel

The Phase 2a scheme, as deposited to Parliament, contained two tunnels at Whitmore and Madeley, approximately 1.2km and 1km in length respectively. As part of the reasonable alternatives described in the Environmental Statement, one alternative option was a single 6.4km-long tunnel to replace the two tunnels in the Bill scheme. This single tunnel was reported as being significantly less complex to construct and would have had several environmental benefits; avoidance of property demolition, reduced loss of agricultural land, reduction in isolation and traffic impacts, reduction in visual impacts and avoidance of impacts on watercourses. However, this single tunnel was also significantly more expensive to construct and operate due to the increased tunnelling length, based on the information available at the time. [12]

Engagement with stakeholders in the affected communities identified a desire to adopt this single tunnel option. The onus was therefore on HS2 Ltd, on behalf of the Promoter, to substantiate the cost differential and evidence the judgement of the costs outweighing any engineering or environmental benefits. The single tunnel option was therefore developed to a ‘concept design’, detailed enough to fully appraise its impact and present a fair comparative analysis of the two options. The appraisal considered a wider range of technical disciplines than was evaluated prior to Bill deposit, including tunnel ventilation, traction power design, temporary power supplies, utility diversions, shaft construction and construction traffic.

The findings of the comparative analysis were published in a report in March 2018 [13], prior to Select Committee hearings on the tunnel beginning in April 2018. It determined that the single tunnel would be, in engineering terms, a ‘major worsening’ when compared to the two-tunnel scheme. Conversely, it reported that the single tunnel scheme would be a ‘major environmental improvement’. The full engineering and environmental comparison matrices, as well as the comparison matrices from prior to Bill deposit, were published as appendices to the report. This transparency helped to support the Promoter’s position.

Whilst the Promoter and Petitioner agreed on the environmental merits of the single tunnel, they disagreed over the costs. The report therefore contained a dedicated chapter about the cost assumptions, such as tunnelling rate and disposal of surplus excavated material. A detailed cost breakdown was provided in an appendix to the report. Unsurprisingly, costs became the key topic of discussion during the subsequent Select Committee hearing [14] with the Petitioners calling an expert witness who presented their own costings to the Committee. [15]

The key lesson learned from this exercise is that transparency is crucial, particularly where cost information is integral to the argument and subject to scrutiny by the Select Committee. Additionally, the timing of the publication of key pieces of evidence needs to be carefully considered. This report was published in March 2018, approximately five weeks in advance of the Select Committee hearing. This allowed the target audience a fair opportunity to review it, as opposed to, for example, publishing it as part of an evidence bundle two working days before the hearing.

Following the petition hearing, the Select Committee found in favour of the Promoter’s two-tunnel scheme, stating in their first special report, “The Committee has made an “in principle” decision to reject petitioners’ preferences to put the whole Whitmore to Madeley Heath section in tunnel (the single tunnel)…the proposal for the single tunnel is a costly option and the Committee would like to see an undertaking from HS2 to direct its resources instead toward improvements for the local and wider community.” [3]

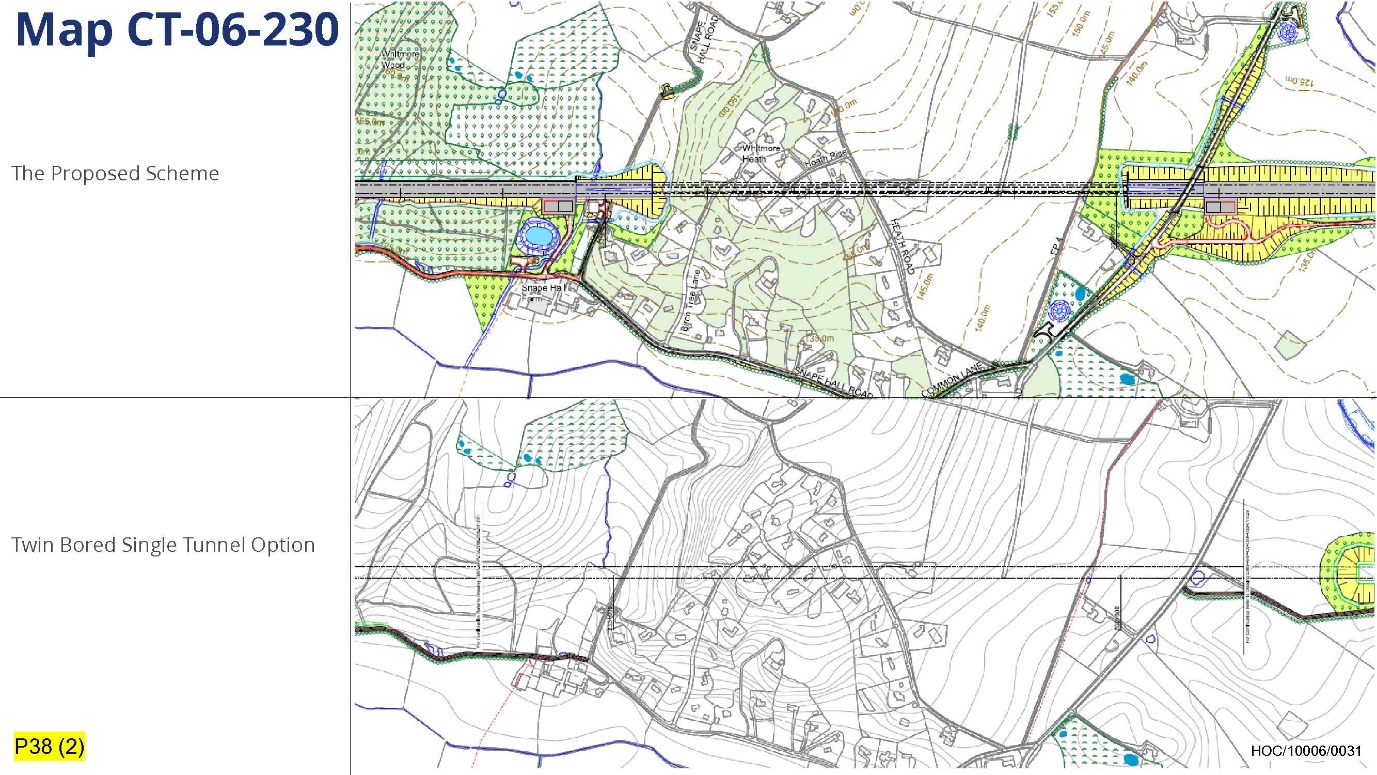

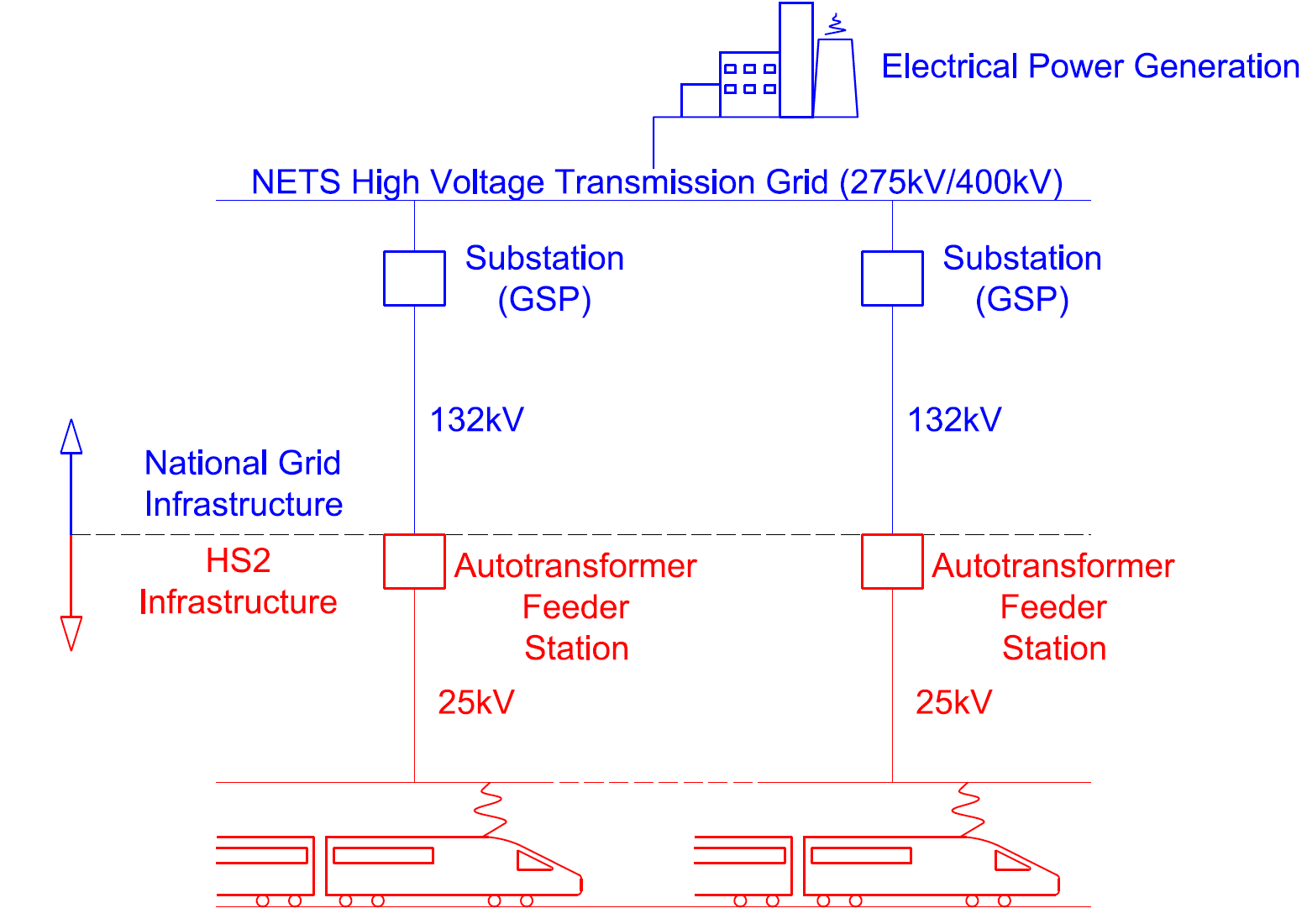

Grid Supply Point Connection at Parkgate

Following deposit of the Phase 2a hybrid Bill, further design development work was carried out regarding the traction power supply. This showed that, for National Grid to meet HS2’s power supply requirements for Phase 2a whilst maintaining resilient supply to the local area, additional physical power supply infrastructure would be needed. The original grid supply point was at an existing substation, approximately 4km west of the Phase 2a route. The further development work demonstrated the need to relocate the grid supply point to a new substation at Parkgate, approximately 8km east of the route. This change to the scheme was brought forward via Additional Provision 2 (AP2) to the Phase 2a Bill, which was deposited to Parliament in February 2019.

Engagement regarding this change began in September 2018 with a face-to-face meeting with three affected parish councils. This was followed in October 2018 by a public information event attended by over 200 people from the local community. Given that the AP2 proposal was for three electrical circuits, carried on two parallel 7.7km rows of pylons ranging between 23m and 38m high, it was a significant change.

A report was therefore commissioned, which attempted to simply, coherently and logically explain the trail of events that resulted in the change, for people to read and digest in their own time. It addressed key recurring themes arising from the previous engagement meetings and events:

- the requirements of the traction power system for the railway;

- development of the hybrid Bill proposals;

- design development following Bill deposit;

- alternative options that were considered;

- the choice of the AP2 option.

Graphics were used to clearly explain key themes and concepts, such as the role of National Grid and where the boundaries of responsibility between National Grid and HS2 Ltd lay (Figure 4). The report was also written in plain English, which was vitally important given that the House of Commons Select Committee’s second special report had specifically cited accessibility of HS2 Ltd documents as an area of concern. [4]

The report, entitled ‘Grid Supply Point Connection at Parkgate’ [16], was published in February 2019 on the same day that AP2 was deposited to Parliament. The timing of publication meant that the background information in the report could be read alongside the full environmental impact assessment of the change.

It became clear during engagement that the parish councils were going to petition the House of Commons Select Committee, seeking to replace the pylons and overhead lines with underground cables. This was not an issue where agreement would be reached between the Promoter and the Petitioner as the underground option was likely to require significant additional expenditure. It was therefore incumbent on HS2 Ltd to produce evidence for the petition hearings, which illustrated a fair comparative analysis of an above-ground and underground option alongside the costs of each option, so that the Committee could make an informed decision on the matter. This evidence primarily took the form of a second report, published as an addendum to the first report described above. [17] This second report needed to both satisfy the stakeholders that their concerns had been heeded, investigated, and analysed thoroughly, and uphold scrutiny by the Select Committee.

For the AP2 Environmental Statement, the proposed traction power connection’s environmental impact was assessed across a 200m-wide corridor, including an assumption that all ecological habitats within that corridor would be lost during construction. It also incorporated an assessment of the visual impacts of the tower (pylon) locations. This represented the reasonable worst-case environmental impact assessment but gave an unrealistic view of what the above-ground connection was likely to be in practice. Adopting a similar methodology for an equivalent underground connection would not have adequately illustrated the differences between the two alternative schemes.

The second report therefore described a refined version of the AP2 scheme using a 65m-wide corridor. The same 65m-wide corridor was then used to fit a comparative underground alternative scheme, enabling a fair comparison. Both indicative schemes needed to be advanced to a level of preliminary design in order to adequately appraise their impacts and generate a fair cost comparison. Collaboration with National Grid was also necessary to ensure that assumptions were accurate and in line with their work practices. For transparency, the entire engineering and environmental comparison matrices were published as appendices to the report.

The key lesson from this experience is to allow adequate time to undertake the detailed analysis and produce supporting drawings and documentation. The petitioning period for AP2 closed at the end of February 2019, with the relevant petitions being heard towards the end of April 2019. Had the Promoter waited until after the petition had been submitted before commissioning the necessary evidence, there would have been insufficient time available to undertake the work. It is therefore vitally important to carry out early engagement with likely Petitioners to identify key issues and have the time to investigate them to the level required for a Select Committee hearing.

Following the petition hearing, the Select Committee again found in favour of the Promoter’s above-ground scheme, with their third special report stating, “We accept that the proposal in AP2 for the siting of overground pylons between Parkgate and the Newland Auto Transformer Feeder station contained in AP2 is the best option for provision of electricity to the railway.” [5]

There have been instances where the Select Committee have not found in favour of the Promoter’s position, and lessons can also be learnt from these cases. One example of this was a parish council who petitioned to replace a T-junction with a roundabout, citing improved access/egress to and from the village of Swynnerton with additional traffic calming benefits past a nearby property. The Select Committee ultimately ruled in favour of the petitioner stating “HS2 Ltd should build a roundabout where the diverted Tittensor Road meets the A51” [4].

While some high-level differences between the two options were presented, the topic received more attention from the Select Committee than the Promoter had anticipated, and the Promoter was underprepared. There were site-specific issues that needed to be explained with thorough technical detail in relation to traffic capacity and potential impacts on pedestrians, cyclists and equestrians. In this case, the expert witness and legal counsel had not been thoroughly briefed and prepared to address the differences between a roundabout and a T-junction at this location. This left them unable to fully defend the Promoter’s position when questioned by the Select Committee members.

Additionally, the Petitioner’s roundabout alternative had not been developed in enough detail by the Promoter to properly explain the differences between the two schemes. After developing the alternative, it emerged that the roundabout option required the diversion of a high pressure gas pipeline, construction of an additional retaining wall, provision of an balancing pond and maintenance access, increased amount of highway construction works on the A51 and additional land, both temporarily and permanently, from an adjacent holding. Had these details been available at the Select Committee hearing, it may have influenced the Select Committee’s decision towards retaining the original T-junction as proposed by the Promoter.

Conclusions and lessons learned

Experience suggests that winning the favour of the Select Committee can be achieved by working collaboratively with Petitioners, treating their objections to the scheme respectfully, working these suggestions through to a level where they can be fairly assessed, and finally (assuming that the outcome of the appraisal supports this) presenting how the proposed scheme remains, on balance, the most appropriate course of action.

Early engagement with prospective Petitioners is key to gaining an early understanding of their concerns. This provides time to explore potential scheme alternatives in the necessary detail as this can be a lengthy process, as has been evidenced in the two examples described in this paper. Additionally, engagement meetings with prospective Petitioners are often the first opportunity that Petitioners will have to see sketches and hear explanations from technical specialists defending the proposed scheme.

Transparency is important; where details supporting decision-making are available, such as costs or sift reports, it should be considered that they be shared with stakeholders. This ensures there can be no accusations of hiding pertinent information. However, the timing of publication of evidential reports needs to be carefully considered. While evidence for Select Committee hearings only needs to be provided two working days in advance, Petitioners and the Committee members themselves need time to be able to consider and digest what is provided.

For evidence slides to be used in Committee, the text needs to be clear and concise, and succinctly capture the key points of the arguments. Sketches, diagrams and annotated maps can be useful tools to illustrate concepts to both Petitioners and the Select Committee.

Letters and other correspondence with Petitioners should be as accessible as possible for ease of understanding by all parties. Finally, legal counsel and witnesses need to be properly briefed before appearances at Select Committee hearings and correspondingly supported during hearings by those who best know the details of the case.

These conclusions and lessons learned are based on experiences on HS2 Phase 2a but can be easily applied to further phases of the project, particularly on the upcoming Phase 2b western leg Bill. Many of these observations could also be applied to other projects, settings or scenarios where it is necessary to present technical information to a non-technical audience.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge the support of Professional Services Contractors, Arup, WSP, and their supply chains, who were vital to producing much of the material used throughout, from engagement meetings through to petition hearings. Additionally, the author wishes to acknowledge the many colleagues across HS2 Ltd and National Grid who have attended meetings and produced, reviewed and shared evidence at all stages of the Phase 2a Select Committee process.

References

| Title of References | |

|---|---|

|

[1] | UK Parliament, “Bill stages — High Speed Rail (West Midlands – Crewe) Bill 2017-19 to 2019-21”, 17 July 2017. [Online]. Available: . [Accessed 15 April 2020]. |

|

[2] | J. Podkolinski, “HS2 railway, UK – the hybrid Bill”, Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Transport, 2018. |

|

[3] |

Authority of House of Commons, “House of Commons High Speed Rail (West Midlands to Crewe) Bill Select Committee First Special Report of Session 2017-2019”. |

|

[4] |

Authority of House of Commons, “House of Commons High Speed Rail (West Midlands to Crewe) Bill Select Committee Second Special Report of Session 2017-2019”. |

|

[5] |

Authority of House of Commons, “House of Commons High Speed Rail (West Midlands to Crewe) Bill Select Committee Third Special Report of Session 2017-2019”. |

|

[6] | UK Government, “HS2 Phase 2a register of undertakings and assurances”, 2 February 2018. [Online]. [Accessed 15 April 2020]. |

|

[7] | High Speed Two Ltd, “Promoter Evidence P1175 (24 April 2019) Grid Supply Point Connection at Parkgate”, 24 April 2019. [Online]. [Accessed 11 May 2020]. |

|

[8] | High Speed Two Ltd, “Promoter Evidence (24th April 2018)”, 18 January 2019. [Online]. [Accessed 01 June 2020]. |

|

[9] | UK Parliament, “HS2 to Committee Power supply/running of trains”, (14 May 2019), 22 May 2019. [Online]. [Accessed 15 May 2020]. |

|

[10] | UK Parliament, “National Grid to Committee Corrections to Oral Evidence”, (14 May 2019), 22 May 2019. [Online]. [Accessed 15 May 2020]. |

|

[11] | High Speed Two Ltd, “Our principles and values”, 19 March 2018. [Online]. [Accessed 23 April 2020]. |

|

[12] |

High Speed Two Ltd, “High Speed Rail (West Midlands to Crewe) Environmental Statement Volume 2 Community Area Report CA4: Whitmore Heath to Madeley,” 2017. |

|

[13] |

High Speed Two Ltd, “HS2 Phase 2a: Whitmore Heath to Madeley Tunnel Report,” 2018. |

|

[14] | UK Parliament, “Petitioner Evidence – Petitions 130, 108, 141 and 187 (23rd April 2018) (Afternoon),” 24 April 2018. [Online]. [Accessed 04 June 2020]. |

|

[15] | UK Parliament, “Petitioner Evidence – Petition 130 (23rd April 2018),” 09 April 2018. [Online]. [Accessed 04 June 2020]. |

|

[16] |

High Speed Two Ltd, “Parkgate Report: Grid Supply Point Connection,” 2019. |

|

[17] |

High Speed Two Ltd, “HS2 Phase 2a Select Committee: Grid Supply Point Connection at Parkgate – Addendum,” 2019. |

Peer review

- Michael Court, Historic Environment LeadHS2 Ltd